Scientist of the Day - Johann Gottfried Zinn

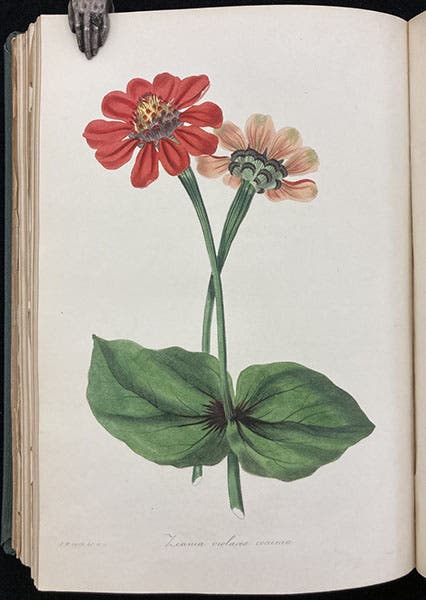

Johann Gottfried Zinn, a German botanist and anatomist, was born Dec. 4, 1727. He studied at the University of Göttingen, where Albrecht von Haller was reforming medical research, and where in 1736 he had established a botanical garden, much as Linnaeus had just done in Uppsala. In 1753, young Zinn, all of 26 years of age, became director of the botanical garden and a professor of medicine at the University. He apparently worked to introduce foreign species of plants into the garden. It is said that he planted some seeds sent to him by the Germann envoy to Mexico, which produced not dahlias, but a spindly pale red flower that the Mexicans called mal de ojos, or "eyesore." We don't know if any of this is true. What is certain is that Linnaeus later named the plant Zinnia peruviana after the German gardener. I have yet to find out exactly when or where Linnaeus did this, and it makes a difference, because Zinn died on Apr. 6, 1759, only 31 years old, and he may never have known that it would be through this plant that his name would come down to us.

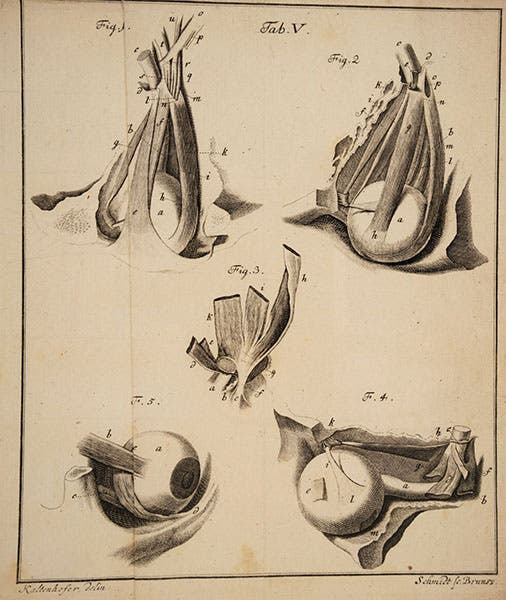

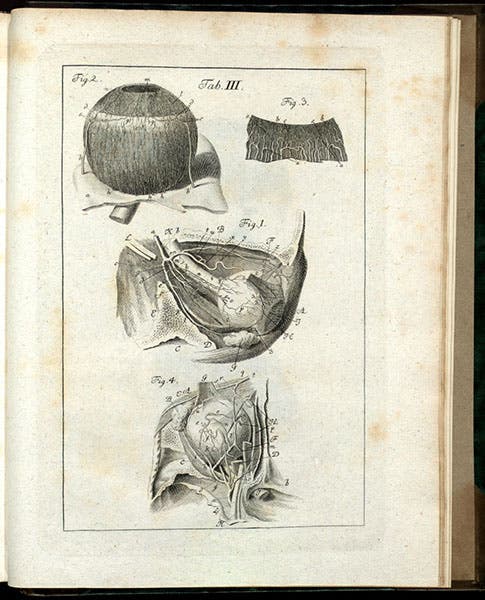

In addition to running the Göttingen botanical garden, Zinn also pursued his anatomical studies of the human eye, which he had undertaken for his dissertation under Haller, and in 1755, he published a book, Descriptio anatomica oculi humani. I confess that I had never seen or even heard of this book before researching this post, and I found a copy of the 1780 edition partially on line at the Thomas Fischer Library at the University of Toronto, and another, the first edition of 1755, in the Wellcome Collection in London, and I must say I was flabbergasted by the 7 engravings included in the book, which are outstanding in their detail, especially the ones showing the muscles that move the eye. We show here an engraving from the 1755 edition in the Wellcome Collection, and another from the 1780 edition in Toronto (third and fourth images). You can see all 7 plates at once on this University of Toronto Library webpage.

These engravings were drawn by Joel Paul Kaltenhofer, whom I did know, for he engraved the moon map for Tobias Mayer, a Göttingen astronomer, who also died young, in 1762, and whose map we featured in our Face of the Moon exhibition – you can see the map here. The scientists in Göttingen were lucky to have at their call the services of Kaltenhofer, whose drawings/engravings in both cases are exquisite.

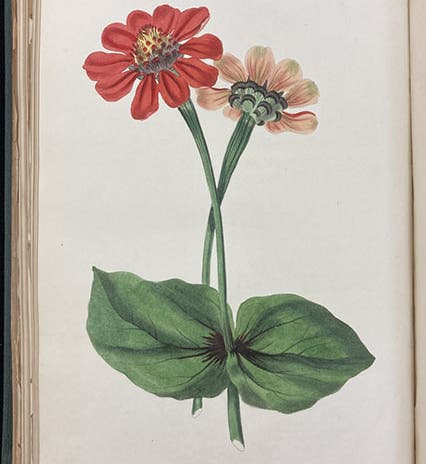

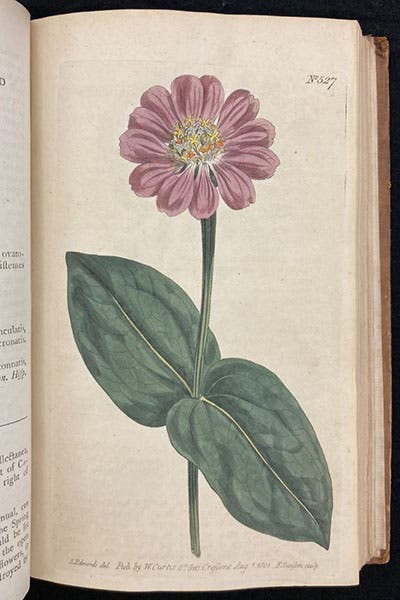

Getting back to zinnias, as garden plants, they were slow taking off in Europe, and one can hardly find mention of them in the various illustrated botanical magazines that began to flourish in the nineteenth century. I did find two (but only two) hand-colored engravings among the thousands that appeared in Curtis's Botanical Magazine, in 1801 (fifth image) and 1820. There was also one in the very first volume of Paxton's Magazine of Botany, 1834, that depicted the purplish species that was introduced to Europe around 1800 and which is a bit showier (first image). But there was little sign in the 19th century that the zinnia would become a garden staple in the 20th century.

Zinnias recently came into the news when Scott Kelly, an American astronaut on board the International Space Staton (ISS), released on Twitter on Jan. 16, 2016, a photograph of a plant that he had just brought to flower on the ISS. It was a beautiful (if gravitationally confused) zinnia (sixth image). Kelly claimed it was the first flower grown from seed in space, but he later learned that he had been preempted. Still, it was a beautiful sight, and Zinn would no doubt have been proud of his namesake’s success.

Just as the folks in Uppsala have preserved the Linnaeus botanical garden as it was in Linnaeus’s day, so too has the University of Göttingen, which keeps its Alter Botanischer Garten much the way Zinn left it, too abruptly, in 1759 (seventh image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.