Scientist of the Day - Johann Kiessling

On Aug. 27, 1883, the volcano on the island of Krakatoa, between Java and Sumatra, after spitting lava for several months, exploded catastrophically, releasing more energy than any natural event since the eruption of Tambora in 1815. Tens of thousands of people were killed, and Kraktoa itself nearly disappeared as a geographical entity.

The first scholarly reaction by geologists was a book by a Dutchman, Rogier Verbeek, 1885, called Krakatau (the Dutch spelling of the volcano), with dramatic lithographs of the explosion. We do not have Verbeek's book, but we wrote a post on him anyway.

The Royal Society of London then sponsored a commemorative volume, containing a smorgasbord of papers on the eruption by a variety of experts, and including some beautiful colored lithographs of the red sunrises and sunsets that were common for several years after the explosion, even in England. It was called: The Eruption of Krakatoa, and Subsequent Phenomena: Report of the Krakatoa Committee of the Royal Society (1888). We do own this book, and we included several of its plates in our post on Verbeek, as we did in a post on Edward Munch, whose painting The Scream is thought to depict a sky reminiscent of the Krakatoa era of Munch's youth.

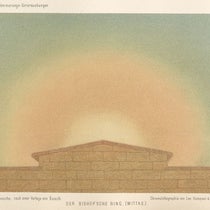

Today we offer a glimpse of a third book on the atmospheric aftermath of the eruption of Krakatoa, the most beautiful of the three, but one rarely drawn on in the frequent articles and books on Krakatoa, perhaps because it is so scarce. It was written by Johann Kiessling, a German physicist who wanted to know exactly how an eruption of material in Indonesia could cause the atmospheric effects he saw in Hamburg, where he taught at the Johanneum. By doing experiments in his lab, effectively inventing the cloud chamber, he was able to show that the colors of Krakatoan skies were not caused by refraction, as in a rainbow, but by diffraction, which causes interference fringes in light. His book was called (translating from the German): Investigations into Twilight Phenomena to Explain the Atmospheric-Optical Perturbations Observed after the Krakatoa Eruption (1888), and we have a copy in our history of science collections. It has unfortunately been rebound in red buckram, but the nine plates within are in pristine condition, and oh! are they gorgeous!

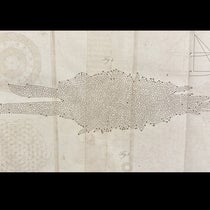

The plates are chromolithographs, meaning they were printed in color from multiple lithographic stones. The prints reproduce "aquarelles" (watercolors) by Eduard Pechuėl-Loesche, an accomplished landscape painter who deserves an entry of his own, and will get one someday. The prints derive much of their impact from the fact that they were printed on thick pebble-grained paper, and then cut out and mounted on sheets that were bound into the book. The combination of the grain of the paper, the grain of the lithographic stone, and the colors of the inks, results in incredibly rich prints, which must be seen in person to be appreciated, although I tried to convey some sense of the texture with two details, our ultimate and antepenultimate images here.

Kiessling's explanations of atmospheric optics were apparently accurate and were accepted by others working in the field, and it has been shown that when C.T.R. Wilson invented his cloud chamber for detecting cosmic rays and other atomic particles, he explicitly acknowledged Kiessling's contribution.

Why, do you suppose, did this man who was so conscious of the power of images, not leave behind a portrait of himself? It would be nice to have a face to put with this portfolio of atmospheric prints.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.