Scientist of the Day - Johannes Schmidt

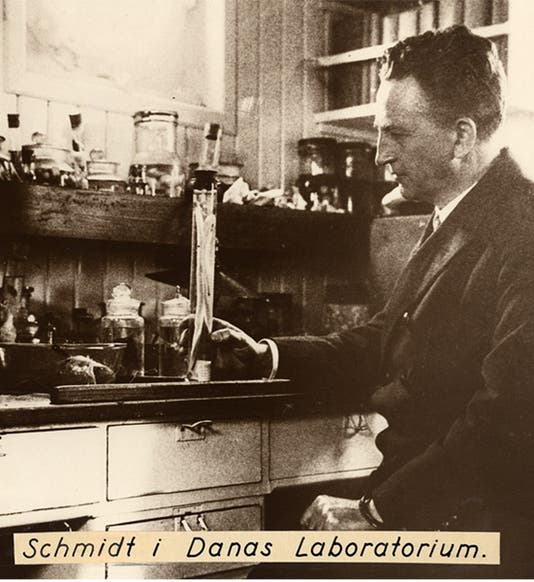

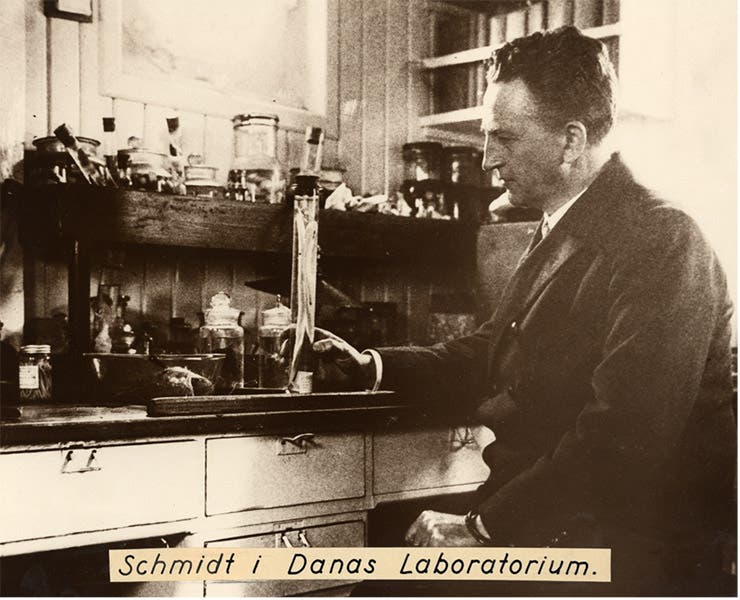

Ernst Johannes Schmidt, a Danish marine biologist, died Feb. 21, 1933, at age 56. Schmidt grew up in Copenhagen and spent quite a bit of his youth in the lab of his uncle, who worked at Carslberg Brewery, which prided itself on supporting pure research. Schmidt studied at the University of Copenhagen and wrote his doctoral dissertation on mangroves, but upon receiving his PhD in 1903, he: a) married the daughter of the director of the Carlsberg Brewery, and: b) switched his interest to marine zoology in general, and to the European eel, in particular, known now to zoologists as Anguilla anguilla, but in Schmidt’s time, called Anguilla vulgaris (second image).

The "eel question" was a burning problem in 1903 – some called it the last great unsolved question in zoology (yes, that was an overstatement, but zoologists said it, nevertheless). The question was actually two-fold: where does the eel come from, and where does it go? Fishermen knew that tiny transparent glass eels showed up in ocean bays and inlets every spring; that they soon metamorphized into yellow-brown eels, which moved up into freshwater habitats all over Europe, and that they stayed there an extraordinarily long time, half-a-century in some cases. The yellow-brown eels had no reproductive organs that anyone could find. Then, in response to stimuli unknown, one day they headed downstream, metamorphosed into silver eels and slowly lost their entire digestive system, developed reproductive organs, readapted to salt water, and when they reached the Atlantic Ocean, they disappeared, presumably headed westward to reproduce with their newly acquired organs of generation. But no one knew where that was.

First paragraph, “Danish researches in the Atlantic and Mediterranean on the life-history of the fresh-water eel (Anguilla vulgaris),” by Johannes Schmidt, Internationale Revue der gesamten Hydrobiologie und Hydrographie, vol. 5, 1912 (Linda Hall Library)

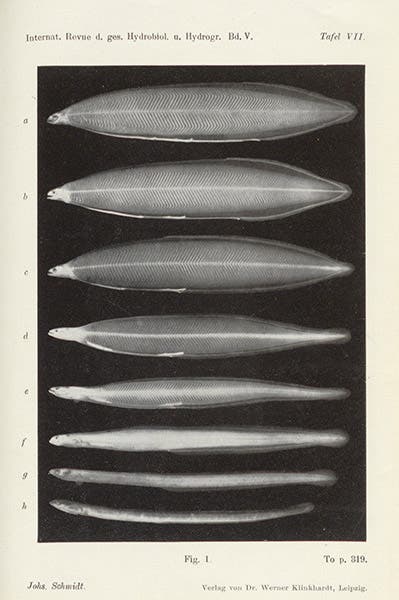

Willow-leaf larvae of the European eel, with two elvers (glass eels) at the bottom, in “Danish researches in the Atlantic and Mediterranean on the life-history of the fresh-water eel (Anguilla vulgaris),” Internationale Revue der gesamten Hydrobiologie und Hydrographie, vol. 5, 1912 (Linda Hall Library)

The only new piece of information discovered in the 2000 years since Aristotle wrote about the eel was the announcement, made in 1896 by two Italian researchers, that a marine species known as Leptocephalus, minute transparent things that resembled tiny willow leaves, were actually eel larvae, which metamorphosized into glass eels when they reached coastal waters. Since willow-leaf larvae were found throughout the Mediterranean Sea, the Italians proposed that the Mediterranean was the long-sought spawning ground of the eel. That is where matters stood when Schmidt, unconvinced by the Italian arguments and evidence, determined to solve the "eel question" in a more definitive manner.

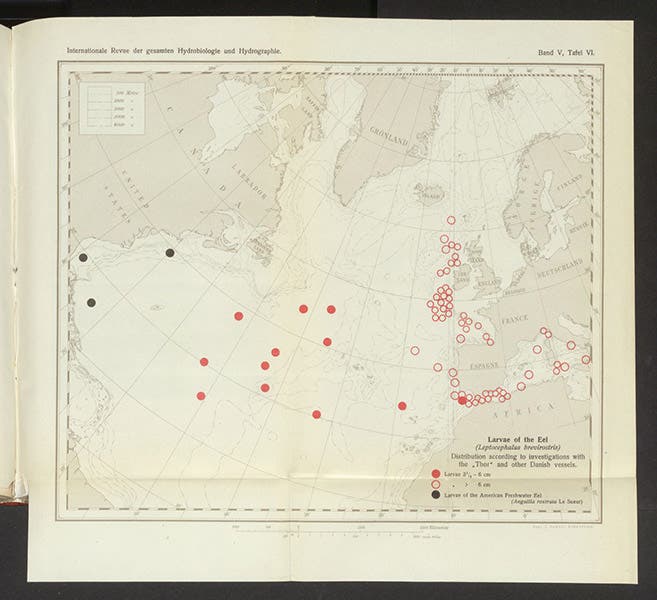

Map showing locations of captured willow-leaf larvae; the open circles indicate larvae larger than 6 cm.; the closed red circles are where larvae smaller than 6 cm. were captured, in “Danish researches in the Atlantic and Mediterranean on the life-history of the fresh-water eel (Anguilla vulgaris),” by Johannes Schmidt, Internationale Revue der gesamten Hydrobiologie und Hydrographie, vol. 5, 1912 (Linda Hall Library)

Schmidt set off on the Thor, a research trawler, sponsored by the Carlsberg Brewery, searching for eels and their larvae. He would spend 20 years in this pursuit. Thor was not a deep-ocean vessel, so his initial forays were along coastlines, trawling for whatever kinds of eels showed up in his nets. He noted that the Mediterranean willow-leafs were large for larvae, sometimes several inches long, leading him to suspect that they came to the Mediterranean from somewhere else. When he found similar-sized willow-leafs in the North Sea, far from the Mediterranean, he felt confident that smaller larvae would be found further west in the Atlantic. And he found them. He enlisted the help of commercial vessels crossing the Atlantic, providing them with nets and instructions, and smaller larvae were found as well as silver eels. He published a preliminary paper in 1912, which included a photograph of the larger willow-leafs and several glass eels for comparison (fourth image). But most importantly, he included a map that showed that the larger eel larvae were found along the European coast and in the Mediterranean but all of the smaller ones, smaller than 6 cm., came from the mid-Atlantic ocean (fifth image).

Paper cover, “The breeding places of the eel,” by Johannes Schmidt, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, ser. B, vol. 211, 1922 (Linda Hall Library)

First paragraph, “The breeding places of the eel,” by Johannes Schmidt, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, ser. B, vol. 211, 1922 (Linda Hall Library)

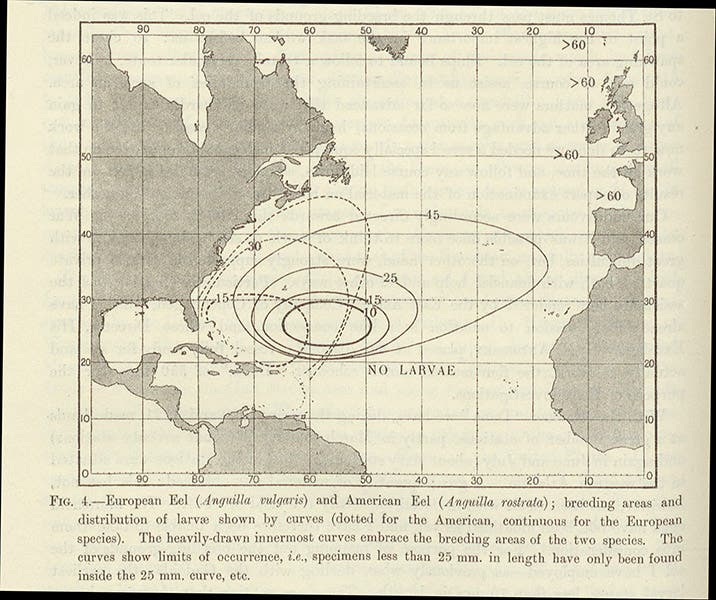

Ultimately, Schmidt secured the use of a larger vessel, the Dana, which he would lead on three Atlantic voyages from 1920 to 1922 (there was a fourth voyage later, in 1928-30). The expeditions were sponsored by the Carlsberg Foundation. From evidence gathered on the Dana (and its successor, Dana II), mostly smaller and smaller larvae, he was able to locate the spawning ground of the European eel in the Sargasso Sea, that sea-within-a-sea that is surrounded by four distinct currents and lies northeast of the West Indies. Schmidt published his definitive paper, “The breeding places of the eel,” in 1922 in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (sixth and seventh images). This included a map of the North Atlantic, with circles defined by diminishing larvae size, surrounding the Sargasso Sea (eighth image).

Map narrowing the breeding location of the European eel to the Sargasso Sea, the circles defined by decreasing larvae size, in “The breeding places of the eel,” by Johannes Schmidt, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, ser. B, vol. 211, 1922 (Linda Hall Library)

That said, Schmidt found no eels or willow-leaf larvae in the Sargasso Sea. Rather, he made a logical conclusion from observations that the silver eels headed in that direction and the willow-leafs came from that direction and got larger as they did so. Not only did Schmidt find no direct evidence that eels spawn in the Sargasso Sea, neither did anyone else, for exactly 100 years after his paper was published, until last fall, when it was announced that 26 female eels had been given satellite tags in the Azores, and five of them showed up in the Sargasso Sea. But still, no one has captured a single eel or larva in the Sargasso Sea, not even a dead one, or the remains of one in the stomach of a predator. Schmidt received the Darwin Medal in 1930 from the Royal Society for solving the eel question. But it sounds as though there are a lot of eel questions still to be answered.

Schmidt eventually published an eleven-part narrative of the four voyages of the Dana, and we have this in our collections too, although it appeared well after the 1922 paper, which is considered authoritative. Schmidt died in 1933, from influenza. If you would like to learn more about the history of our knowledge (or lack thereof) concerning eels, with an excellent chapter on Schmidt, I highly recommend The Book of Eels, by Patrik Svensson, published in English in 2020. It was written and printed before the successful tracking of the five eels into the Sargasso Sea last year.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.