Scientist of the Day - John Auldjo

John Auldjo, a Canadian/British traveler, socialite, and occasional diplomat, was born July 26, 1805, in Montreal. He attended Trinity College, Cambridge and then embarked on his Grand Tour, from which, in a very real sense, he never returned. He climbed Mont Blanc in 1827, wrote and published a book about it, which sold well, and then he moved to Naples, where he would spend a good portion of his remaining years. Having climbed one mountain that was tall and cold, he apparently decided to tackle one that was short and hot, and he didn't have to go far to find such a peak, since Mount Vesuvius lay just across the bay from Naples. In 1831 and 1832, Vesuvius was especially active, and during the later months of 1831 and the winter of 1832, Auldjo visited the summit often, with his sketch pad in hand. He made drawings of new cinder cones and fresh lava flows, and sketched a splendid panorama of the crater at the summit of Vesuvius

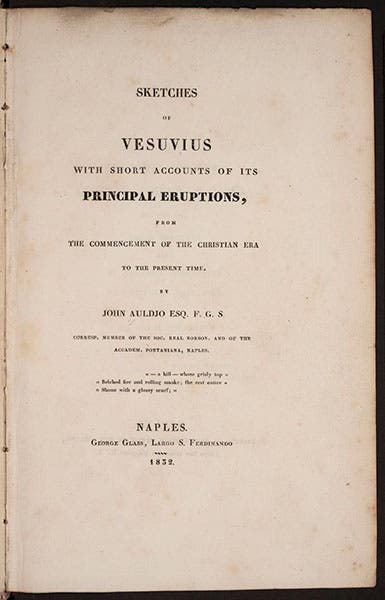

In 1832, he published a book, Sketches of Vesuvius, with a rather unexciting narrative of the principal eruptions of Vesuvius throughout history, accompanied by a very exciting series of hand-colored lithographs made from his sketches. There are 17 of them in the slim 96-page octavo volume, and together they comprise the most delightful series of volcanic scenes you could ever hope to find. We have this book in our collections, and it is one of my very favorites.

So why have I not written about Auldjo and Vesuvius before? Well, I have – I did a post on Auldjo four years ago, on this day. But due to the limitations of our format, I could only include five plates from the book, and two of these showed the same plate – the wonderful panorama in its entirety, plus a closeup of Auldjo himself, leaning on a boulder. That post may be viewed here, and you might want to look at it before going any further

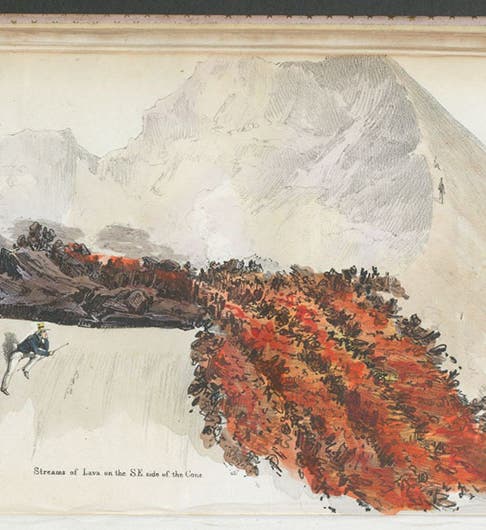

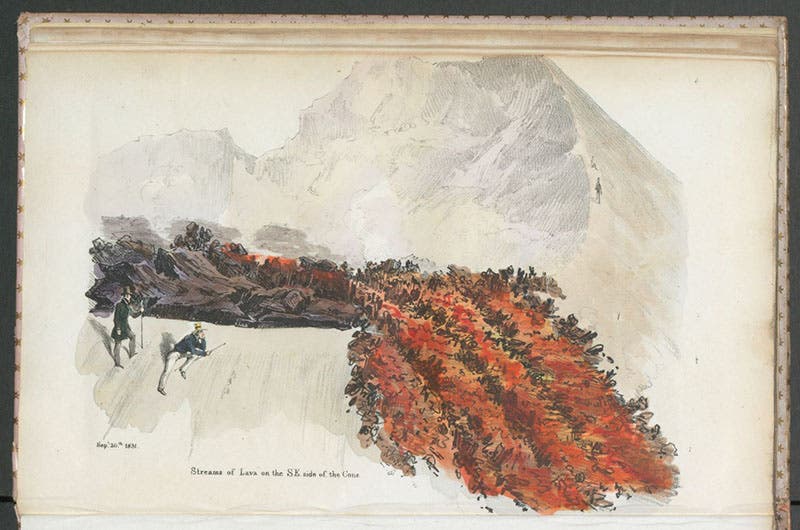

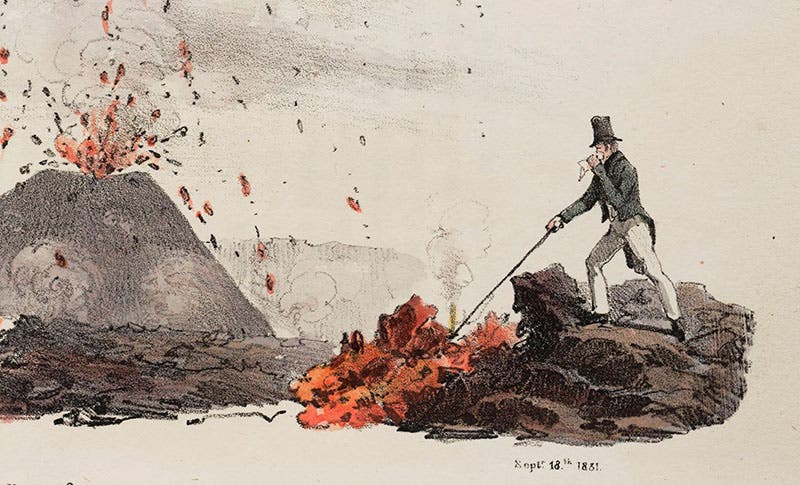

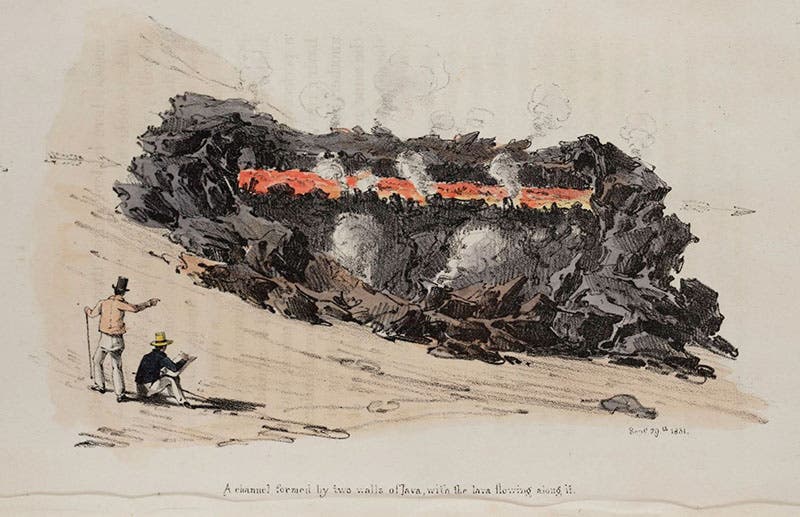

There are two features that make these lithographs so appealing – well, three, if we include the fact that Auldjo drew them all. First, nearly all of them are dated, so that our first image, showing a stream of lava breaking out of the crater, carries the date: Sep. 20, 1831. This ties the images to the text in a very precise way. Second, Auldjo has placed himself in nearly every illustration – he is readily identifiable with his tall white hat with the dark band and his improbably white trousers. The one exception is our fourth image, where he depicts another member of his party poking at a pool of lava and filtering out some of the sulfurous smell with a handkerchief, as if Auldjo were saying, well, I am daring, but I am not crazy. This, incidentally, is a detail of a larger plate, which we showed in full in our first post on Auldjo. In one of the scenes here (sixth image), Auldjo sketches himself sketching, just to remind the viewer where these images came from.

A great deal of the appeal of these lithographs comes from the bright orange lava. If nothing were erupting, we would have a series of gray and black landscapes (and people in white pants) with much less eye appeal. The lava really makes things pop, as they say.

Also interesting to me is the fact that Auldjo sent the book to the printers early in 1832, after which there was another small eruption, which he observed firsthand and recorded on his sketchpad. Since the type for the book was already being set at the time, he wrote an appendix, had his new sketches converted to lithographs, and just tacked them on at the end. His sketch of "A grotto in the lava" is one of those late additions (seventh image).

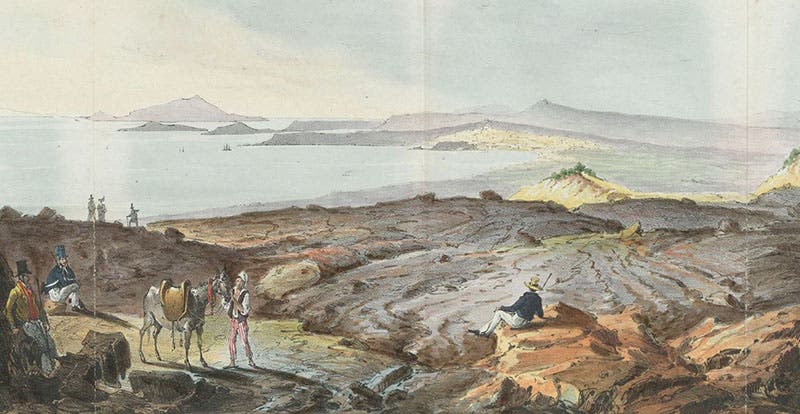

Two plates have a different tone from the lava scenes. Near the beginning of the Sketches, there is a folding plate that shows "The Hermitage," which was apparently the staging spot for tourists off to climb the volcano (fourth image). Auldjo says he drew this with some kind of a camera obscura or camera lucida. Another plate takes a look back at Naples from the flanks of Mount Vesuvius (eighth image). You can hardly make out any details of the city, but it is there, across the bay. However, you can certainly make out Auldjo, sitting on a rock at image center.

We bought our copy of Auldjo’s Sketches on the very first day of the auction of the Honeyman Collection, on Oct. 30, 1978. Bruce Bradley and I had been on the job for only a few months and were inexperienced at pricing rare books and bidding at auction. Fortunately, we had the eminent rare book dealer Jake Zeitlin bidding for us in London, and when he called after our bids on the first hundred lots had come up empty and said we should double all our bids, we did just that, and lo and behold, we got the Auldjo. The price, which seemed high at the time, was, in hindsight, a great bargain. It is such a beautiful book that we have displayed it twice in exhibitions: in Vulcan’s Forge and Fingal’s Cave in 2004, and in Crayon and Stone (an exhibit on 19th-century lithography) in 2013. Given the chance, we will display it again, even if we will almost certainly open the book to the same multi-fold panorama. It is such a magnificent plate!

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![A grotto in the lava,” [Feb., 1932], hand-colored lithograph from a drawing by John Auldjo, in his Sketches of Vesuvius, 1832 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/e1e421e1-cc81-4f48-b0ab-6937285d299f/auldjo7.jpg?w=800&h=535&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)