Scientist of the Day - John Barrow

John Barrow, English civil servant, died Nov. 23, 1848, at age 84. Barrow was Second (Permanent) Secretary of the Admiralty of the British Royal Navy for over forty years, and it was his idea in 1818 to send out some ships to search for a Northwest Passage. The first ships did not find the passage, but they found enough surprises to warrant further expeditions. Barrow sent ships up Baffin Bay, more ships around Alaska, and expeditions overland through Hudson’s Bay Company territory. The results of each of these voyages or expeditions were printed up in sumptuous volumes with tantalizing images of the world of the North. We have written about many of the Arctic explorers that Barrow sent out, including Edward Parry, James Clark Ross, George Back, and John Franklin, and we displayed many of those works in our 2008 exhibition, Ice: A Victorian Romance. Barrow lived long enough to propose in 1845 what turned out to be the famous Franklin expedition, yet another quest for a Northwest Passage, but not long enough to learn that all hands perished along with the ships. Barrow gave his name to Point Barrow, Alaska; Cape Barrow, Nunavut; and Barrow Strait, in the Arctic archipelago.

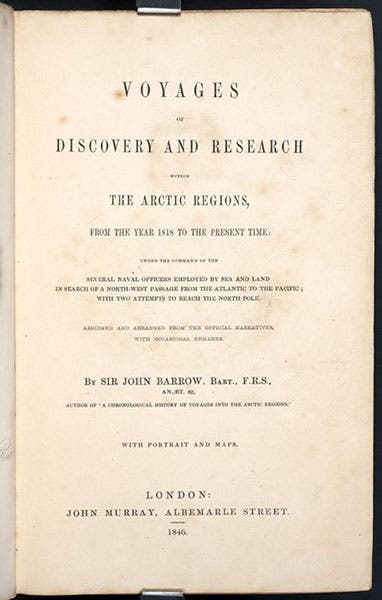

Barrow was proud of all the expeditions he sent out except the very first, which was led by John Ross in HMS Isabella, seconded by Edward Parry in HMS Alexander. Their mission was to sail up Baffin Bay between Greenland and North America to look for an outlet to the west. Lancaster Sound near the top of Baffin Bay, seemed promising to Parry and to officers on board Ross’s ship, but Ross claimed that he saw a chain of mountains walling off the west end of the sound – mountains no one else observed – and he turned around and headed home, without even staying the winter. Barrow was livid about this defection from orders, and when, the next year, Parry sailed right through the imagined mountains and made it halfway across the Arctic archipelago, Ross cut Admiralty ties with Ross and ensured he would never get another command. Twenty-eight years later, Barrow was still upset, and when he published his history of attempts to find a northwest passage in 1846, he spent the entire second chapter ragging on Ross as a disgrace to the Navy, and his account of Ross’s second attempt in the 1830s to penetrate the Arctic (privately financed, since the Royal Navy would have nothing to do with him) was just as disparaging. Barrow could certainly hold a grudge. His book was called: Voyages of Discovery and Research within the Arctic Regions, from the year 1818 to the Present Time (1846). Most of our images today are from this book.

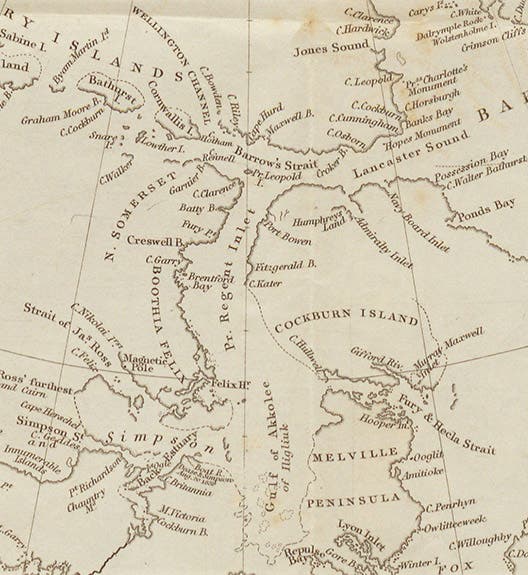

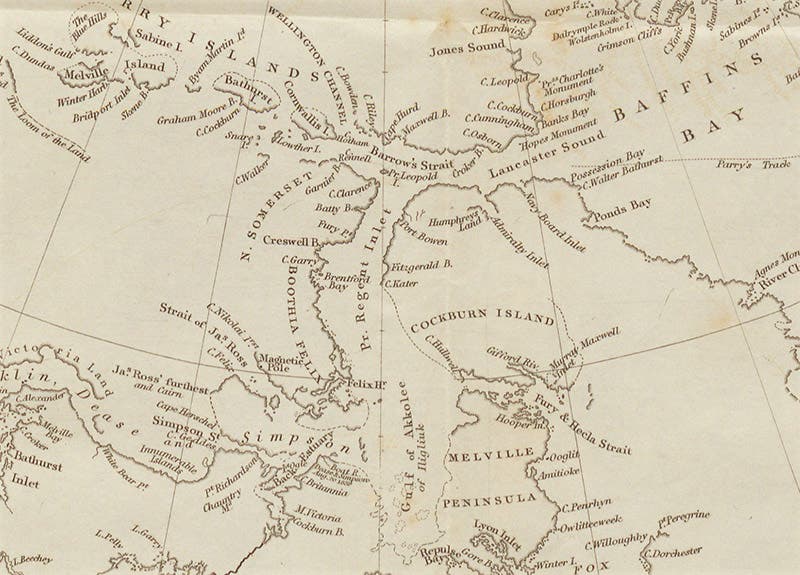

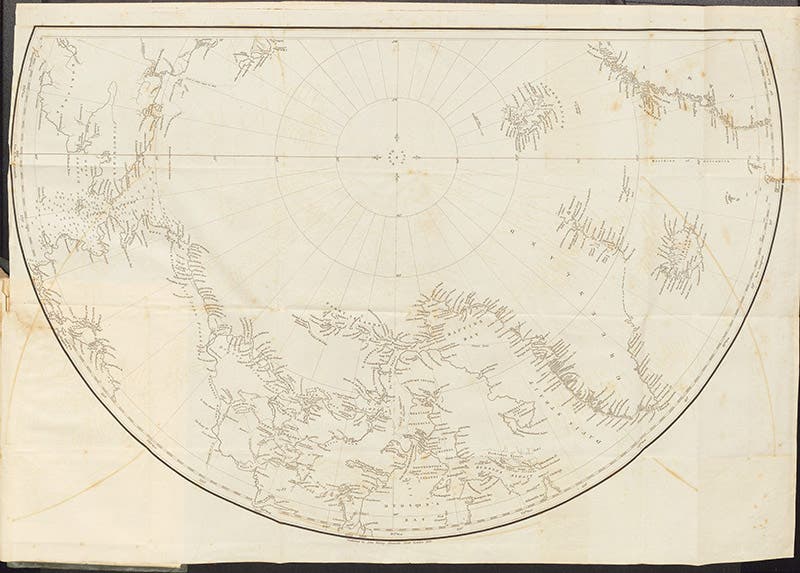

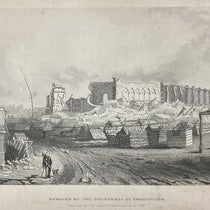

In spite of the attention given to Ross, Barrow’s purpose in writing the book was to provide a low-priced account of Arctic adventuring that readers could afford, unlike the high-priced official narratives with their hand-colored lithographs, such as the volumes we displayed in our exhibition. The only substantial illustration in Barrow’s book, other than the portrait frontispiece, is a fold-out map at the end. It shows quite a few named islands and straits, none of which were known to exist when Barrow sent out his first ships in 1818. However, there are vast blank areas on the left side of the map, indicating regions yet unexplored, which was why Barrow was so anxious to send out another expedition – the Franklin expedition – to complete what he and the Navy had started. We displayed this map in Ice: A Victorian Romance, and showed a detail in our exhibition catalog. We show the complete map and a different detail here (first and fourth images).

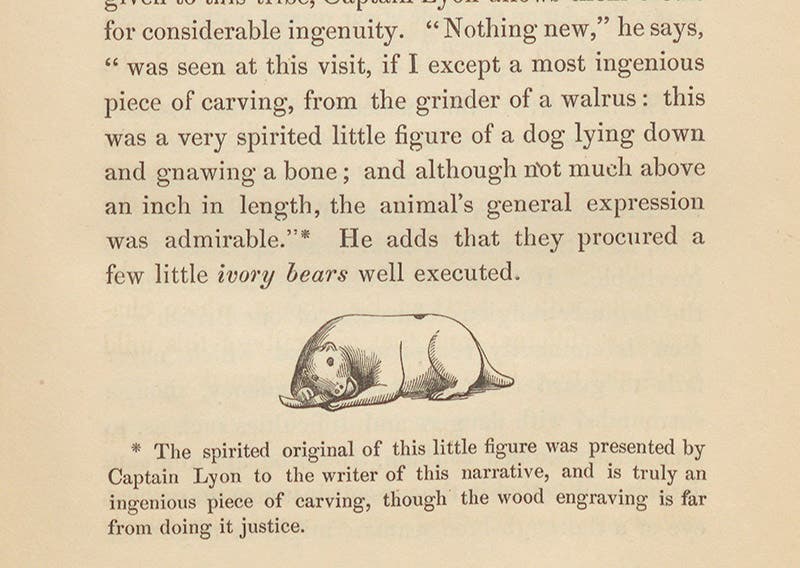

In my description of the book for the catalog, I stated that the book had no illustrations except for the frontispiece portrait and the map. I was wrong – there is one small woodcut, and I atone for my mistake by displaying it here (fifth image). It shows a tiny bit of scrimshaw, carved from a walrus tooth, in the form of a dog gnawing on a bone. It was obtained by George Lyon, one of Barrow’s Arctic officers, from an Inuit artist living along Hudson Bay, and given to Barrow, who treasured it enough to include it in his memoirs.

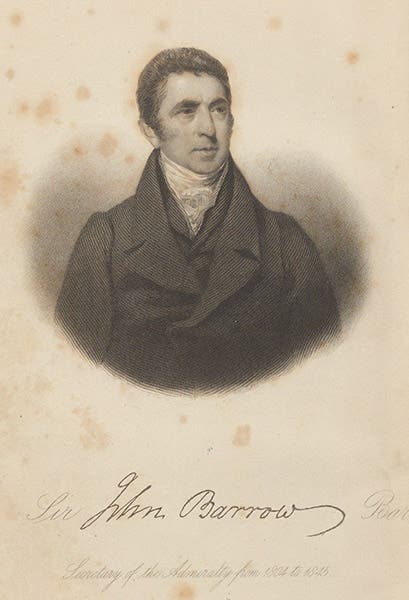

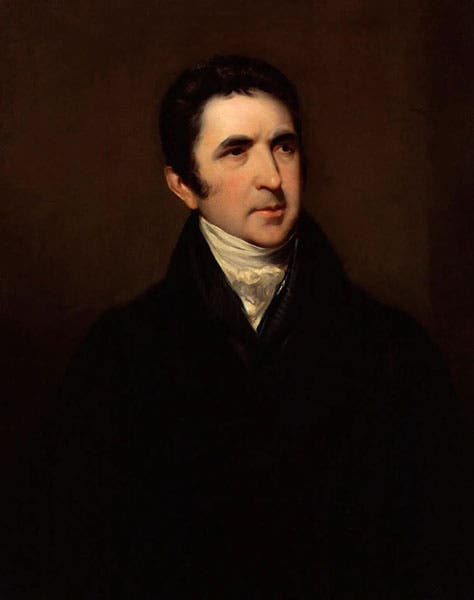

The portrait of Barrow in our copy of his book (second image) was engraved from an oil portrait made in 1810, attributed to John Jackson. That painting is in the National Portrait Gallery, and we include it here (sixth image), so you can compare it to the engraving. It is interesting that Barrow, for his frontispiece, used a portrait of himself made 35 years earlier, before he had even sent out his first ship. Perhaps there were no other portraits available – the only other one in the National Portrait Gallery is a mezzotint dated 1847.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.