Scientist of the Day - John Canton

John Canton, a British mathematician and schoolmaster, was born July 31, 1718, in Stroud, Gloucestershire. He built a sundial of his own design while still a student in Stroud, which came to the attention of a resident of Stroud who had moved to London and was a Fellow of the Royal Society there. He invited his young fellow Stroudian to come to London and join the faculty of a nonconformist school. Canton did just that.

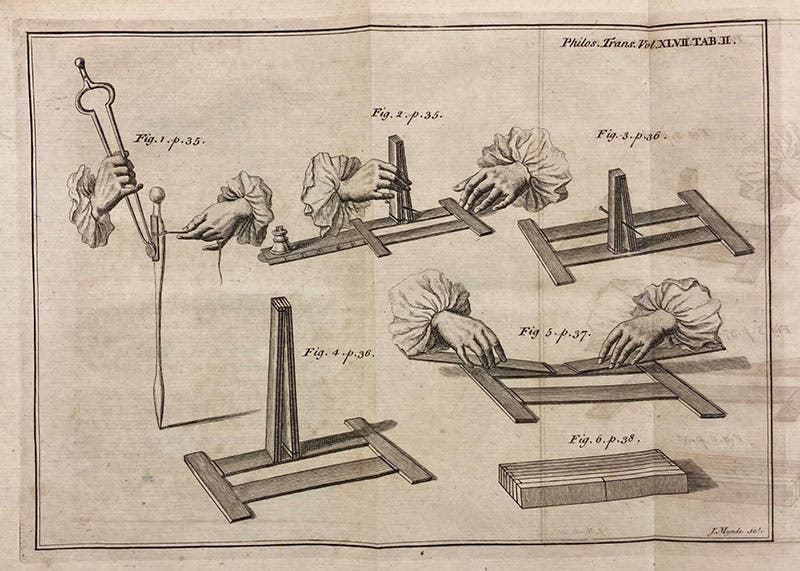

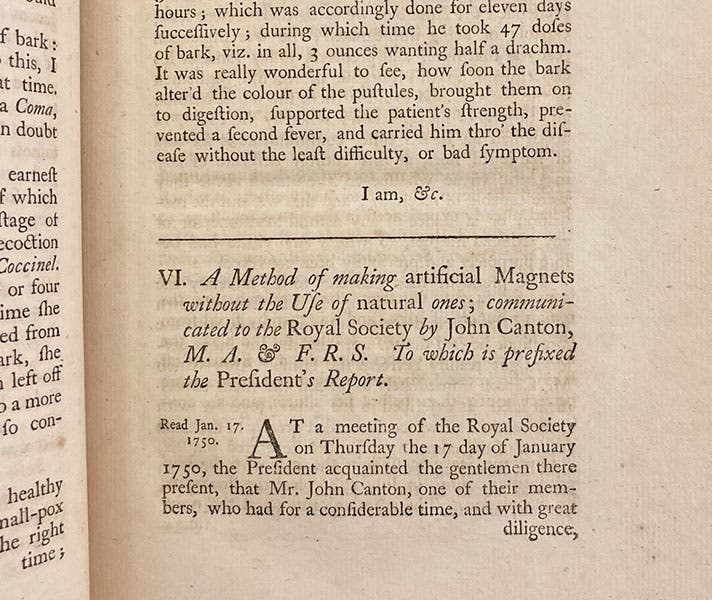

I cannot determine what Canton did for the next ten years, except presumably teach school, but in 1750, there he was, reading a paper before the Royal Society revealing that he had discovered a method of magnetizing iron that did not involve the use of another magnet. He called these “artificial” magnets (since no real magnet was involved), and these magnets were more powerful than those made the old way by stroking iron bars with magnets. I read his paper twice and still cannot understand the process, except it involves stroking an iron bar on a poker and then placing iron and steel bars in various arrangements where they touch briefly (first image). The Royal Society was apparently more impressed than I am, for they not only elected Canton to membership, but the next year they awarded him the Copley Medal, which was their highest annual honor. The Copley Medal had been first awarded in 1731 (to electrician Stephen Gray), and in the following years had been given to the likes of John Theophilus Desaguliers (three times), Stephen Hales, Abraham Trembley, and Henry Baker. Canton doesn't seem to belong in that company, in our eyes, especially after Benjamin Franklin won the medal two years after Canton.

Canton continued to do original work – he invented the pith-ball electrometer in 1754, which consists of two small and very light paste balls suspended by silk threads from a common point. If you bring an electric charge anywhere near them, the balls fly apart, indicating the presence of an electrically charged object. In 1762, Canton published another paper in which he showed that water is not incompressible. contrary to the common belief of just about everyone.

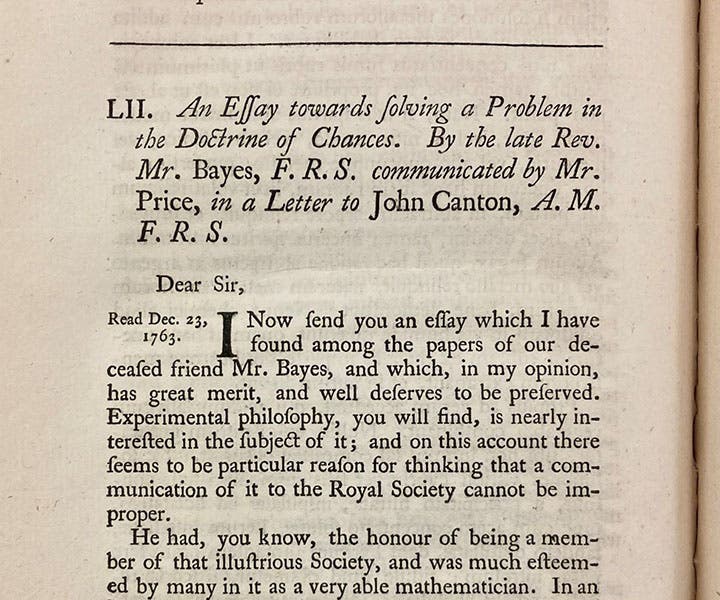

But to me, the most remarkable feature of Canton's career is that he was responsible for publishing Bayes’ Theorem in 1763. Thomas Bayes was an obscure English mathematician who discovered inverse or conditional probability in the 1740s and wrote up a paper on the subject. Inverse probability, as the name suggests, turns questions about probability around. Whereas the ordinary rules of probability address such problems as "what is the probability of drawing a yellow marble, if you draw three marbles from a sack containing 10 yellow marbles and 90 white marbles.” Bayes asked instead (and this is a modern example, not his): "If I draw five marbles from a sack, and one is yellow and four are white, what is the probable distribution of the marbles in the sack?" The advantage of inverse probability is that predictions can be continually refined as experience accumulates, so that if you draw five more marbles, and they are all white, that will change the probability prediction (and drawing a blue marble would change it even more), but Bayes’ theorem can easily accommodate any and all new information. "Bayesian methods” and “Bayes’ Theorem” have been used in recent decades to locate lost airplanes, and the terms have occasionally been in the news, in case any of this sounds familiar to you.

Bayes' paper was called "An Essay towards solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances," but he never published it. When he died, which we think was about 1761, his executor, Richard Price, found it among Bayes' effects, and after making some changes, he sent it, remarkably, to John Canton. I do not know what the connection was between the two. But Canton was impressed, and he read it before a gathering of Fellows on Dec. 23, 1763, and the paper was then published it in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society for 1763. The paper was generally ignored at the time, and when, ten years later, Pierre-Simon Laplace independently discovered the rules of inverse probability, he was given the credit (although Laplace himself later learned about Bayes’ priority and gave Bayes the credit). For the next century and a half, most statisticians did not consider Bayesian methods to be reputable, since they often involved making hunches and using gut feelings. It was not until 1950 that the famous geneticist and mathematician R.A. Fisher first applied Bayes’ name to the methods of conditional probability, and since then, Bayes’ reputation has been gradually restored. And we have John Canton to thank for making Bayesian methods known to the world.

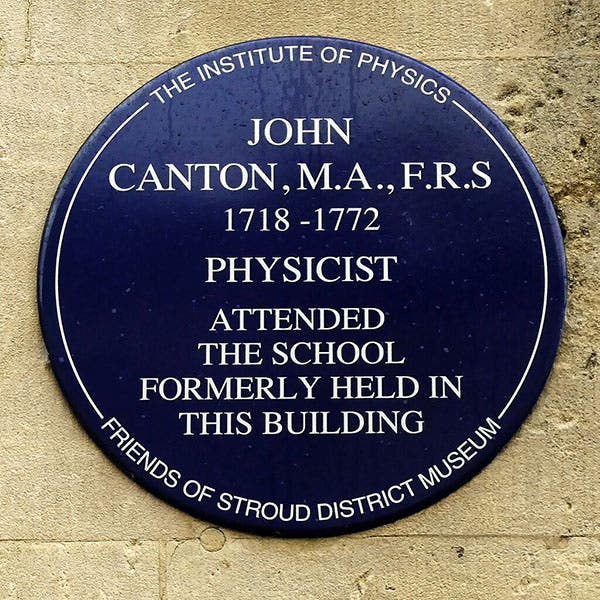

Canton died in 1772 in Spitalfields and was buried in a cemetery in Islington in Greater London. There is no grave marker. There is a plaque honoring Canton on a wall in The Shambles (the old meat market) in Stroud, his birthplace, indicating that Canton attended school there. It is just about the only public monument you will find for the mysterious Mr. Canton. I wonder what the probability is that he will one day appear on a British postage stamp?

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.