Scientist of the Day - John Franklin Enders

John Franklin Enders, an American medical scientist, died Sep. 8, 1985, at age 88. Enders was raised in West Hartford, Connecticut (where I myself went through middle and high school). His family was wealthy, and John piddled around for some years, went to Yale, served in the Navy air corps during WWI, and then decided to pursue a PhD in philology at Harvard. He was clearly in the wrong business, as his choices for his doctoral thesis indicate: "Alchemy and its influence on English literature,” and “The Doctor and other medical characters in the Drama until 1800." Finally, he discovered Hans Zinsser, head of the bacteriology department at Harvard, who was soon to be the author of a medical classic, Rats, Lice, and History (1935). Finally acknowledging his attraction to medical science, Enders gave up philology for bacteriology, and eventually he was lured to viruses, setting up a research laboratory for infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital in Boston. After working on mumps and chicken pox, he developed techniques for growing viruses in live tissue culture, essential for the development of vaccines. In 1949, he and two younger colleagues succeeded in growing the polio virus in tissue cultures. It was this that enabled Jonas Salk to develop a vaccine against polio, that dreaded scourge of the early fifties, and it was for this achievement that Enders and his two colleagues received the Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine in 1954.

Enders next tackled the virus that causes measles, that other great childhood affliction. By 1954, Enders had succeeded in growing the measles virus in tissue culture, and by 1955, he had written a paper describing the path to the development of a live attenuated measles vaccine, which led in turn to the successful production of such a vaccine. In 1981, when he was 84 years old, Enders received the Galen Medal from the Society of Apothecaries in London – the first time the award had ever been given for preventive medicine – and the presenter said something I would like to quote: "Measles is a disease of the human race. There is no animal reservoir, there is no insect vector, and there is only one antigenic strain of virus. Measles is therefore not only a preventable disease, but one that can be eliminated, given the necessary resources and drive. It must be a source of great gratification to you, Dr. Enders, to see what great strides have been made in the United States to control measles by immunization." One can't help but wonder what Enders would think if he were plucked from his grave and plunked down in the middle of a modern talk show, to learn that the successful eradication of measles is being threatened by anti-vaccinationists who claim, on the basis of no legitimate evidence whatsoever, that measles vaccination causes autism and is more hazardous to children than the disease itself. He might well wonder what has happened to the American public, that it now takes advice on medical matters from ex-playmates and home-schooling gurus, and he would no doubt express a fond hope that he might be quickly returned to his final resting spot.

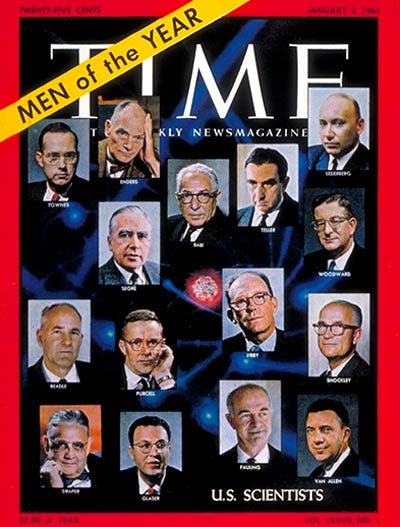

We have several times mentioned the cover of Time Magazine for Jan. 2, 1961, when Time selected 15 scientists for its “Men of the Year” issue, thereby redeeming itself from decades of general neglect of scientists as suitable cover material for its magazine (second image). Enders was one of those 15, and you can see him at the top, second from left, looking somewhat perplexed, as if he had just run across the word “antivaxxer” in the New York Times crossword puzzle.

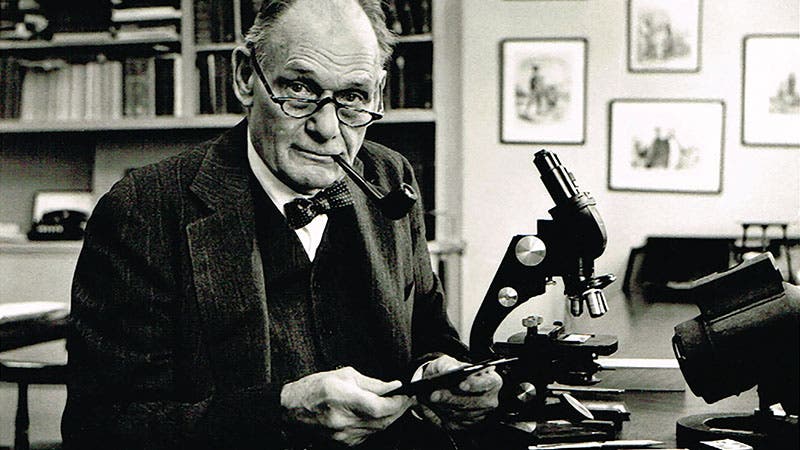

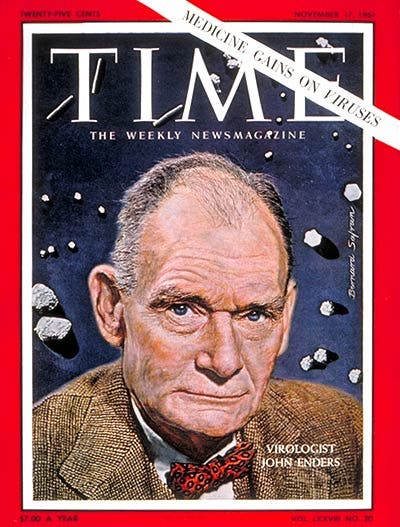

Just ten months later, Enders got his own Time cover, made from a portrait painting by Bernard Safran. The cover story was about recent medical victories over viruses and was called: “Medicine: The ultimate parasite.” It mostly focused on the work of Enders. You can read it here.

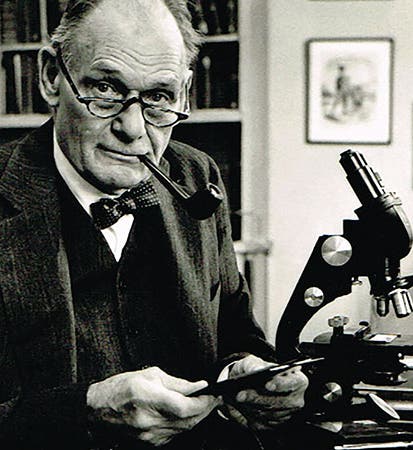

In 1978, Time gave its large collection of portraits painted for Time covers to the National Portrait Gallery in Washington. Safran's portrait of Enders was included, so you may find it there, although I doubt that it is hanging on any of the walls. Here is the original painting without the Time logo.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.