Scientist of the Day - John Navarre Macomb

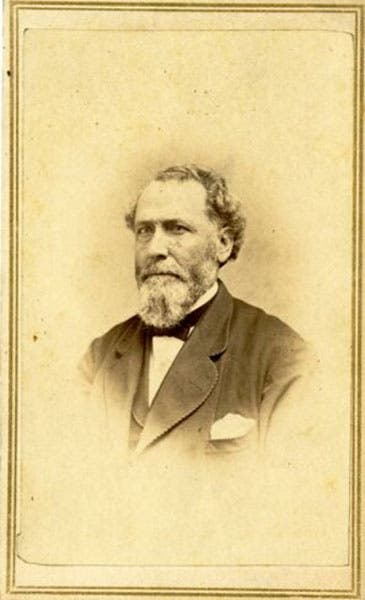

John Navarre Macomb, Jr., an officer in the Corps of Topographical Engineers, died Mar. 16, 1889, at the age of 77. In the late 1850s, Macomb was given the responsibility for building three roads in New Mexico, leading to Santa Fe, and he did such a good job, under budget, that he was offered the chance to take a small group of men north on one of his roads into Colorado, hoping to discover a route for a wagon road to Utah and the San Juan River. The working party numbered only six; there was also a contingent of soldiers for protection from hostile natives (and Mormons). Macomb was fortunate to have in his party John Strong Newberry, a geologist who had just returned from serving with the Joseph Ives expedition, which came up the Colorado River from its mouth by paddle-wheel steamboat in 1857-58. Newberry was not only a highly competent geologist, but a skilled artist as well.

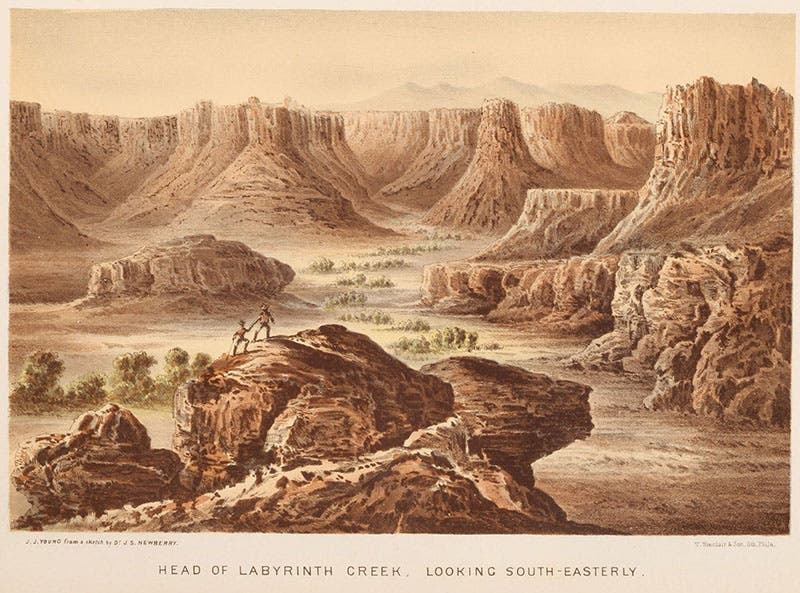

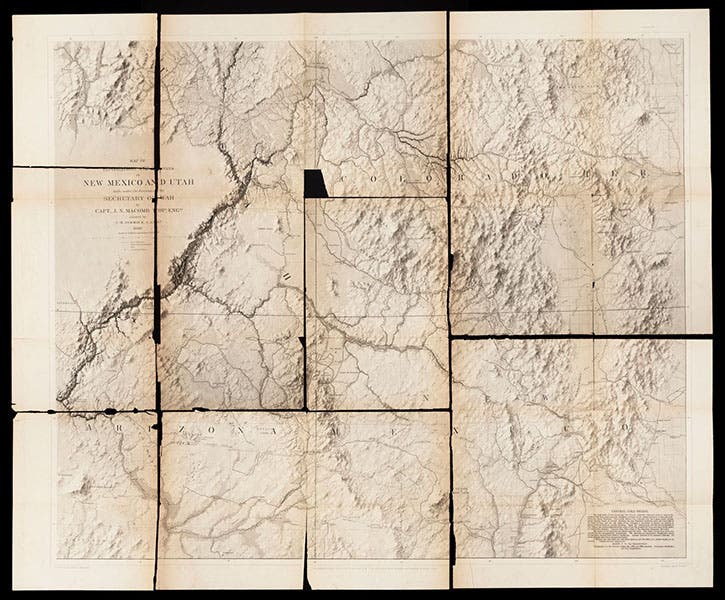

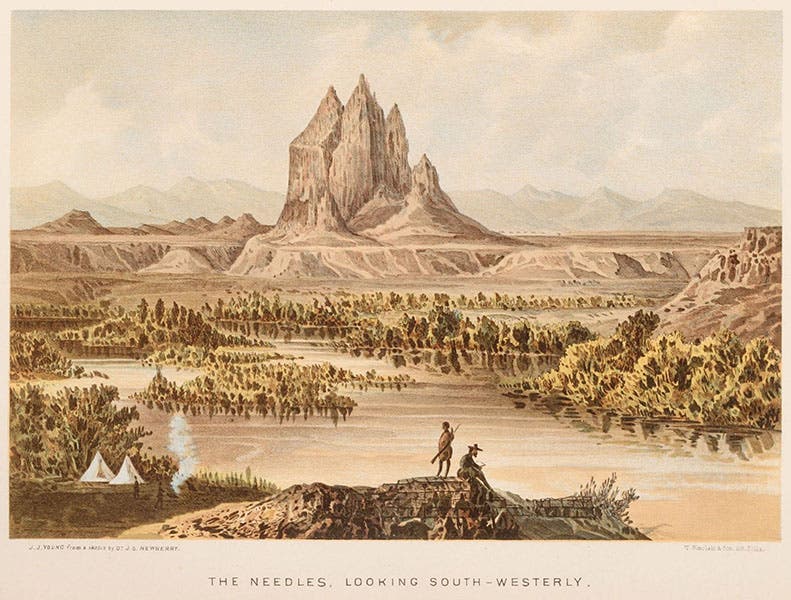

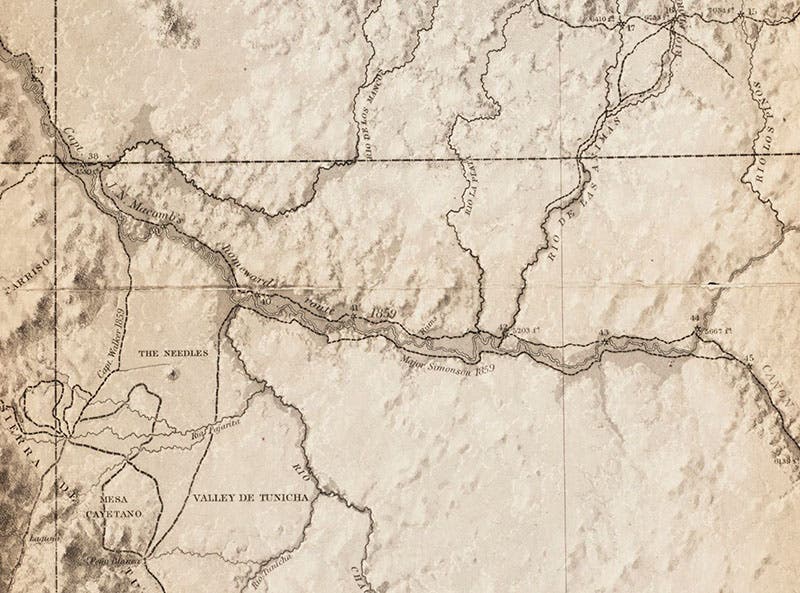

The Macomb expedition went north by horseback into Colorado, beginning in the summer of 1859, crossed the Colorado plateau (which they named the Sage Plateau), and made it all the way to Labyrinth Canyon (first image), near where the Green River merges with the Grand River to become the Colorado River; fourth image), which was a new discovery. They were unable to go any further, because of the depth of the canyons, and thus were unsuccessful in finding a route into Utah from the south. But Newberry made continuous geological observations, comparing the strata in Colorado to those he had recorded in Arizona and New Mexico, and he even found a partial dinosaur skeleton that they sent back to Joseph Leidy in Philadelphia. On the return trip, Macomb took a more southerly route, passing near the future Four Corners area and withing sight of a massive volcanic plug jutting hundreds of feet out of the desert. Macomb called it "The Needles'; it is now known as Shiprock and is a popular tourist destination in northwestern New Mexico. Newbery did a drawing (fifth image), and Macomb also recorded it on his map (sixth image).

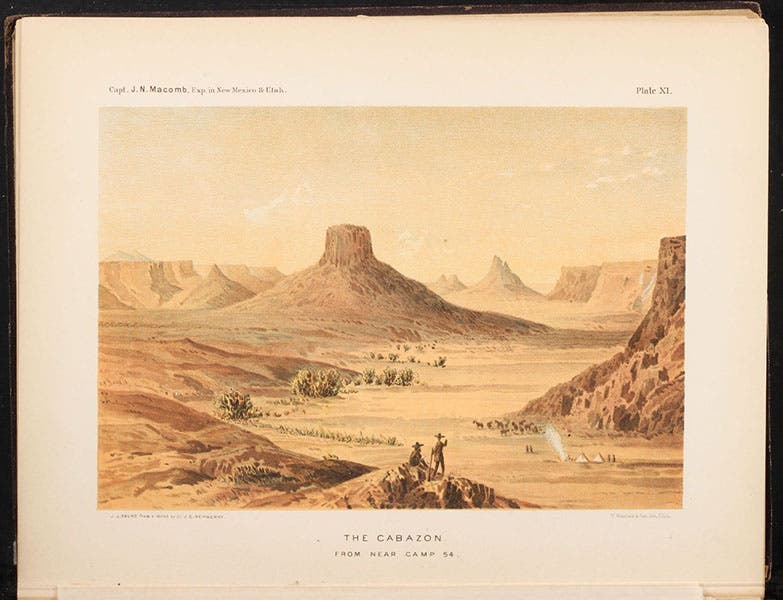

After their return, Macomb wrote up his narrative, and Newberry began to prepare his geological report, but before he could finish, the country began to fall apart with the events leading up to the Civil War. So the narrative of the Macomb expedition of 1859 was shelved, and it did not make it into print until 1876, meaning it was not available to any of the Great post-War Surveys of the West. Why it was printed at all, I do not know, but I am glad it was, for it contains 11 chromolithographs by John J. Young based on drawings by Newberry (first, fifth, and seventh images).

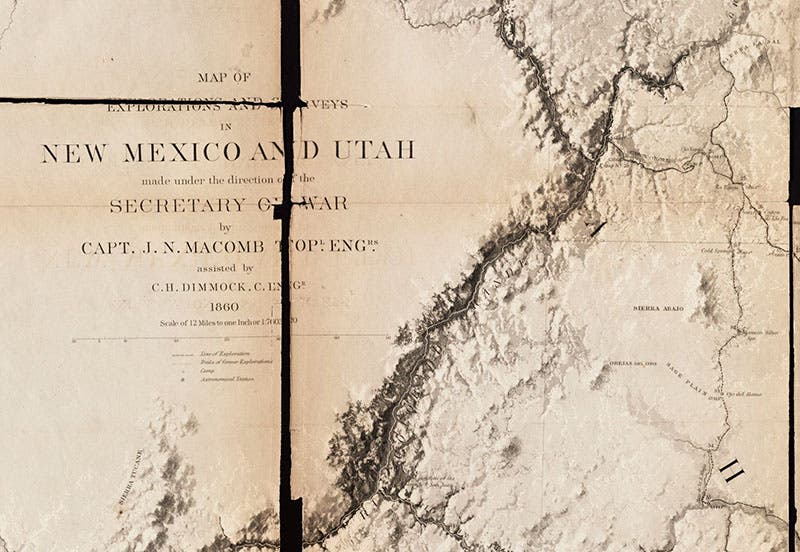

The Report also contains a map by Macomb that he compiled and had engraved in 1860. I do not know if it was published as a broadside map in 1860, but it was definitely included in the 1876 report. As you can see, the map in our copy has come apart at the folds, like many printed paper items from the 1870s, but the technicians in our Digital Initiatives unit did a fine job of piecing it together for a photograph (third image; details in fourth and sixth images). The condition notwithstanding, it is a wonderful map, and it shows each of the 57 campsites of the party, each one numbered, which is fortunate, because the narrative hardly mentions any dates, but regularly specifies the nearest campsite by number when an observation is recorded. Thus the last plate in the book (seventh image) shows a formation called “The Cabazon,” which is not otherwise mentioned in the text, but the caption says it was observed near campsite 54, which puts it within sight of Jemez, New Mexico, just west of Santa Fe.

The narrative of the Macomb expedition is titled: Report of the Exploring Expedition from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to the Junction of the Grand and Green Rivers of the great Colorado of the West, in 1859, under the command of Capt. J.N. Macomb, Corps of Topographical Engineers (eighth image). Most of the Report consists of Newberry’s geological observations (augmented by his 11 landscapes, rendered into lithographs). But Macomb deserves a great deal of credit for getting his men to the Colorado River, and back, without incident, through a countryside that was, geologically and ethnically, extremely unfriendly.

Macomb survived the Civil War, unlike many of his brethren in the Corps, and retired in Washington, D.C., where he died in 1889. He is buried with his family in Arlington National Cemetery, under a modest but attractive tombstone.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.