Scientist of the Day - Joseph Black

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

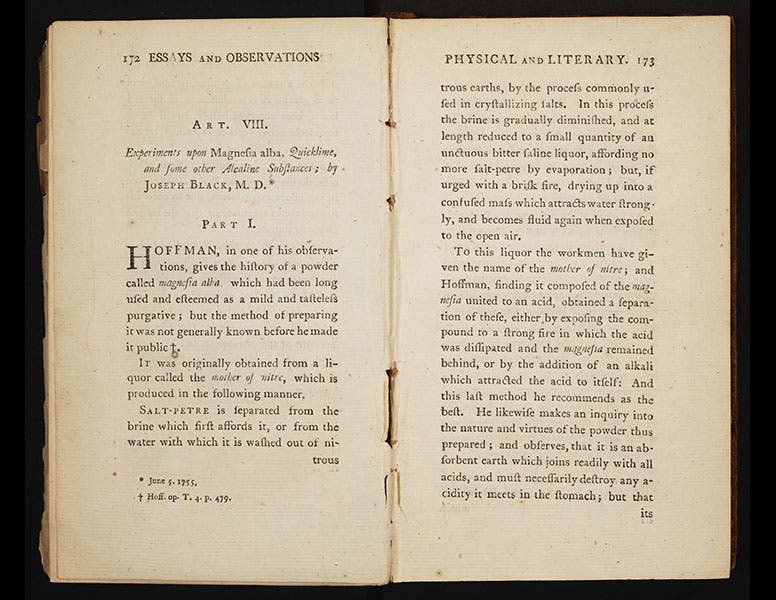

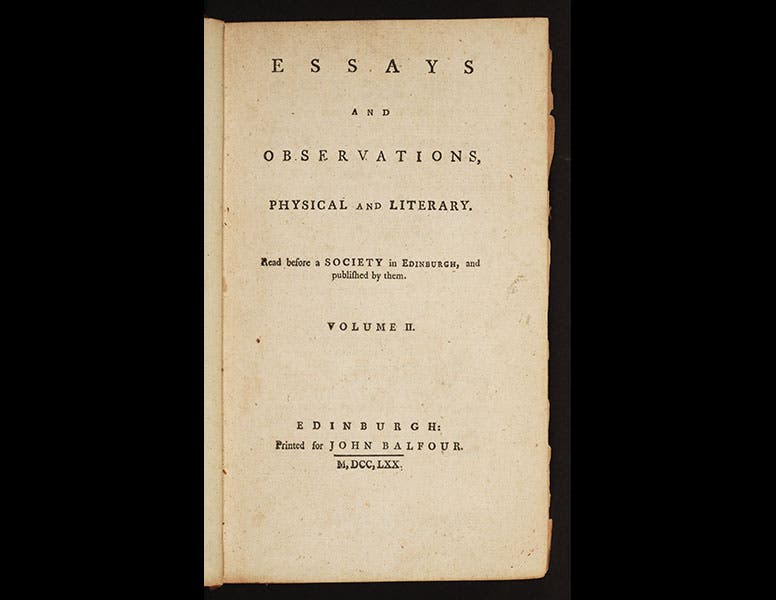

Joseph Black, a Scottish chemist, was born Apr. 16, 1728. In 1754, Black discovered that when you heat magnesia alba (magnesium carbonate), it loses weight, and he found that the weight loss was due to an "air" that is given off during heating. This “air” differs from ordinary air in that it will not support combustion and is soluble in water. The same air could be extracted from other minerals, such as limestone. In 1756, Black presented a paper to the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh in which he described his new gas, which he called "fixed air", because it could be fixed into a solid substance. We now call it carbon dioxide. This was the first of the many gases that would be identified during the chemical revolution of the next twenty-five years. The papers presented to the Philosophical Society over the course of 16 years were published in 3 volumes, which we have in our History of Science Collection; Black's "Experiments upon magnesia alba” is in volume 2 (second and third images).

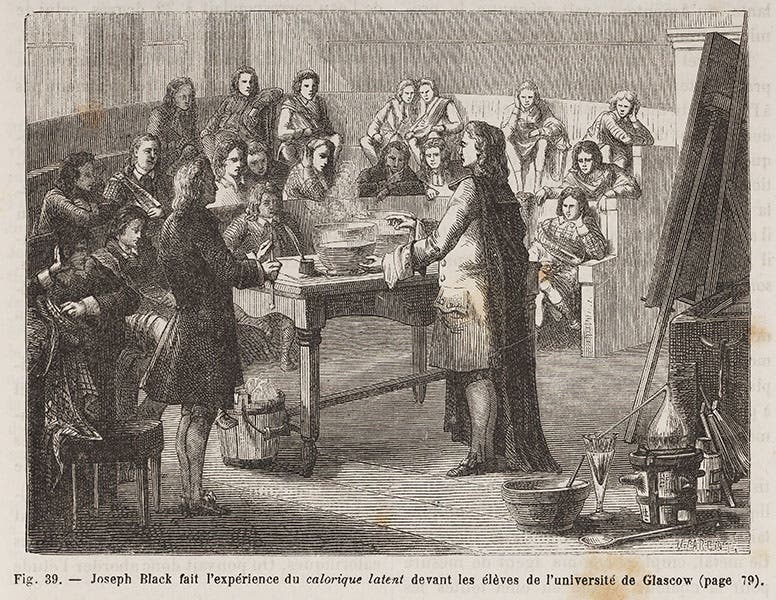

Black also discovered what he called "latent heat," a consequence of his discovery that when you add heat to a body, it does not always raise the temperature--sometimes it changes the state. Thus you can add a considerable amount of heat to ice at 32° F, and the temperature does not rise; instead, the ice slowly melts. There is no contemporary image of Black discovering latent heat, so instead we turn to that often reliable 19th-century source, Louis Figuier's Les merveilles de la science (1867-91), where we find a wood engraving of Black explaining latent heat to a scientific gathering, or so we are told by the caption (fourth image).

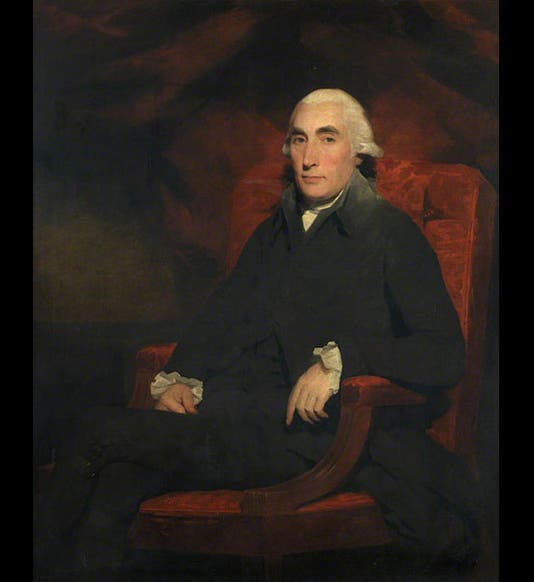

Black taught first at Glasgow, then at Edinburgh, and he spent his later years as a member of an Edinburgh social gathering known as the Oyster Club. Other members included the economist Adam Smith, the geologists James Hutton and John Playfair, and the philosopher David Hume, quite the cream of the Scottish Enlightenment. There are two oil portraits of Black painted by two very fine portrait artists, David Martin (who also painted Benjamin Franklin) and Henry Raeburn (who painted everyone else). We show above the Raeburn portrait, which is in the Hunterian Art Gallery at the University of Glasgow (first image).

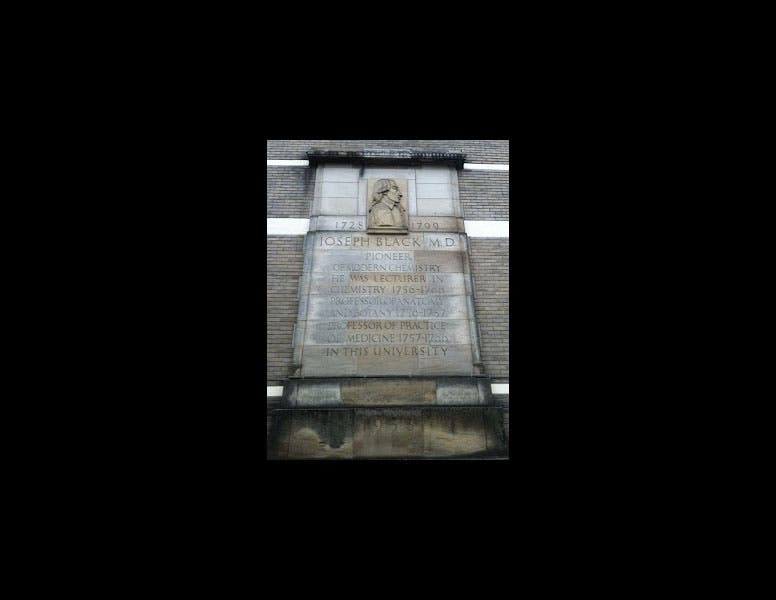

The chemistry building at the University of Glasgow has been named after Black, and there is an impressive stone plaque on the side of the building that commemorates him (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.