Scientist of the Day - Joseph Dixon

Joseph Dixon, an American inventor and manufacturer, was born on Jan. 18, 1799. He grew up in Salem, Massachusetts, not too far from a historic graphite mine called Tantiusques, in Sturbridge. Dixon and his father worked at the mine for a while, and Dixon decided to establish a company to make graphite-lined crucibles to use for melting metals; the company now dates its founding to 1827. By the 1840s, the plant had moved to Jersey City, New Jersey, where it would grow over the course of the next century into an enormous factory. While the principal products were crucibles, and the company was called the Joseph Dixon Crucible Company, Joseph experimented for decades, trying to find a way to manufacture graphite pencils economically. The graphite pencil had been around for quite a while, and Anton and Johann Faber of Germany had long been selling commercial pencils, but Dixon was set on making a good and affordable American pencil, competing, interestingly, with the John Thoreau Company of Concord, Mass., founded by Henry David Thoreau’s father. Dixon pencils were indeed as good as anything the Continent could provide, but Dixon had difficulty convincing consumers that Americans could make anything better than Europeans. Sales were slim until the Civil War, when pencils proved to be the writing instrument of choice among soldiers.

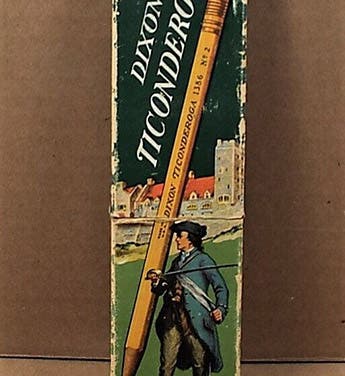

After the war, the Joseph Dixon Crucible company geared up to manufacture graphite pencils on a large scale, developing the tools needed to shape cedar blanks and a formula for the graphite "lead" for a pencil that would not easily break. Joseph died in 1869, several years before the Ticonderoga pencil made its official appearance, but it was an unqualified success, soon selling tens of millions of pencils annually. The original pencils were not painted; the now familiar yellow color was added in 1913 and the green and yellow ferrule even later. The name “Ticonderoga” was chosen because the graphite was now coming from a mine near Ticonderoga, New York, and because “Ticonderoga” was thought to be a distinctly American name (if we ignore the fact that the Fort was built by the French and named by the Iroquois).

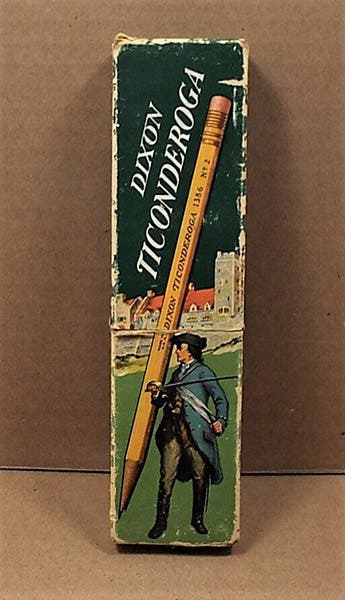

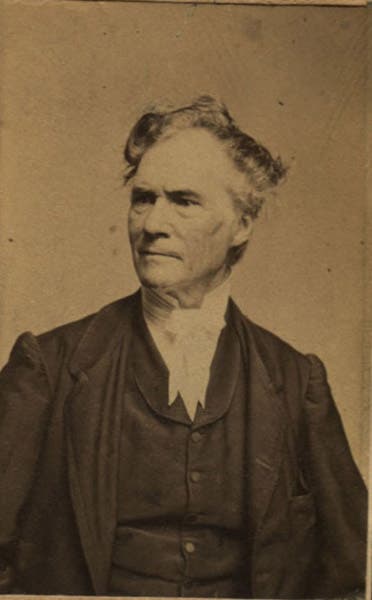

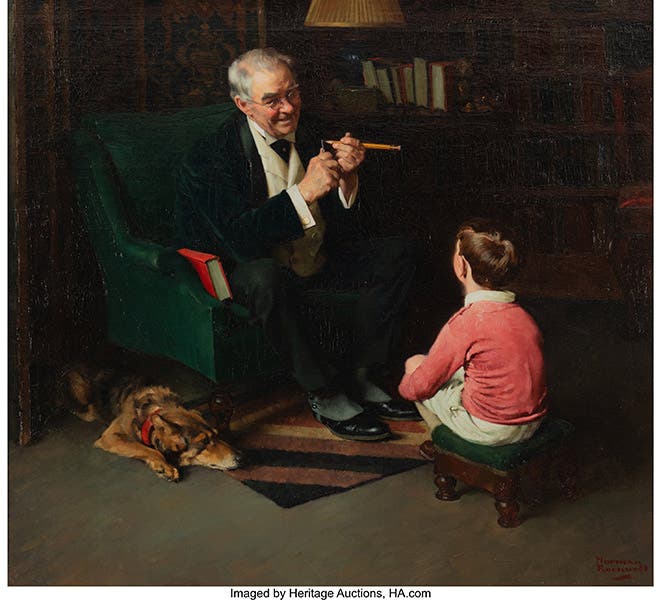

There is an undocumented portrait of Joseph Dixon in the Jersey City Free Public Library (second image), and smaller engraved portraits that appeared on various stock certificates over the years (third image). Since little else is known about Joseph, we will segue forwards to an interesting marketing event of the 1920s, and its disturbing aftermath in the 2020s. Sometime before 1926, the Joseph Dixon Crucible Company commissioned three paintings from young Norman Rockwell to use in its advertisements (Rockwell had recently begun painting covers for the Saturday Evening Post). Each painting featured one or more bright yellow Ticonderoga pencils. The first (I think) was called “His First Pencil” and featured a young lad selecting a yellow Ticonderoga from a helpful store owner. It appeared in an ad in Saturday Evening Post in August of 1926 (and perhaps earlier; fourth image). Another showed a grandfather sharpening a Ticonderoga for his grandson. By all accounts the advertisements were a great success.

The paintings remained with the company and were on display in the company headquarters, but in the mid-1970s, two of them were stolen. As far as I know they have never been recovered. In 2015, the now-named Dixon Ticonderoga Company, having moved its corporate headquarters to Heathrow, Florida, launched with great fanfare a corporate museum, containing some early Joseph Dixon machinery and lots of memorabilia, and showcasing the remaining Rockwell painting, “Grandfather and Grandson,” with the company president expressing the hope that this might lead to the return of the two missing paintings. There is even a video on YouTube commemorating the opening (and offering a view of “Grandfather and Grandson” as it was retrieved from storage).

But there was no fanfare when “Grandfather and Grandson” turned up on the auction block of Heritage Auctions in July of 2020, and was sold for $447,000, with no word of explanation anywhere (fifth image). So much for corporate historical consciousness. I do not know if the Dixon Ticonderoga Museum survived the disappearance of its centerpiece. I have been unable to find any local press reactions to the de-accessioning of this historic painting – one would think someone would have expressed just a little bit of outrage. All I know is that, until I find out more, I have bought my last Dixon Ticonderoga pencil, a pencil which, in a further slap at Joseph Dixon, is no longer made in America.

To end on an up-note, for those of you interested in learning more about the history of the pencil, I highly recommend The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance (1990), by Henry Petroski, a highly respected historian of technology. We have the book in our library’s open collections.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.