Scientist of the Day - Joseph Prestwich

Joseph Prestwich, an English geologist and archaeologist, was born Mar. 12, 1812. During the first 59 years of the 19th century, a number of people claimed to have found stone tools in rock layers that appeared to be very old, and had further argued that such tools were evidence of human antiquity, proof that humans had once shared the earth with animals that are now extinct. Such claimants included John Frere in England (1800), Philippe-Charles Schmerling in Belgium (1832), and Jacques Boucher de Perthes in France (1847). Conventional wisdom had humans being recent additions to the Earth, extending back some 6000 years at most, and the protestations of Frere and his few successors were almost unanimously rejected by even such open-minded geologists as Charles Lyell. The reason for such skepticism was in fact scientifically sound – it is very possible, when digging a ditch, for an object from an upper layer to fall down into a lower layer and appear to be much older than it really is. No one was going to accept the idea of human antiquity until an excavation was made that precluded such mishaps, and that was witnessed by more than just the one excavator.

In 1858, an amateur archaeologist in Devonshire, William Pengelly, found a cave in Brixham near Torquay that was unspoiled and had the potential, he thought, of yielding animal and perhaps human remains. Rather than plunge in with his pick-ax, Pengelly sent word to London and asked if any gentlemen geologists from the big city wanted to come down and take part in the excavation, and incidentally be witnesses if anything notable was unearthed. The Geological Society established an investigating committee, of which Prestwich was the treasurer, which went down to Brixham, where they dug through the cave floor and discovered not only fossil remains of cave bears, hyenas, and rhinos – animals now long gone from the British Isles – but also flaked stone tools among the bones, evidence that humans had been contemporaries of the extinct animal population. Prestwich began to think that perhaps claims for human antiquity needed to be reconsidered.

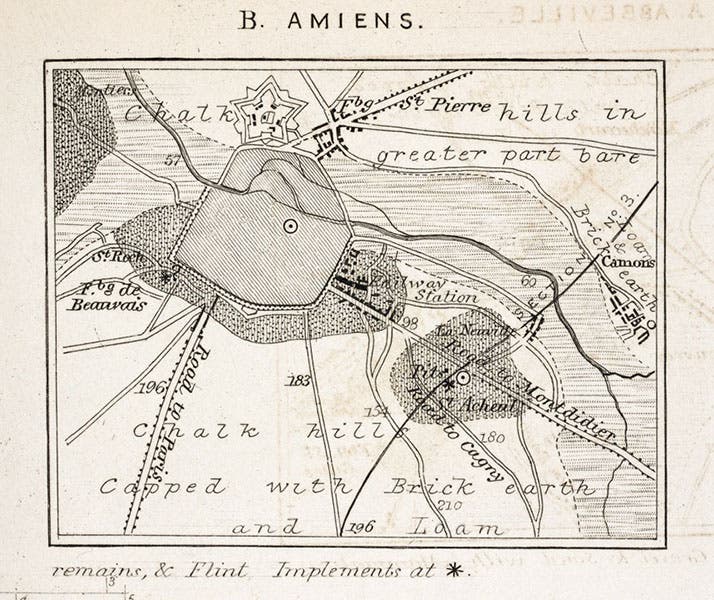

Map of Amiens, noting with an * (center right) the location of the hand-axe found in situ, detail of engraved plate accompanying Joseph Prestwich’s article in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 150, 1860; other maps on the same plate show sites in Abbeville and Hoxne (Linda Hall Library)

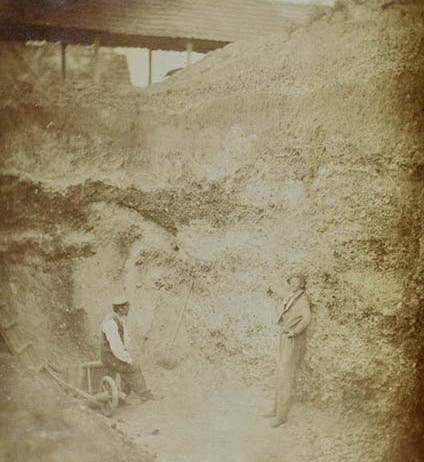

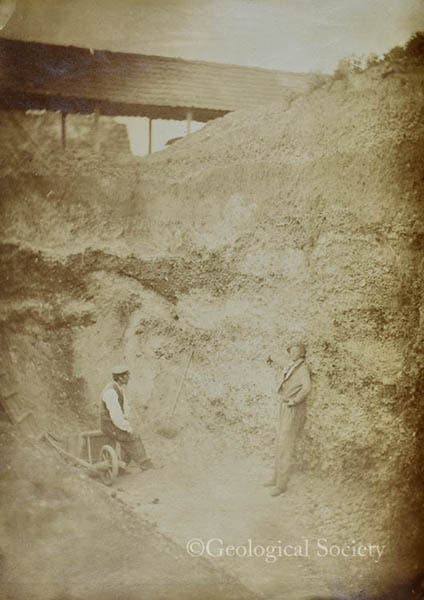

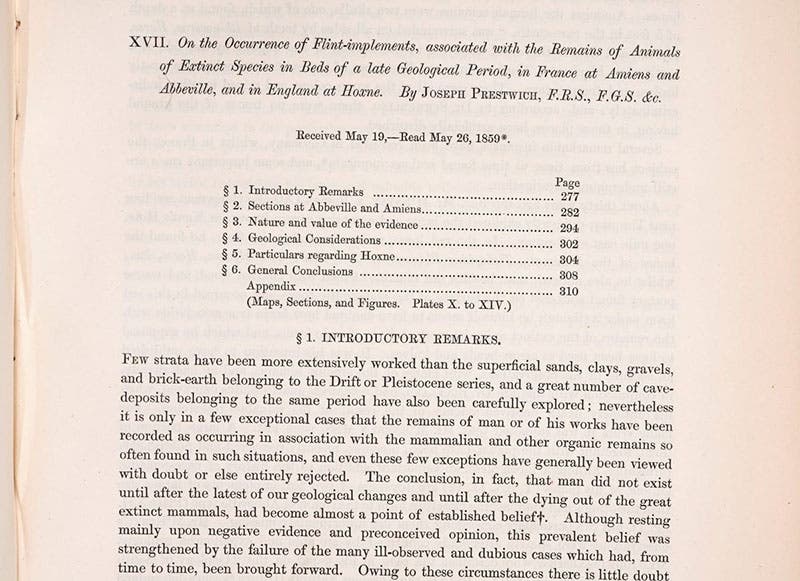

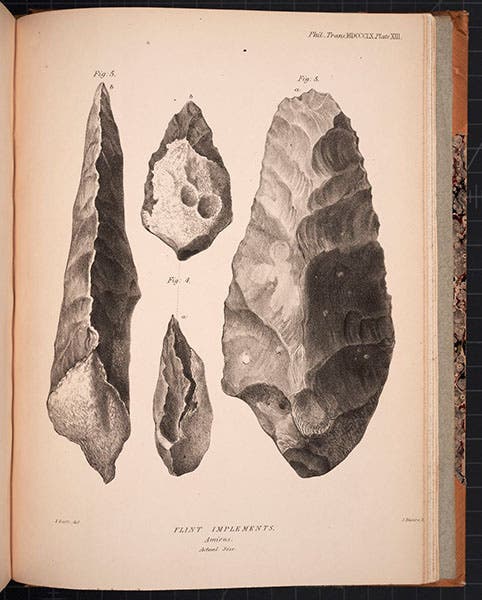

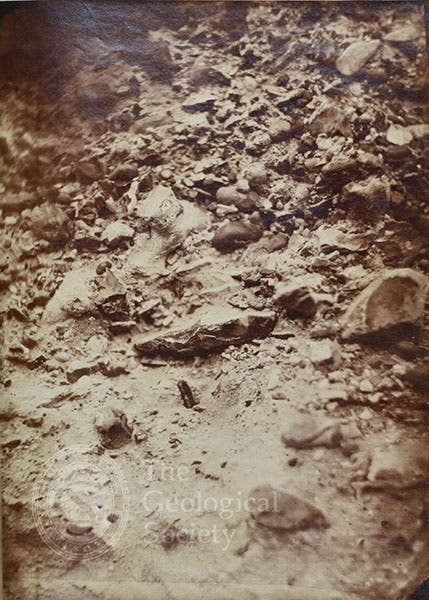

In the spring of the next year, 1859, Prestwich and a younger colleague, John Evans, went to northern France to meet Boucher de Perthes, who had found hundreds of stone tools in Abbeville over the course of 20 years but had convinced no one of their antiquity. Now he convinced Prestwich and Evans. While at Abbeville, they received a telegram informing them that a workman in a gravel pit at Saint-Acheul in Amiens, near Abbeville, had exposed a hand-axe in a pit wall, 11 feet below the earth's surface. Prestwich and Evans went there immediately, witnessed the axe still in situ, and someone had the presence of mind to call in a photographer to take a picture of the rock layers before the tool was extracted. The photograph was taken on this day, Apr. 27, 1859, and it turned out to be the best kind of witness (first image). Prestwich went back to the Royal Society and read a paper in May concerning the recent finds and declared that the debate about human antiquity was over – there was no longer any doubt that humans had lived on earth for a long, long time (fourth and fifth images). Six months later, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species. Seldom had one year seen two such important contributions to our understanding about the history of life on earth and our place in that history.

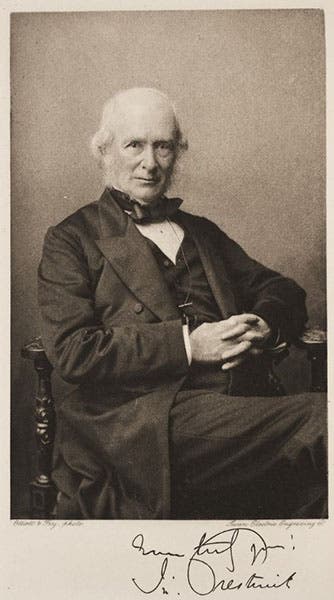

The excavations at Brixham cave took a long time, and work was complicated by the death in 1865 of Hugh Falconer, the London geologist who was in charge. Prestwich took over after Falconer’s death and finished the paper, which was finally published in the Philosophical Transactions in 1873, coming to the same conclusion – humans had been on this planet for a long time – as the 1860 paper on Amiens and Abbeville. We featured both of Prestwich’s papers in our 2012 exhibition, Blade and Bone: The Discovery of Human Antiquity (this link takes you to the Brixham paper; click "Next" to see the paper on Amiens). There are two portraits of Prestwich (from which we have selected one, second image) in his Life and Letters (1899), edited, as the title page declares, by “His Wife.” She did have a name, Lady Grace Anne Prestwich.

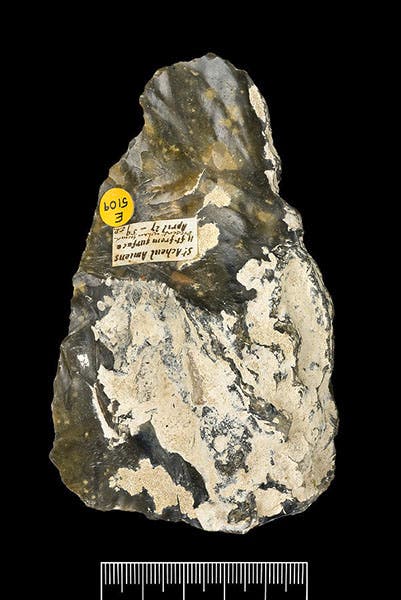

Hand-axe from Saint-Acheul, Amiens, found by Joseph Prestwich and John Evans on Apr. 27, 1859, with label, Natural History Museum, London (nhm.ac.uk)

![The label on a hand-axe from Saint-Acheul, Amiens: “St. Acheul Amiens/ 11 ft. from surface/ [entered later] present when found/ April 27 – 59 / J.P.”; Natural History Museum, London (nhm.ac.uk)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/ac49a03e-3698-4b5a-a7e0-94d687f22ae4/prestwich7.jpg?w=800&h=528&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

The label on a hand-axe from Saint-Acheul, Amiens: “St. Acheul Amiens/ 11 ft. from surface/ [entered later] present when found/ April 27 – 59 / J.P.”; Natural History Museum, London (nhm.ac.uk)

At least two copies of the April 27 photograph survive, one of which is in the archives of the Geological Society in London (first and eighth images). There is a stone hand-axe in the Natural History Museum with a paper sticker that claims that the tool was found Apr. 27, [18]59 at Saint-Acheul, 11 feet below the surface, and it is signed “J.P.”, for Joseph Prestwich (sixth and seventh images). Some years ago, I downloaded photos of the tool and the label from the Natural History Museum website; the photos have since disappeared from the site, so I hope it is okay to use them here. And I should point out that there is a similar hand-axe, in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, given to them by John Evans, with a paper label that makes the same claim of being the tool found and photographed on Apr. 27, 1859. You can see it at our post on Evans. Presumably both tools were found that day, and one of them is the tool sticking out of the sediment in the photograph.

A book about the Apr. 27 discovery and photograph was recently published: Making Deep History: Zeal, Perseverance, and the Time Revolution of 1859, by Clive Gamble (Oxford, 2021), which I was not able to consult, because our library has not yet acquired the book. I have, however, read most of Dr. Gamble’s published articles on the subject. If the text above needs to be corrected in the light of the new publication, I shall do so at the first opportunity.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.