Scientist of the Day - Jules Marcou

Jules Marcou, a French/American geologist, was born Apr. 20, 1824. in the Jura department of France. While recovering from health problems in Switzerland in the early 1840s, he met the glacier expert Louis Agassiz, who was quite impressed with Marcou and took him under his wing. Marcou first travelled to the United States in 1847, then returned when Agassiz moved to Harvard. Marcou spent the next five years dividing his time between France and the United States, and managed to travel quite a bit, to the mining regions around the Great Lakes and along the east coast, studying the stratigraphy of the places he visited. In 1853, he would cross the United States in the company of one of the Pacific Railroad Surveys.

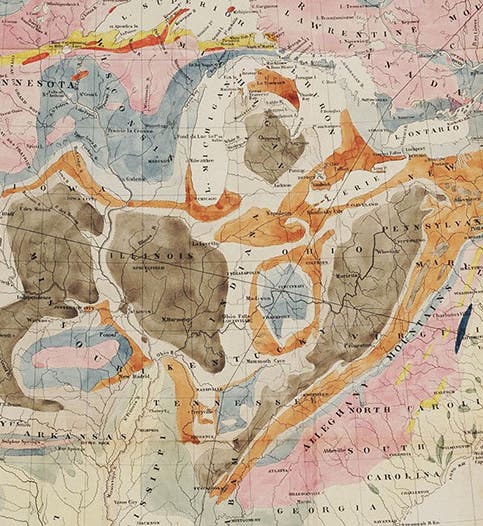

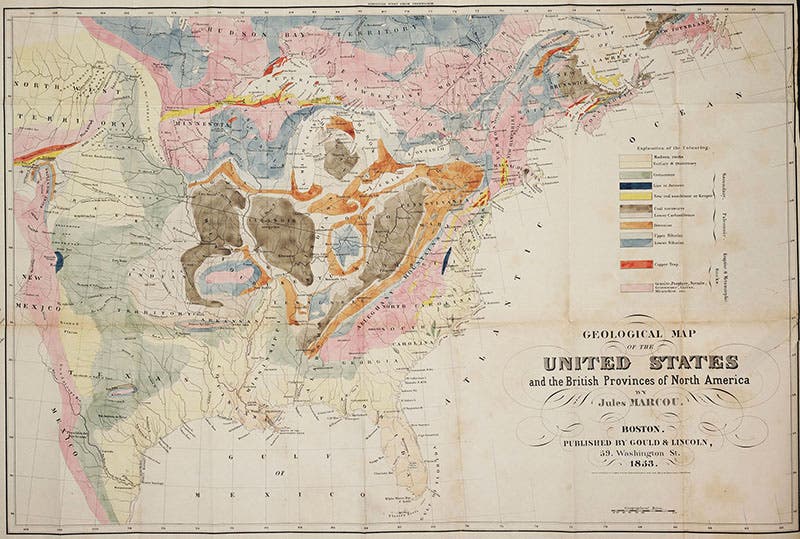

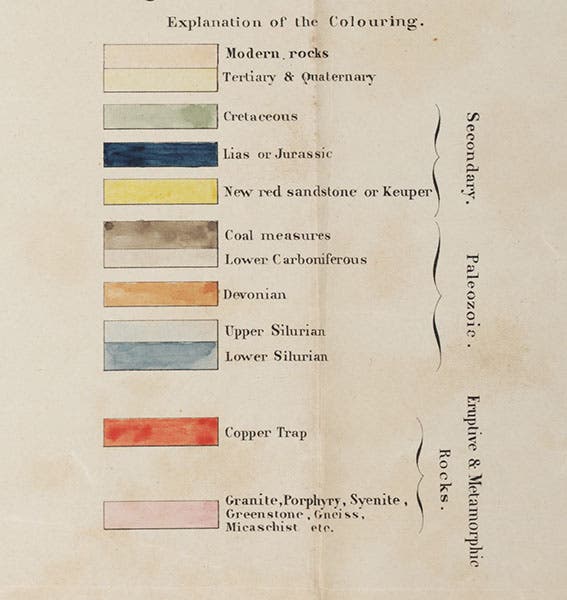

Also in 1853, he published A Geological Map of the United States of America, which is in fact a book, with a foldout geological map. The color coding indicates the surface rocks, whether Cretaceous, Jurassic, Carboniferous, etc. It is quite a lovely map, and very scarce in the 1853 edition, and it is why we are writing this post, so we have a reason to display the map and some details.

It is not clear whether Marcou made his cross-country trip before or after he produced his cross-country map – we are inclined, given the time constraints, to think he made the map first, which means he was mapping a country that by and large he had not seen. He does state in the introduction that he has relied heavily on the work of others, which must certainly have been the case.

American geologists like New Yorker James Hall (whom Marcou specifically thanked in the introduction) were outraged by Marcou's map, no doubt considering it preposterous that a young Frenchman with very little knowledge of America should have the effrontery to produce a map of the entire continent. They also did not appreciate the fact that Marcou often corrected American geologists in identifying the surface formations. And it certainly did not make things better when Marcou republished the map in two French journals in 1855 and then published a second edition of the book in 1858. We have all four versions of the map in our Library, but show here only images from the first edition of 1853. A comparison of a detail of the New England area, with the Connecticut River valley colored yellow (fifth image, above), to the key for the color coding (sixth image, below), tells us that Marcou thought that the area was of Triassic (Keuper) age. In this, Marcou was quite correct. He also designated the Kansas City area as upper Carboniferous, or Pennsylvanian. In this too he was correct. So whatever Hall thought, Marcou got some things right on his map.

In the introduction to his book, Marcou thanked Charles Lyell, who had published a geological map of the United States in his Travels in North America (1845). He also thanked Edouard de Verneuil, a French geologist who had made a geological tour of Russia with Roderick Murchison and then came to the United States in 1847, where he successfully correlated the rock formations of this country with those of France, England, Germany, and Russia, at least in Marcou's opinion. We mention this because the copy of Marcou’s 1853 book in our library was once Verneuil's copy, presented to him by Marcou, with the presentation inscription still intact. We acquired our copy from Daniel Crouch Rare Books in 2018.

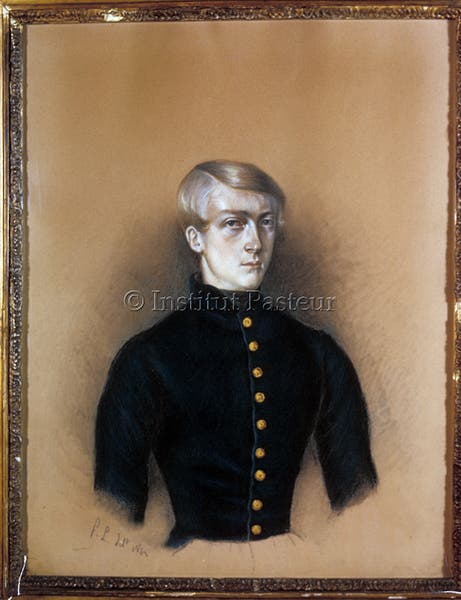

Marcou ultimately stayed in the U.S. for good, helping Agassiz establish the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard and working there for the rest of his days. Most of the surviving portraits show him as a veteran bearded naturalist, such as the carte de visite we show above (second image). But there is one notable exception – a pastel painted in 1842, when he was just 18 years old and a student in Paris (seventh image). The pastelist was a tutor who was only two years older. His name was Louis Pasteur. The painting is held by the Institut Pasteur.

Marcou died in 1898 and was buried, with Agassiz and many of their colleagues, past, present, and future, in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Mass. The monument on Marcou’s tomb certainly does stand out (eighth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.