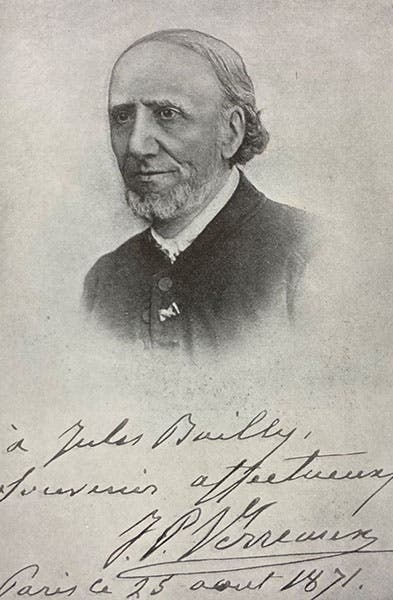

Scientist of the Day - Jules Verreaux

Jules Pierre Verreaux, a French naturalist and collector, was born Aug. 24, 1807. Verreaux's father, Jacques Philippe, had founded a natural history firm, the Maison Verreaux, in 1803 in Paris, the first firm to market items of natural history to collectors and museums. Jules went to work for the family firm at a young age, travelling to South Africa when he was still in his teens, and he continued to travel for the rest of his life. HIs two brothers were also part of the firm, but Jules seems to have played the leading role in the expansion of the Maison Verreaux, which suppled specimens to museums all over the world, but especially to the Museum of Natural History in Paris.

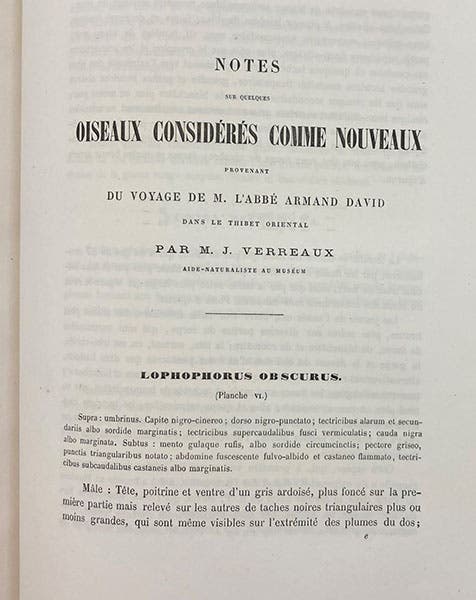

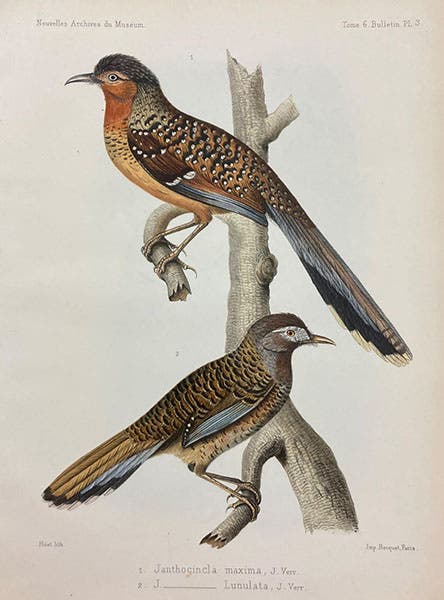

Jules travelled extensively and collected heavily in Australia and Africa, and to a lesser extent in China. I don't know whether, while in China, he met Père Armand David, the French missionary who discovered the panda (and Père David's deer), but when Father David sent specimens back to the Museum of Natural History, it was Verreaux who ended up with the birds, his particular speciality, and he published (and named) many of David’s discoveries in the pages of the Nouvelles archives of the Museum, a series we have in our library. We show several plates here, lithographed after drawings by Josephe Hüet, that were published along with Verreaux's descriptions, in this series (first and fourth images).

Ianthocincla lunulata and I. maxima, two barred laughingthrushes, found by Père Armand David in Chinese Tibet, described and named by Jules Verreaux, lithograph after drawing by Josephe Hüet, in Bulletin des nouvelles archives du Muséum, vol. 6, 1870 (Linda Hall Library)

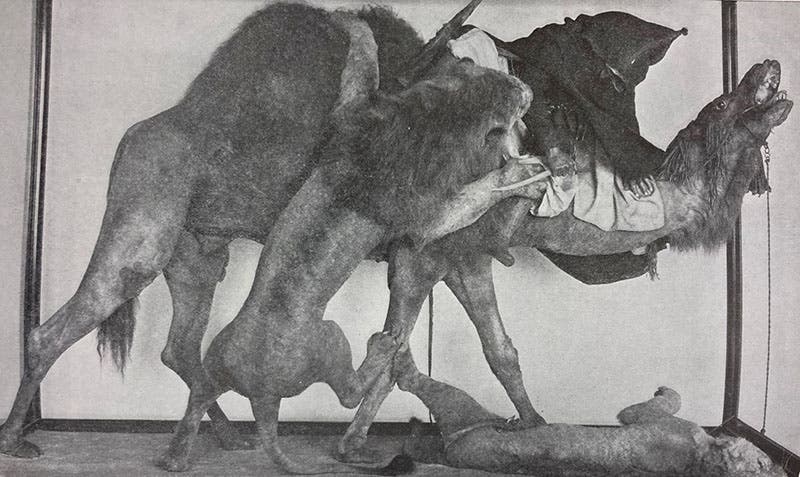

It seems that Maison Verreaux sold not only individual specimens, but animal groups, which would become increasingly popular with museums as a way of attracting the attention of visitors. One of Jules’ creations, which he fashioned for the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1867, showed a camel and its driver being attacked by Barbary lions. The newly formed American Museum of Natural History in New York City bought the group in 1869, I believe its first purchase of this kind, and then later passed it on to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, where it still resides. Our photograph (with the camel-driver’s head discretely obscured) comes from the pages of the American Museum Journal of 1914, part of an article where Verreaux was praised for inventing the animal group and inspiring later diorama designers. The article also mentioned that Henry Augustus Ward was motivated by the example of Verreaux to found his own natural history supply firm, Ward's Natural Science Establishment, which did for U.S. museums what the Maison Verreaux provided for European museums.

Verreaux, when he was young, was also involved in a mount that later became quite controversial, that of an African bushman from Botswana. Jules observed a burial there and stole the fresh corpse from the grave, sending the skin and skull back to Paris, where his brothers applied their taxidermy skills to create a museum mount. While such a feat of taxidermy would never be tolerated now, it was not uncommon in the 1830s and 1840s to treat human specimens just like animal specimens and put them on display in museums. The really shocking thing about El Negro, as the mount was called, is that it was sold to a Spanish Museum and continued to be on display right up until the 1990s, when an accrual of outraged protests led to the removal of the exhibit; El Negro was then returned to Botswana for reburial. Even though Verreaux was only 23 when he robbed the grave, his participation has always been a blemish on his professional reputation.

Where Jules Verreaux really excelled was in the field of eponymy. He has an amazing number of animals and birds named after him, some that he discovered, and some that were simply named for him in tribute by grateful museum zoologists and ornithologists. I chose several of the more photogenic to include here: Verreaux’s eagle, a handsome black eagle from Africa (sixth image), and the Southern Conger eel (Conger verreauxi), found in various reefs in the Indian and Pacific Oceans (seventh image). If those are not enough, you could seek out: Verreaux’s sifaka, from Madagascar; Verreaux’s eagle-owl of sub-Saharan Africa, and Verreaux’s tree frog, from Australia. There are more, but you will have to find those on your own.

Verreaux died on Sep. 7, 1873, in England, where he had fled during the Siege of Paris in 1870. I was unable to discover where he was buried and if he has a memorial stone. I know only that his remains never made it back to their natural resting place in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.