Scientist of the Day - Julien Fraipont

Julien Fraipont, a Belgian paleontologist with an interest in anthropology, was born Aug. 17, 1857. In the early 1880s, many anthropologists believed that the original Neanderthal specimen discovered in 1856 by Johann Carl Fuhlrott, and described by Hermann Schaafhausen, was a pathological oddity and did not represent an ancient race of humans. Critics of Neanderthal as a human type argued that all of its aberrant features – long skull, thick brow ridges, sloping forehead, curved thigh bones – could be explained as the byproducts of disease or occupation. One other Neanderthal-like skull had been discovered in Gibraltar back in 1848, and it was interpreted as Neanderthal by George Busk in England in 1864, but very few archaeologists were buying the possibility of there having been a race of "Neanderthal men."

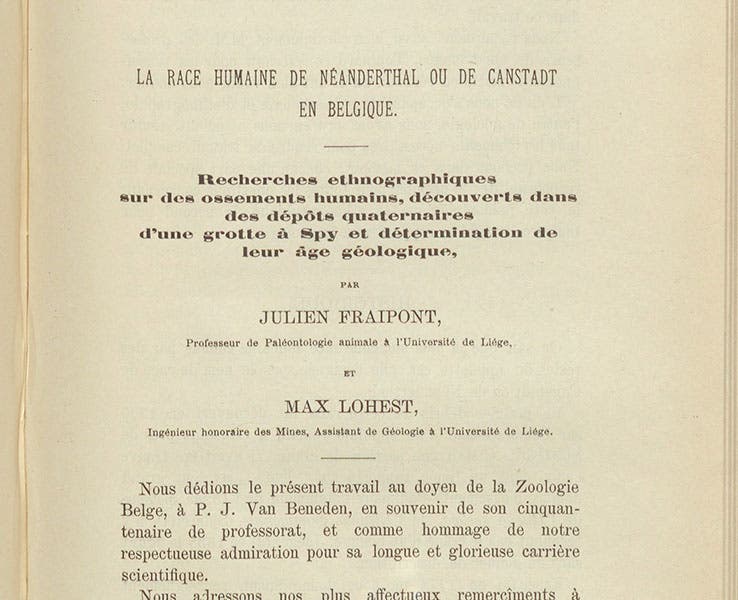

Then, in 1886, two skeletons, a male and a female, were found in a cave in Spy, in the province of Namur in Belgium. The female is referred to as Spy 1, the male as Spy 2. The Spy cave is about 40 miles southeast of Brussels and 45 miles west of Liège. The discoveries were made by Marcel de Puydt, an archaeologist, and Max Lohest, a geologist. Fraipont was the expert on human anatomy and fossils who was brought in to figure out what had been unearthed. All three men taught at the University of Liège. The bones, and especially the skulls, of the Spy specimens were remarkably similar to the remains of the original Neanderthal specimen. Fraipoint was convinced by the evidence that the Spy individuals were ancient, and that they were Neanderthal, and he and Lohest teamed up to write a paper announcing the finds and arguing for their antiquity and Neanderthal status. The paper was titled (we translate from the French): "The human race of Neanderthal or Canstadt in Belgium: Ethnographic research on human bones, discovered in quaternary deposits in a cave at Spy, and a determination of their geological age" (the Canstadt skull was a skull found in Germany in 1700 that some French authors lumped in with Neanderthal in the late 1870s, but it later turned out to be a recent skull, probably of Roman age).

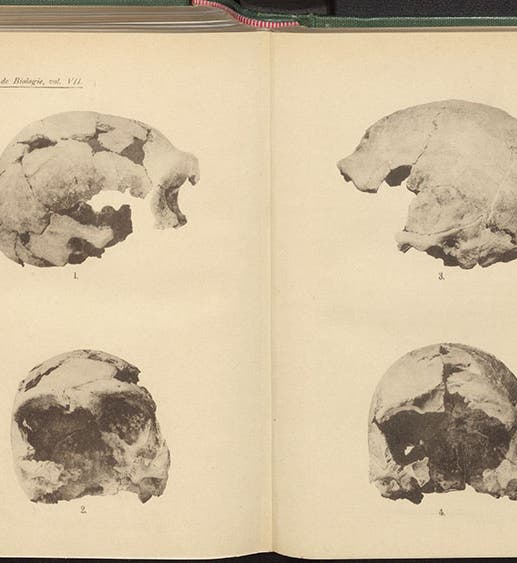

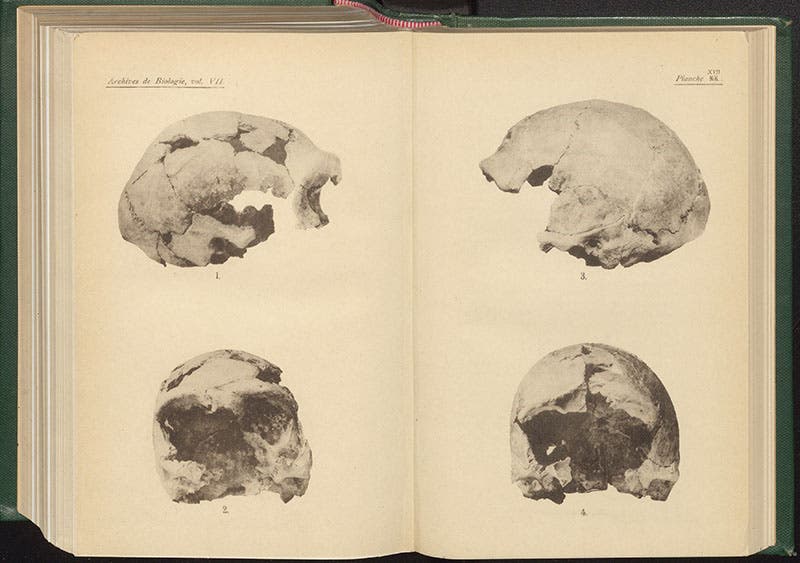

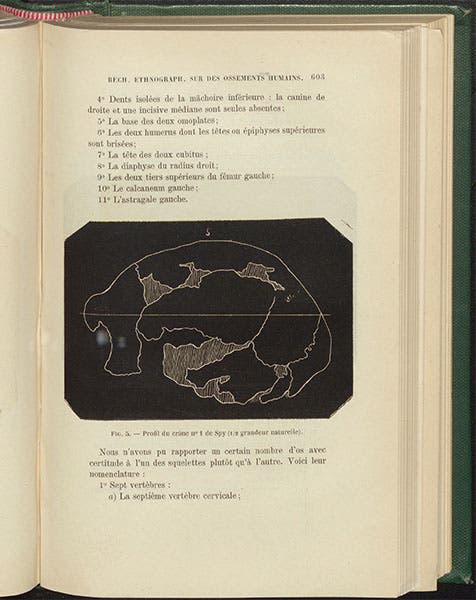

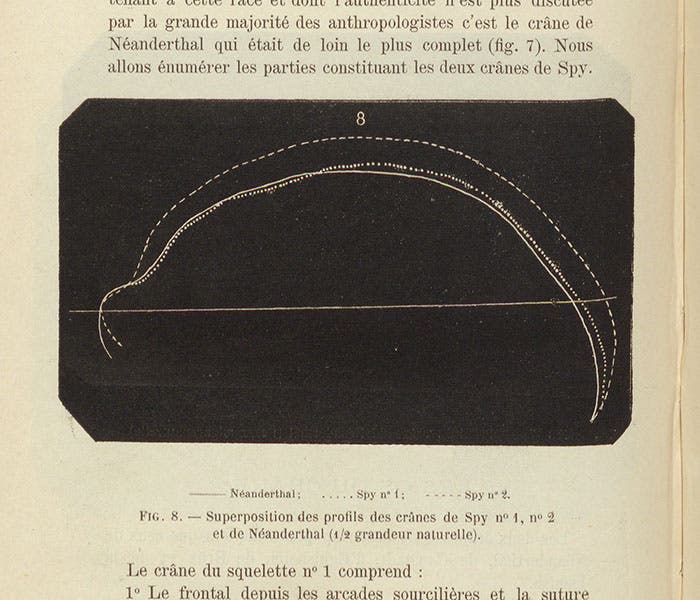

Fraipont's and Lohest's article, really a monograph, appeared in volume 7 (1887) of the Archives de Biologie, which we have here at the Library. It is illustrated with multiple white-on-black line drawings showing the skulls of Spy 1 and Spy 2 from the top, sides, front, and back - we show one of those here (fourth image). There is also a side-view comparison of the skulls of Spy 1, Spy 2, and Neanderthal, which reveals their great similarities (fifth image). And there are four double-page plates of photographs of the skulls and the major limb bones – we show one of those here as well (first image).

Fraipont was adamant that the Spy discoveries, and the geological strata in which they were found, demonstrated that Neanderthal was truly ancient and was a valid human type, and he took the offensive against the critics of Neanderthal's antiquity. In fact, he was the principal defender of Neanderthal from 1887 to 1908, when three more Neanderthal skeletons were discovered in three different sites in France, and Fraipont's conclusions were confirmed.

We displayed Fraipont's and Lohest's article in our 2012 rare-book exhibition, Blade and Bone: The Discovery of Human Antiquity. You may see the exhibition catalog page on Spy here. In you are interested, we also displayed the two original Neanderthal papers by Fuhlrott and Schaafhausen, and Marcellin Boule’s paper on the most famous of the 1908 French Neanderthal's, the Old Man of La Chapelle.

Wikipedia has a recent photograph of the Spy 2 skull with its article, but it has been a little too edited for my taste, so I don't include it here. Instead, I show a restoration of the Spy 2 Neanderthal, sculpted for the Natural History Museum in London by two very talented Dutch brothers who deserve to be better known (sixth image). The sculpture, out of the workshop of Adrie and Alfons Kennis, is full-size and free-standing, and is nude. So I don’t get into trouble for putting very realistic sculptures of naked men, even extinct ones, on the Library website, I show instead a detail of the face (which seems appropriate, since this post has been all about the Spy skulls), and provide you with a link to the full sculpture, should you want to view Spy 2 as the sculptors intended (the photograph is from Don’s Maps, an excellent anthropology resource). The face of Spy 2, as restored by the Kennis brothers, is rugged, prematurely aged, amazingly realistic – and utterly charming. If this isn't the finest restoration of an ancient human ever crafted, I would like to see the competition. I suspect every one of the contenders would be a Kennis and Kennis production. You can visit their website here.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.