Scientist of the Day - Karel Absolon

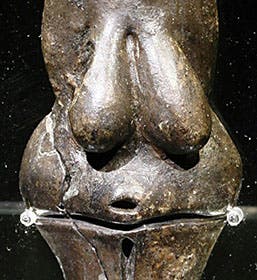

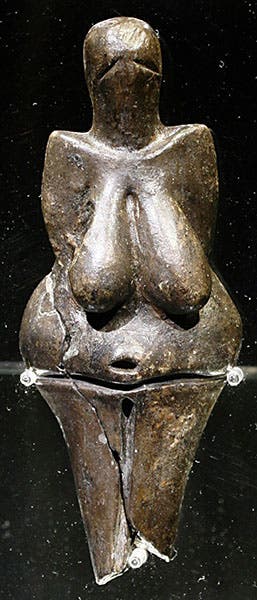

Karel Absolon, a Czech archaeologist, was born June 16, 1877. Absolon was curator of the Moravian Museum in Brno (the same city where Gregor Mendel lived and conducted his pea-hybrid experiments in the 1850-60s). In July of 1925, Absolon and his archaeological team discovered a Venus figurine at Dolní Věstonice, a site south of Brno, in what was then Moravia, and is now the Czech Republic (first image). The first Venus figurine had been found in 1864 (and was affectionately called the Venus impudique), and since then a number of others had been unearthed, each named after the place of discovery: the Venus of Menton (1880s), the Venus of Willendorf (1908), and the Venus of Lespughe (1922), to name and link to just a few.

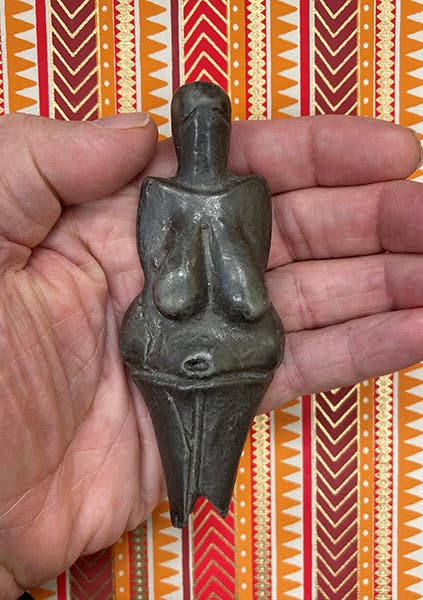

Venus figurines date from 25,000 to 31,000 years ago, from what is known as the Gravettian culture or Gravettian industry of Europe. They portray the female human form with enlarged breasts, hips, and belly, and were possibly used as fertility totems by Upper Paleolithic peoples. The Venus of Dolní Věstonice (pronounced Dohl-nee Ves-toe-NEE-zay) is distinguished in two ways: it was fashioned about 30-31,000 years ago, making it (with one exception) the oldest such figurine known, and it is ceramic, made of fired clay. This makes it the oldest piece of pottery in the world (although we should include under that rubric the many other pottery fragments found at Dolní Věstonice). In fact, it is the oldest example of a fired ceramic by about 10,000 years, so it is a rather remarkable object in many ways. It is kept in the same Museum in Brno where Absolon worked (third image), and they are so proud of their Venus that they hardly ever put her on display. The last time she made a public appearance was at an exhibition in Vienna in 2008. This seems like overly-protective behavior, rather like keeping the Mona Lisa in the vault all the time. This video will put you in her company for a short while, and it includes several maps that you may find useful, but except for the opening 20 seconds, most of the still photos are of replicas, not the original. You can always identify the original Venus of Dolní Věstonice, because she was broken in two when discovered, and is held together by a delicate nylon monofilament. The replicas are all in one piece. I own a replica (sixth image, below). I should perhaps wrap a piece of fishline around her middle and see who notices.

You may have noticed that, except for the video, all of the image links in this post, and three of the images we show here, come from the same site, Don’s Maps. I could have used the images from Wikipedia, which has an article on each of the Venus figurines mentioned here, but I thought Don’s Maps deserved mention, and besides, the images there are better. Here is the page on the Venus of Dolní Věstonice. Don Hitchcock is a retired Australian schoolteacher and amateur archaeologist whom I have never met, but his website. which he runs and maintains all by himself, is a terrific resource on matters archaeological. As far as I can tell, he has been everywhere in Europe, camera in hand, so that many of the photos on his website are his, but just as many of the images shown are ones that he has culled from elsewhere on the web or from printed sources. If you would like to know more about Venus figurines, here is his master page, with well over 80 entries. Click on any one, and you will be taken to a page on that particular Venus, with a bevy of images and factually accurate text. And there is no glitz whatsoever, except for the inherent splendor of the displayed objects. And no ads!

Three years ago, on this date in 2020, I wrote a version of this notice, but the Library, under its COVID 19 protocol, had pared the Scientist of the Day down to three posts a week, and this post was not published. So I sent it out as an email to a subscription list I have, and I also sent it to Don Hitchcock, so that he would know that someone was talking about him. I received a long, chatty letter back, in which he explained how the website evolved and how and why it is different from more conventional archaeological websites, mainly in providing information that is intelligible to a lay audience, and yet fully supplied with sources and references, especially for all the images. I liked him immediately, since we have exactly the same goals in our public outreach. He also mentioned that when he was in Brno, his spoken English and French, and his wife’s German, were of no use whatsoever – it was Czech or nothing. Remember that, if you go visit the Brno Museum. One would think that the 100th anniversary of the discovery of the Venus of Dolní Věstonice, on July 13, 2025, would bring the ceramic Venus out of hiding and into the public eye once again.

Actual-size replica of the Venus of Dolní Věstonice, author’s collection (photo by the author)

Don’s Maps has been on the web for nearly 30 years, and it is still actively maintained by Don, as you will see if you look at this page on recent additions and changes, with the latest entry being made just last month. You can also see a photo of Don on top of the Musée de l'Homme in Paris.

And should you like to follow Don on one of his many bike trips, or learn how to explore the Australian bush on foot, or even how to build mortared stone walls in the Australian outback, you can do that as well. Don’s Maps is one of the great old-school internet resources. May it stay in place for a long, long time!

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.