Scientist of the Day - Katsushika Hokusai

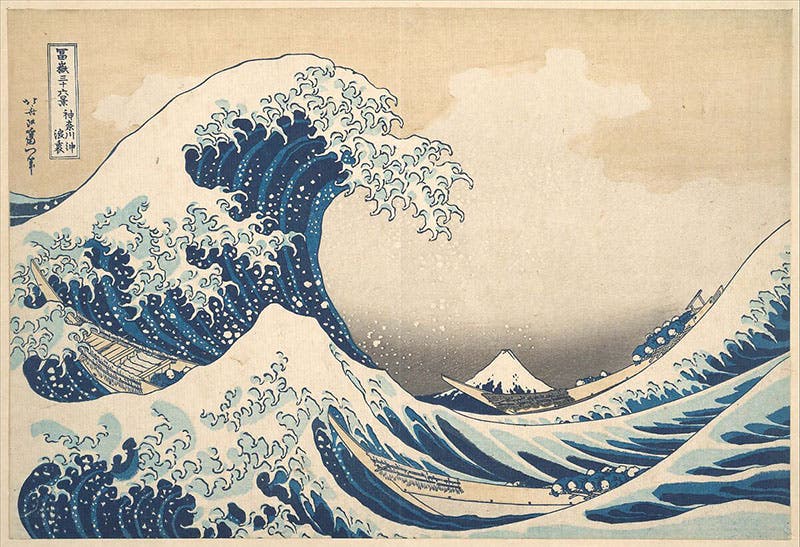

Katsushika Hokusai, a Japanese painter, was born Oct. 31, 1760. Hokusai lived during the late Edo period in what is now Tokyo, and although he painted in many different styles, he is best known in the West for his woodcuts, printed in color. And to be more specific, he is best known for a single series of woodcuts, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (1830-32). One woodcut from that series, Great Wave off Kanazawa (third image), may be the most recognizable non-western work of art in the modern world.

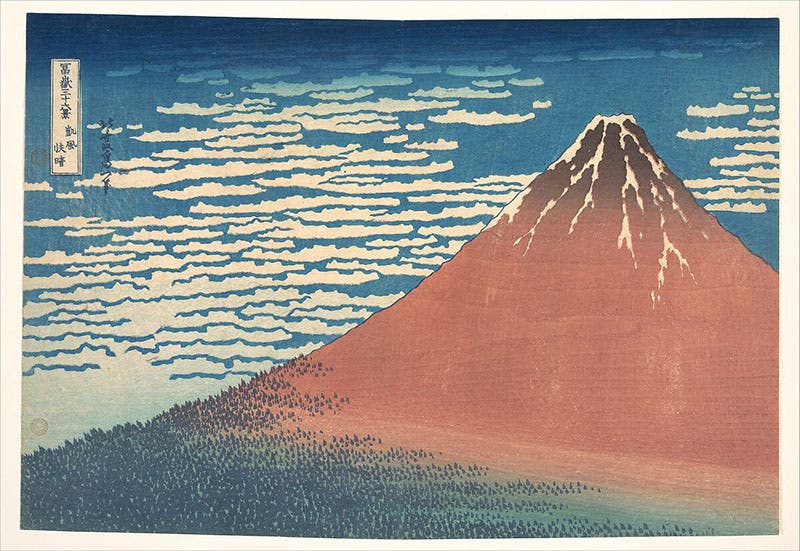

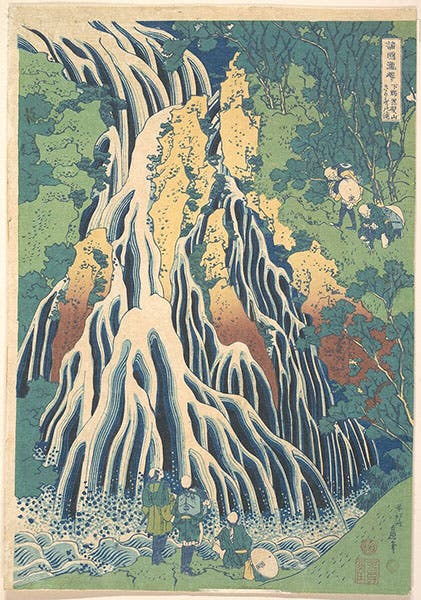

I have no business writing about Hokusai, since I know very little about him or about Japanese art of his era. But every time I see the Great Wave or Red Fuji or one of the prints in A Tour of Japanese Waterfalls (fourth image), I think, there must be a lesson here for historians of science. We often attempt to connect scientific vision with artistic vision, as when we argue that the 17th-century Dutch interest in the minutiae of still life painting might have turned Northern European natural philosophers toward the experimental investigation of nature, or when we attempt to connect the rise of Romanticism in the early 19th century with the growing popularity of natural history and geology.

Yet when we look at Hokusai’s fisherman (Kajikazawa in Kai Province, first image), which was printed about the time, 1830-32, that Charles Lyell was publishing his masterpiece on uniformitarian geology and Charles Darwin was recording his adventures on HMS Beagle, we have to admit that Hokusai saw the world differently. There is no way in the world that a European in 1830 could have made that woodcut. If they had, would it have changed the way scientists saw the world?

We think we see the same world as everyone else, that there is an objective reality out there, available to all. But Hokusai teaches us that we are conditioned to see the world a certain way, by our upbringing and intellectual heritage, and it is extremely difficult to see things a new way. Everyone agrees, when they see a Hokusai print for the first time, that it is beautiful and elegant, and provides a paragon worth emulating, yet no one in the west ever thought to paint the world that way. Why is that?

In the history of science, there are many examples of what can happen when you look at the world in a new way. In the 16th century, physicists observed a projectile and saw an object moving unnaturally and wanting to stop. Galileo saw a moving object as in a natural state, with no inclination to stop, and its natural tendency to keep going – its inertia – became the cornerstone of a new physics. Albert Einstein wondered, what if the speed of light were the same for all observers, no matter how they were moving relative to one another? From this question emerged the special theory of relativity in 1905. Many paradigm shifts in the history of science are the result of looking at phenomena in a new way, or from a novel vantage point. What we do not have is a general recipe for doing that. Perhaps if we can understand why no one saw the world like Hokusai until Hokusai, we might be one step closer to understanding the origin of true innovation in science, or in any other endeavor.

That's not much of a contribution to the philosophy of science, or the study of innovation, which is why, I suppose, that I am a historian. But it does provide me with an opportunity to adorn this post with 6 glorious woodcuts, which ought to make your day brighter, and perhaps inspire you to do at least one thing differently today, and so celebrate the birthday of the great Hokusai.

My thanks to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for making their Hokusai prints available online. They are all original prints, 1830-32, unlike most of the prints on Wikimedia commons.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.