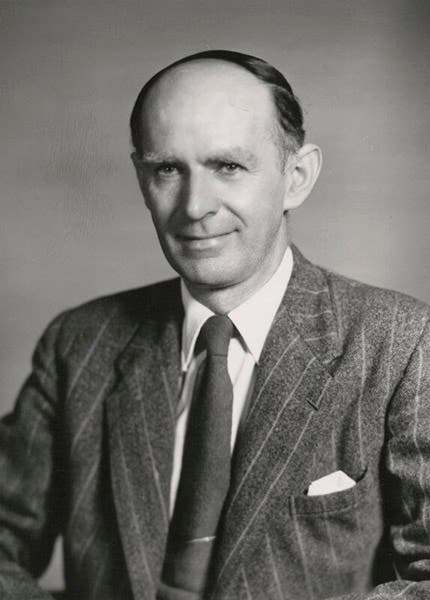

Scientist of the Day - Kenneth Oakley

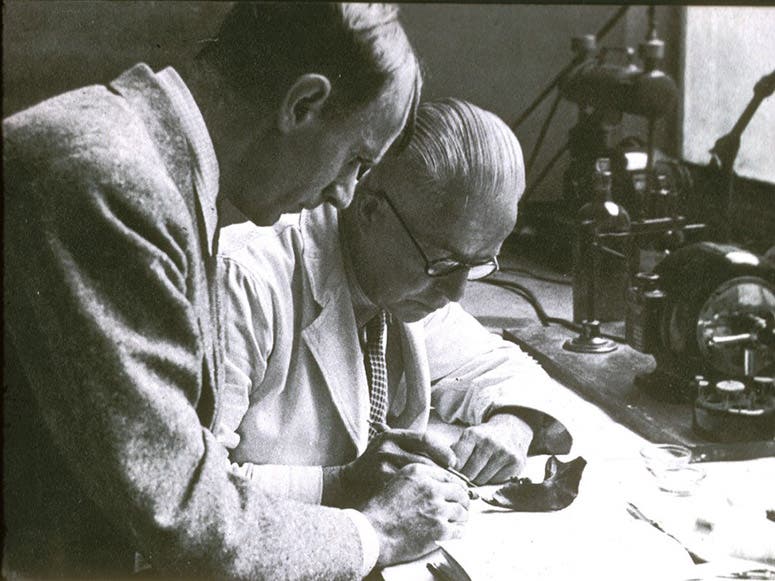

Kenneth P. Oakley (left) in the lab with the Piltdown I mandible at the British Museum (Natural History), 1953, Natural History Museum (nhm.ac.uk)

Kenneth Oakley, an English anthropologist, died Nov. 2, 1981, at the age of 70. In 1953, Oakley was one of the three key figures involved in proving that Piltdown man was a fake.

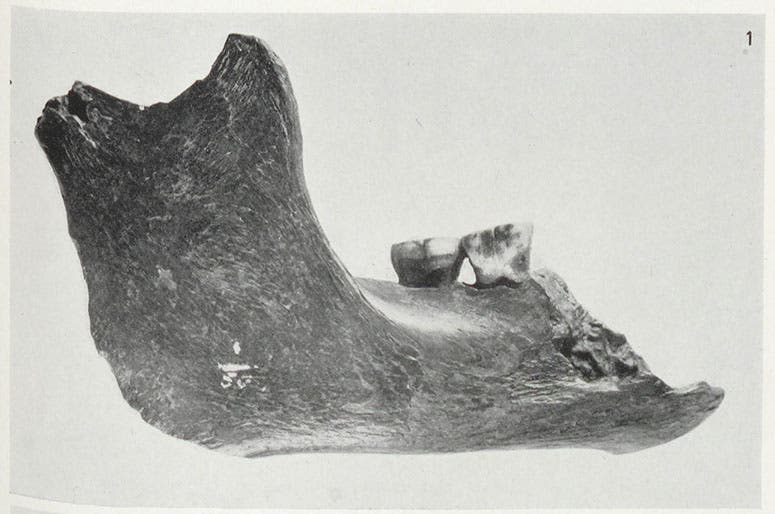

The Piltdown fragments – a mandible (lower jaw) with two molars intact, several pieces of skull, a canine, and a few other fragments (see second image) – had been found in 1912 by an amateur archaeologist, Charles Dawson, at a gravel pit in Piltdown, England, and had been described and named by a distinguished anthropologist, Arthur Smith Woodward, in 1913. Eoanthropus dawsonii, as the specimen was scientifically labeled, took his place as the ancestral Englishman. Additional fragments (Piltdown II) were found by Dawson in 1915. Piltdown man, as he was called in the popular press, was somewhat problematic, as he had an apelike jaw but a large braincase, unlike Java man, which had a small brain but a more human-like jaw (see our post on Eugene Dubois). It was hard to see how Piltdown man and Java Man fit into the same family tree. But room was found for Piltdown nevertheless. You may find more details about the Piltdown discovery, and some images of the fossils and various reconstructions, in our posts on Dawson, Woodward, and Arthur Keith, another anthropologist who supported the antiquity of Piltdown man.

In the 1940s, Oakley was working in the anthropological lab at the British Museum (Natural History), where Woodward had worked until his death in 1944. The Piltdown fragments were kept there in the Museum. By 1947, Oakley had perfected a dating technique known as fluorine absorption dating. When a bone is buried in the ground, it absorbs fluorine from the soil, and the amount of fluorine in the bone is a measure of how long it has been buried. The method had been invented back in the 1890s but had not been used successfully before Oakley. The problem is that the fluorine uptake varies from location to location, so that two bones from different sites might have the same amount of fluorine but be of different ages. But Oakley showed that for a given location, bones with higher amounts of fluorine were demonstrably older than bones from the same site with lower amounts. We might mention that radiocarbon dating was not discovered /invented until 1949 and was not utilized in the field until the mid-1950s; see our post on Willard Libby.

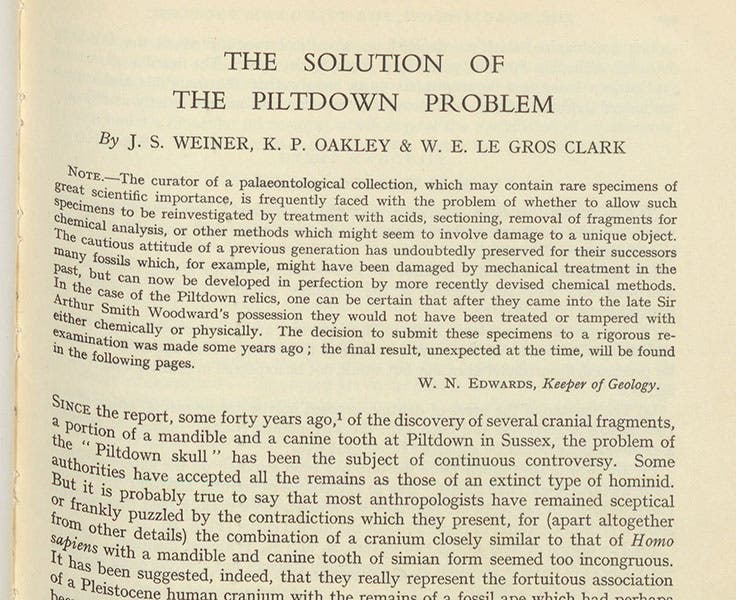

Detail of the first paragraph of "The solution to the Piltdown problem,” by Joseph S. Weiner, Kenneth P. Oakley, Wilfrid Le Gros Clark, Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Geology, vol. 2, 1953 (Linda Hall Library)

Oakley first applied his fluorine dating in 1948 to two recently discovered anthropological specimens, Swanscombe Man and the Galley Hill skeleton, both thought to be of Middle Pleistocene age, or some hundreds of thousands of years old. The Swanscombe bones had a fluorine content of some 2%, which was a lot, so they were indeed old, while the Galley Hill skeleton had only a fraction of a percent, indicating that it was a later burial that had been intruded into an older layer of sediment. So the technique worked.

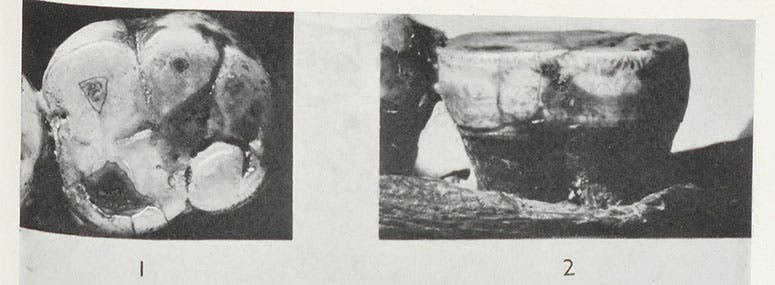

The Piltdown I mandible, with two molars intact, photograph, plate in "The solution to the Piltdown problem,” by Joseph S. Weiner, Kenneth P. Oakley, Wilfrid Le Gros Clark, Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Geology, vol. 2, 1953 (Linda Hall Library)

In 1949, Oakley was given permission to test the Piltdown fragments, as some had suspected that the skull fragments and the jawbone were of different ages. Oakley found that they had the same level of fluorine, so they were of approximately the same age. That level was low for both of them, but Oakley at the time did not have other specimens from the same site – animal bones, for example – with which to compare them, so he did not realize the significance of the low levels.

The two embedded molars in the Piltdown I mandible, which were found to have been filed into their present shape, detail of plate in "The solution to the Piltdown problem,” by Joseph S. Weiner, Kenneth P. Oakley, Wilfrid Le Gros Clark, Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Geology, vol. 2, 1953 (Linda Hall Library)

In 1953, at a conference in London, an anthropologist from Oxford, Joseph Weiner, who worked in the lab of Wilfrid Le Gros Clark, saw the Piltdown fragments for the first time, and met Oakley, and was surprised to learn that the so-called Piltdown II fragments, found by Dawson in 1915, came from an unknown and undocumented location, which to Weiner, undermined their credibility as valid fossils. His suspicions raised, he convinced Le Gros Clark that they should approach Oakley and ask him to repeat his fluorine tests, at the same time looking for other evidence that might be suspicious concerning the Piltdown fragments. Oakley, with the backing of the British Museum, agreed, and Oakley found that not only were the Piltdown fragments of very recent age – 500 to 1000 years instead of 500,000 – but there was microscopic evidence that the molars and the canine had been filed down, and the wear on the molars was not at all what one would expect from teeth that had been used in a human mouth. Moreover, when he drilled into the old-looking jaw, the bone beneath the surface was white, as if the surface had not aged naturally, but had been dyed. The results were conclusive: the Piltdown jaw was an orangutan jaw, with the teeth filed down to resemble human teeth, and the skull fragments, while thicker than normal, were nevertheless those of a recent human, from medieval times, stained to look old. Piltdown man was a fake, or a fraud, or a hoax – all three words have been used. The results were published in the Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Geology in 1953, picked up by Time magazine that same month (November), and Piltdown was summarily removed from his place in the annals of human ancestors (see third, fourth, and fifth images)

The person who perpetrated the hoax was unknown at the time, and lots of individuals were considered as suspects, but the consensus now is that Charles Dawson and Dawson alone perpetrated the fraud, hoping to become famous enough to be elected to the Royal Society of London. As Dawson died in 1916, he fortunately never attained that honor.

Oakley was a somewhat reluctant participant in the unmasking of Piltdown man, as it meant casting a shadow over the career of his esteemed mentor at the Museum, Arthur Smith Woodward. It is to his credit that Oakley was able to carry though in spite of his affection for his recently deceased colleague. Oakley went on to write several popular books on human antiquity. Our last image shows him in 1957, at age 46, looking fairly much at peace with the world.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.