Scientist of the Day - Krafft Ehricke

Krafft Arnold Ehricke, a German-American rocket engineer, was born Mar. 24, 1917, in Berlin. Ehricke became a rocket enthusiast when he was just a lad, entering his teens as the first German Rocket society was founded in Berlin in 1927, from whose ranks he was excluded by his youth. He remembered being very much taken by Fritz Lang’s seminal film, Die Frau im Mond (1929), about a rocket flight to the moon, which he saw many times. Ehricke received a degree in aeronautical engineering from the Technical University of Berlin, but his interest in space flight was cut short by the onset of World War II. He spent 3 years at the Russian front, and, amazingly, survived, although he was wounded twice. But his interest in rocketry was well known, especially to Wehrner von Braun, and he was eventually spirited out of the infantry in 1942 by von Braun and into the rocket group at Peenemünde, where the V-1 and V-2 rockets where being developed, and where he served as a rocket propulsion engineer until 1945.

Even before the war in Germany ended in May of 1945, the U.S. military had developed a plan to round up the most promising German rocket engineers and invite them to the United States before the Soviets got to them and hauled them back to Russia. Operation Paperclip, as it was called, managed to snag von Braun and most of the Peenemünde group, but Ehricke slipped through their net when he furtively returned to Berlin to join his wife. For over a year, he hid whenever there was a knock at the door, fearful that Russia had come calling. Then, one day in 1947, an American officer came knocking, the door was answered, and Ehricke ended up belatedly joining Operation Paperclip. He was sent, like thousands of other engineers and their families, to Fort Bliss, Texas, there to be gradually assimilated into the American rocket workforce.

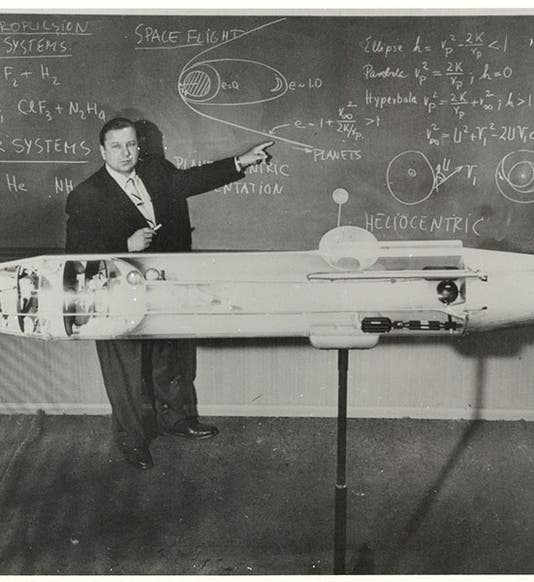

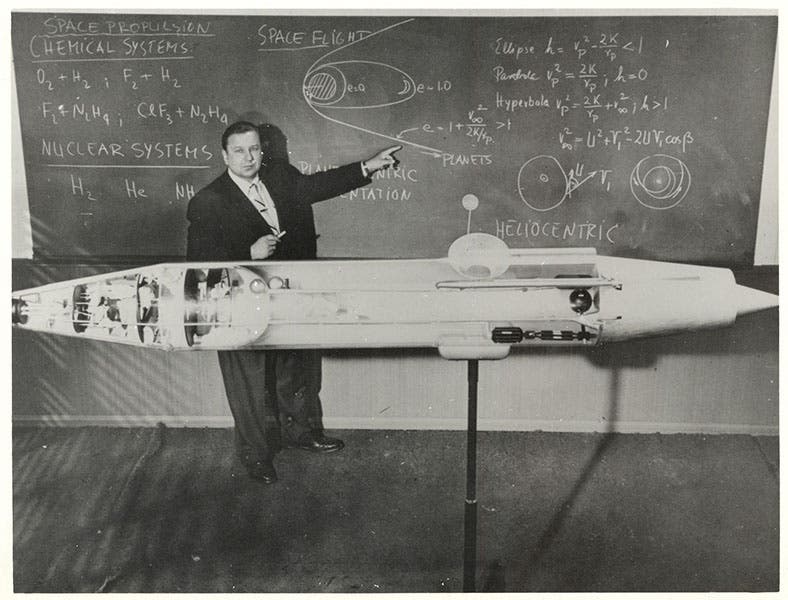

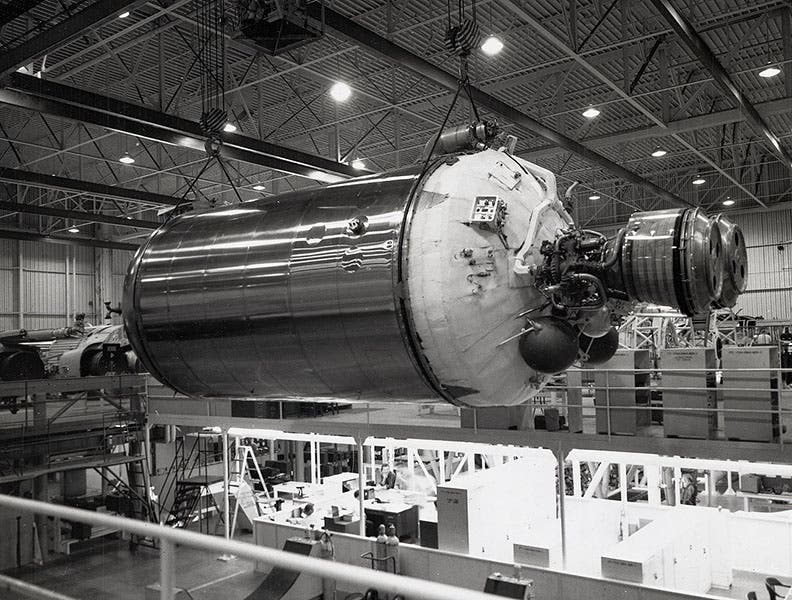

Ehricke worked for a while for von Braun at Huntsville, Alabama, but the two had never really shared the same vision: Ehricke was a dreamer and wanted to be part of the colonization of space; von Braun just wanted his rockets to work, and took the most conservative approach possible. Ehricke went to work for Bell Aircraft, and then transferred to the Convair Division of General Dynamics in the 1950s, which humored his radical ideas. Ehricke helped Convair develop the Atlas rocket, which was to be the mainstay of both ICBMs and the first planetary probes of the 1960s. The original second stage on the Atlas rocket was the Agena, which used a liquid hydrazine-derivative fuel and was perfectly suitable for many uses. Ehricke invented a new kind of second stage, called the Centaur, which used liquid hydrogen as the fuel and liquid oxygen as the oxidizer (second image). This was quite a challenge to design, because to keep the hydrogen liquid, the tanks must maintain a temperature of just a few degrees above absolute zero. Moreover, to save weight, the fuel tanks were ultra-thin and maintained their shape only under high pressure. The reward however was great: more powerful thrust for the second stage, which meant larger payloads. Ehricke's Centaur was first used for the Lunar Surveyor missions in the mid 1960s, and then for the famous Viking missions to Mars in 1976 and the Voyager missions to the outer planets in 1977. Centaurs have flown hundreds of space missions and are still in use.

By the time his Centaur was launching spacecraft to Jupiter and Saturn, Ehricke had turned his interest to the colonization of the Moon and of space. He believed that humankind was doomed to shortages and repression if humans remained confined to Earth; we would inevitably run out of resources. He preached what he called the Extraterrestrial Imperative – the absolute necessity of developing off-Earth colonies. He designed, or at least conceptualized, a variety of space shuttles, orbital habitations, and lunar settlements. We see below (fifth image) an artist's rendering of his proposed Selenopolis, a lunar city. None of his futuristic spacecraft were ever built. but quite a variety of them went into production as space model kits, offered by the likes of Revell and Fantastic Plastic. They are quite popular among collectors (fourth image).

Shortly before his death, Ehricke received the Goddard Astronautics Award, named after Robert Goddard and bestowed annually by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) for lifetime achievement in the field. Only three Operation Paperclip subjects ever received this honor: von Braun, Ehricke, and Hans von Ohain. When Ehricke died in 1984, he requested that his ashes be sent into space, whenever that became possible. On Apr. 21, 1997, a Pegasus XL rocket carried his ashes and that of 23 others into deep space, on the Founders Flight, as it is called, the first such deep-space burial mission. Sharing the urn with Ehricke were the ashes of Gene Roddenberry, creator of Star Trek, and LSD devotee Timothy Leary. That must have been quite a ride.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.