Scientist of the Day - Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci, everyone’s quintessential example of a Renaissance man, died May 2, 1519, at age 67, in Amboise, France, After training in Florence, Leonardo spent much of his working life in Milan, working for Ludovico Sforza, before moving to France in 1516 at the request of King Francis I. We wrote a post on Leonardo on his birthday last year, in which we discussed his inventions, almost all on paper, and his inventiveness in general. Today, we are going to look at his unprecedented anatomical studies, of which we have a splendid visual record.

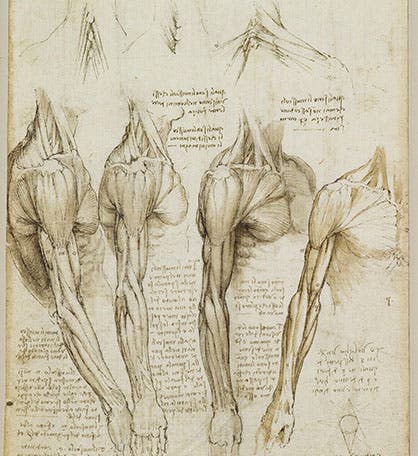

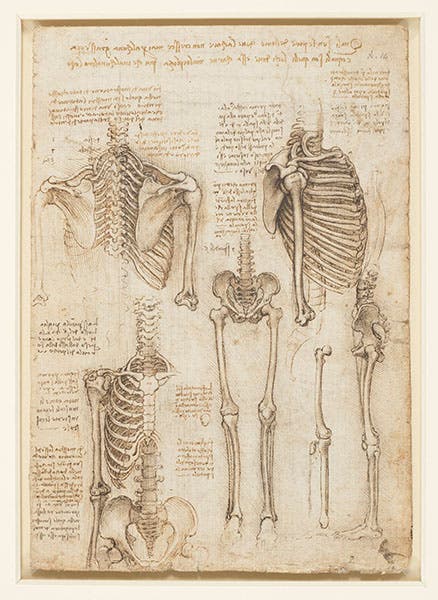

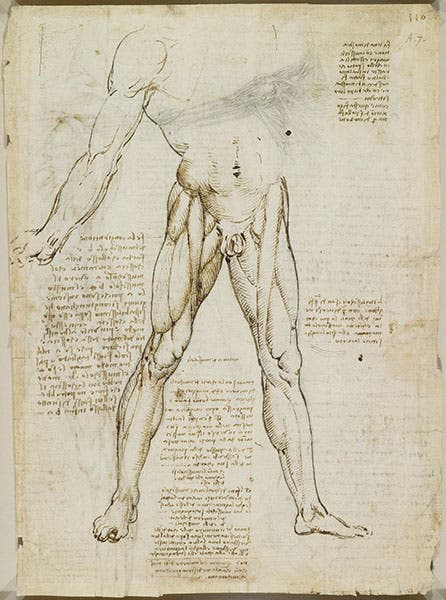

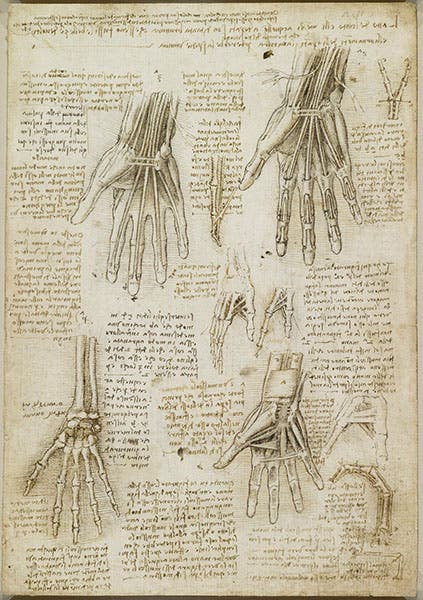

Leonardo began doing dissections in the 1480s, in order to improve his depictions of the musculature of the human body. Over the next 30 years, he dissected some 30 cadavers, which was 30 more than most physicians and professors of anatomy of his time had done. He intended to publish an anatomy textbook, but like most of his projects, it came to naught, except that Leonardo did gradually accumulate a detailed portfolio of anatomical drawings. After his death, all of Leonardo's drawings, including the anatomical ones, went to one of his protégées, Francesco Melzi, and after Melzi’s death, they were bought by Pompeo Leoni, the court sculptor to the King of Spain, who had them sorted and bound in large folios, some of which ended up in Madrid.

After Leoni's death in 1609, one of the Madrid volumes was acquired by an English collector, Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, and it happened to be the volume containing nearly all the anatomical studies. By 1690, at the latest, the volume had found its way into the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. There it sat for another near-century, unnoticed and unloved, until the drawings were recognized as Leonardo's by the Scottish anatomist, William Hunter, in 1773. Over 250 years had elapsed since Leonardo's death. Fortunately, the drawings never again went into hiding, and they are now one of the treasures of Windsor Library. All of the drawings in this folio, all 810 of them (of which perhaps 150 are anatomical), are available online. We have drawn on them for this post.

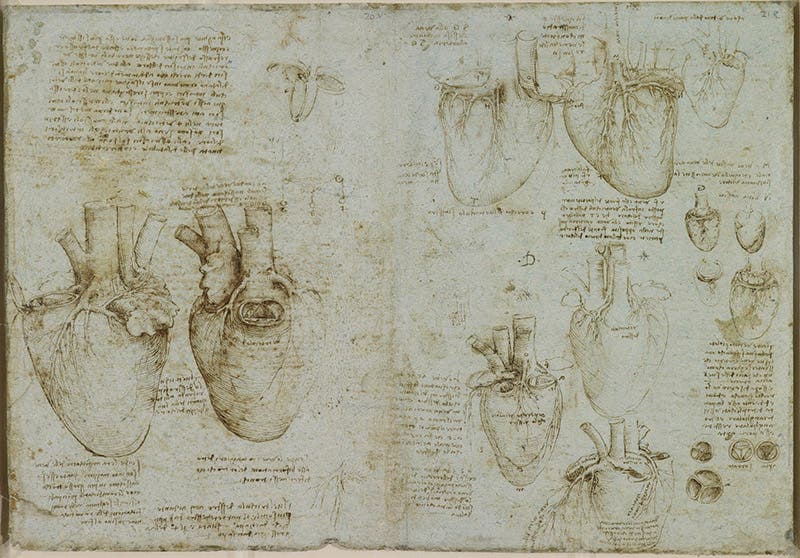

To appreciate Leonardo’s anatomical drawings, one must realize that never before had anyone combined a scientific interest in the human body with the artistic ability to record knowledge gained with images rather than words. Illustrations in anatomy texts, whether manuscript or printed, were not informational at all, but decorative, and seldom reflected any first-hand acquaintance with the human body. Leonardo’s drawings were completely different, full of information, and drawn with consummate skill.

All of the notebook pages we show here date from the period 1508-13, and it is apparent that by this time Leonardo was no longer studying anatomy for the sake of his painting, but was pursuing anatomy for its own sake, because it revealed the infinite complexity of Nature’s plan. There is practically nothing in these drawings that would make one a more accurate painter of the human body. He studied the heart (in this case an ox or cow heart) because it fascinated him as an organic engine, as he wondered why a tricuspid valve was superior to one with two or four flaps (sixth image, below).

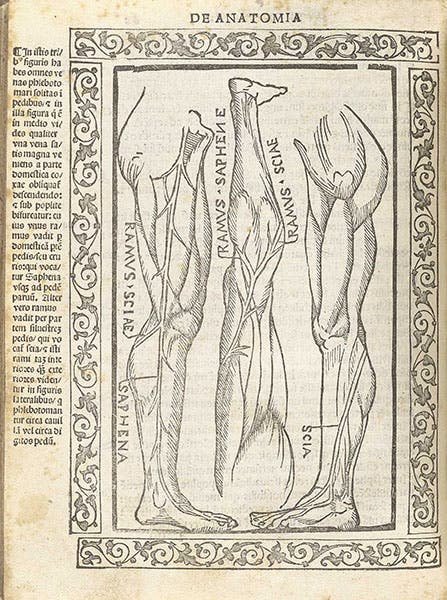

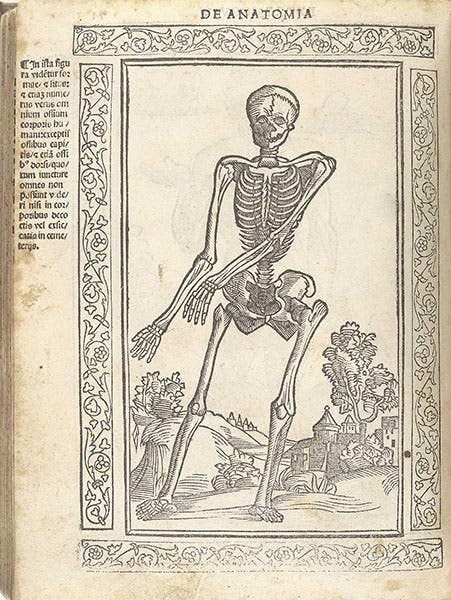

The tragedy of Leonardo’s anatomical studies is that they had no impact on anatomical illustration at all. Leonardo had discovered that the best way to record anatomical facts is through illustrations made firsthand by a competent artist. Andreas Vesalius had to discover this all over again in1543, and his artist was nowhere near as competent as Leonardo. But it was Vesalius who inaugurated a revolution in anatomy, not Leonardo.

The best was to appreciate the opportunity missed is to look at one of the many books on anatomy published in the first forty years of the 16th century. We chose one of the best, by Jacopo Berengario da Carpi, his Isagoge Breves, which contains 23 woodcuts of the human body, some of them rather stylish complete bodies, others showing individual organs or limbs, just like Leonardo. We show two of them here (seventh image, above, and eighth image, below), from the copy in the National Library of Medicine. What a difference! Carpi’s book was published ten yeas after Leonardo had dissected his last cadaver, and it is apparent that his years of study and his beautiful drawings had made no difference at all, because no one knew about them.

Since we have been talking about drawings in the Windsor Library codex, it seems appropriate to mention that there are hundreds of other drawings in the codex, not related to anatomy at all, but charming and well worth knowing about. I chose two to include here. One is a drawing Leonardo did around 1493, showing a man beset by a band of gypsies (ninth image, below). It is a “grotesque,” as such drawings are called, with the faces in caricature, and unlike his anatomical drawings, it seems to have been known to others, perhaps to Hieronymus Bosch, whose Christ Carrying the Cross in Ghent (1515-16) has a similar set of grotesque faces.

At the opposite extreme is a lovely study of the coiffure of Leda, done for a painting of Leda and the Swan that is now lost (tenth image, below). It is such an attractive and appealing drawing that Martin Kemp used it for the dust jacket of his book, Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvelous Works of Nature and Man (1981), still one of the best introductions to Leonardo as scientist and artist.

In our first post on Leonardo, we showed the red-chalk portrait of Leonardo done by Melzi around 1509, also in the Royal Library at Windsor. For this occasion, we use the more famous self-portrait, also executed in red chalk, dating to about 1512, and in the Biblioteca Reale in Turin (second image)

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.