Scientist of the Day - Leonid Kulik

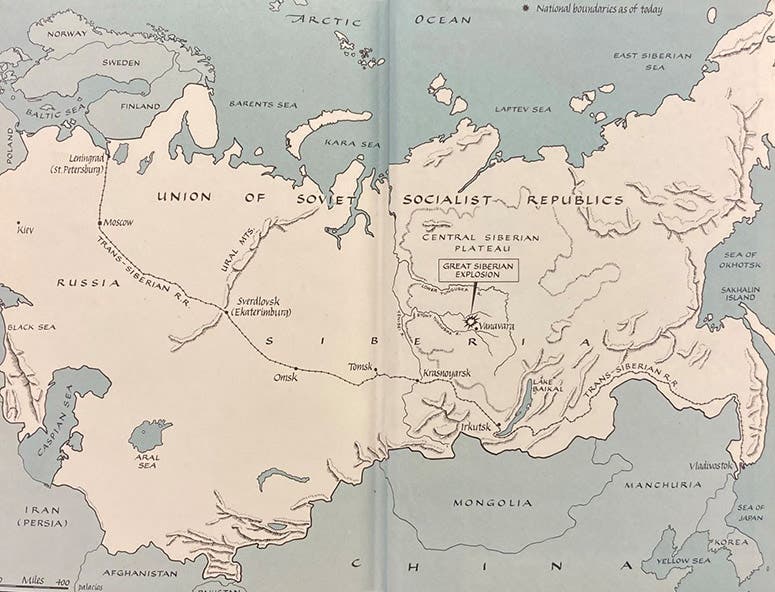

On June 30, 1908, something exploded about 5 miles above the boreal forest (taiga) in central Siberia, in an uninhabited region north of the Stony Tunguska River (see map, third image). The "event," as it is still called, produced a brilliant fireball, radiated an intense amount of heat that was felt many miles away, and flattened about 800 square miles of trees. Fifty miles from ground zero, Native Tungus, or Evenks, as they are now called, were thrown from their horses, boats, or beds. Reindeer herds panicked and fled. It was the largest natural explosion of the 20th century. Had it occurred anywhere else, say on the eastern seaboard of the United States, it would have been the event of the century, bar none.

But central Siberia is practically uninhabited. No villages or towns were directly affected; only a few deaths were reported. Millions of animals must have died, but no one was aware of it. Local newspapers carried stories about the flash, and the noise, and the heat, but those in more civilized areas who read those stories dismissed them as the products of local superstition. No one went to investigate.

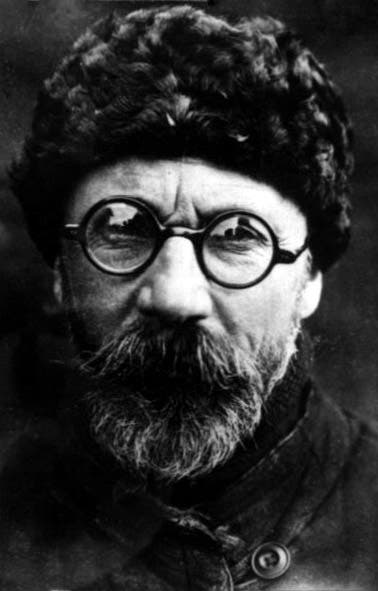

Enter Leonard Kulik. Kulik was an Estonian, born Aug. 19, 1883, who studied forestry but became a mineralogist, teaching in Tomsk (which is on the Trans-Siberian Railway, not terribly far from the Tunguska Rivers), before settling in St. Petersburg, where he was placed in charge of the meteorite collection at the Mineralogical Museum run by the Academy of Sciences. Kulik heard the rumors about what sounded to him like a meteorite impact, perhaps while he was in Tomsk, and after the war (in which he served in the Russian military), he convinced the Academy of Sciences to sponsor a trip to the region. This was in 1921. Bear in mind that no one knew the location of the impact site, if there was an impact, within 500 miles, because, in the thirteen years since the event, no one had been sent to inquire further. On this first trip (for which the Trans-Siberian Railway gave him a car for his personal use), Kulik did not see any evidence of a cosmic disaster, but he interviewed scores of people who recalled the bewildering flashes and rumbles and blown-down tents of June 30, 1908, and he became convinced that there was a meteorite impact site out there to the north, waiting to be discovered, with perhaps tons of meteoritic iron that would be worth a lot of money.

Map of Russia, showing the location of the Tunguska event (Great Siberian Explosion), north of the Stony Tunguska River; the Trans-Siberian railroad runs across the lower part of the map; endpapers of The Fire Came By: The Riddle of the Great Siberian Explosion, John Baxter and Thomas Atkins, Doubleday, 1976 (Linda Hall Library)

Most of his colleagues at the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg (then called Petrograd) dismissed the stories Kulik told them, and it took him 6 years to persuade his superiors that it was worth further investigation. In 1927, he returned with a small party to see if they could locate an impact site. The window for exploration was small, just the months of March and April. Any earlier, it was too cold and there was too much snow; any later, and the marshy floor of the taiga would have started to melt, the insects would be swarming, and passage would be impossible. There were no roads or even trails to follow.

Kulik left St. Petersburg in early 1927 (the name had changed again to Leningrad) by the Railway, left the train at Kansk, made it north to the Stony Tunguska River and the town of Vanavara, where he found a guide and collected more tales that directed him further north. Horse-drawn sleighs had got them this far, and now it was foot traffic only, with reindeer as pack animals. But ultimately, they were rewarded with an amazing sight – forests of trees completely leveled, with the tops of the trees all pointing south, and showing evidence of scorching (first image). As they explored the area, they found that the fallen trees formed a vast radial ring, with the tops of the felled trees pointed outward, away from a center, presumably the point of impact. But when Kulik got to the center, he did not find the expected crater, like the one in New Mexico examined by Daniel Barringer a few decades earlier. Instead, he encountered what he called a “telegraph-pole forest,” with dead trees still standing, but stripped on all their branches (fourth image).

View of “telegraph-pole forest,” at the center of the region affected by the Tunguska event, photograph taken on the Leonid Kulik expedition, 1927, reproduced in The Fire Came By: The Riddle of the Great Siberian Explosion, John Baxter and Thomas Atkins, Doubleday, 1976 (Linda Hall Library)

Kulik was hampered in his investigations (he would return 3 times to the Tunguska area) by his conviction that the cause of the event was a meteorite impact, and that there must be meteorite fragments in the ground. It is now realized that the meteorite (usually called a bolide) did not strike the ground, but exploded some miles above the surface, and left no fragments at all. The trees left standing were directly below the explosion, where the destructive force was straight down.

Nevertheless, Kulik was the hero of the Tunguska event, the man who persevered when all his friends told him he was chasing a wild goose, and he was hailed in the 1930s as Russia’s preeminent mineralogist and meteorite man. He died during the war, in 1942, at the age of 58. When the Soviet Union issued a postage stamp to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Tunguska event, Kulik’s portrait was on the stamp (fifth image).

I am sure we have some of Kulik’s original journal publications in the Library – our Russian language collection is excellent – but I, hampered by an inability to read Russian, could not track them down, and even if I had found them, I would have been unable to read them. Perhaps we can revisit Kulik in a few years and I can get some help identifying some of the primary sources we might have concerning the Tunguska event. That would be interesting.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.