Scientist of the Day - Leopoldo de’ Medici

Leopoldo de' Medici, an Italian nobleman and patron of the sciences, was born Nov. 6, 1617 (see first image above). Leopoldo was the younger brother of Ferdinando II de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, who ruled Florence for nearly fifty years (third image). Ferdinando had a great interest in experimental science--he was the patron of Galileo, and stood up for him, as well as one could, when the Pope came calling with the Inquisition in tow--but he had little time to satisfy his scientific curiosity. Leopoldo, with nothing really to do at court, had plenty of time, and lots of ideas. Galileo's disciples, such as Evangelista Torricelli, were inventing barometers and playing with pendulum clocks in the 1640s, and Leopoldo encouraged those inquirers to pursue their experiments at the Pitti Palace, where the Medici family lived. This patronage was formalized in 1657, when the Accademia del Cimento (Academy of the Test or Trial) was founded.

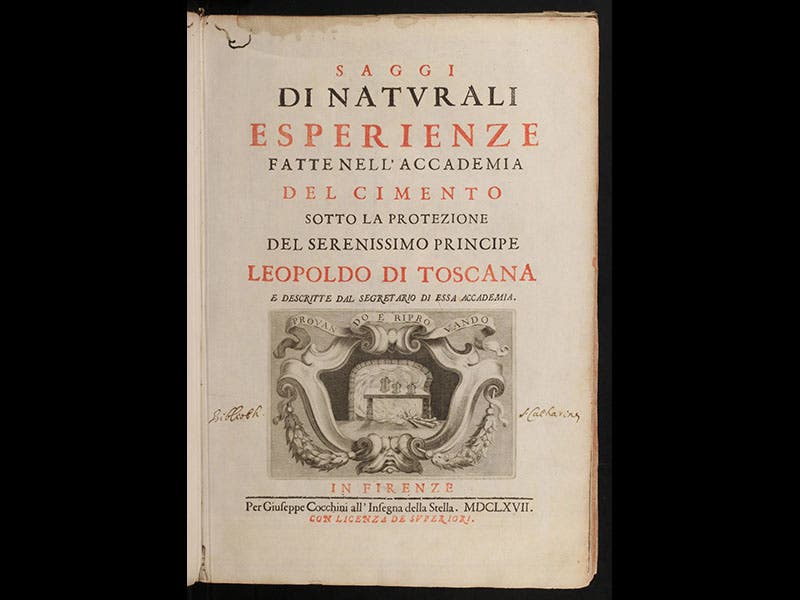

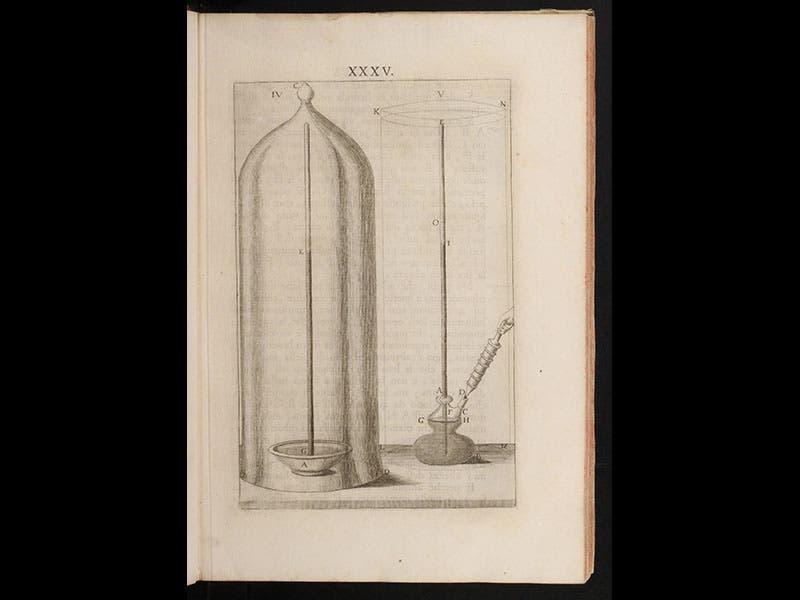

The Cimento Academy had a motto “(provando e riprovando”, “test and test again”) and a crest (second image) and a secretary to record the results of their experiments. It is often called one of the first scientific societies, and in some ways it was, but one must always remember that the members were selected by Leopoldo, and the experiments and demonstrations were chosen to meet Leopoldo's desires, so in many ways it was more of a patron's circle than an independent scientific organization. But Leopoldo chose his members well, and the Cimento group included such distinguished investigators as Giovanni Alfonso Borelli and Francesco Redi and, for a short time, the geologist Nicolas Steno. Not surprisingly, when Leopoldo lost interest after ten years, and sought (successfully) to become a Cardinal in the Church, the Academy folded up its tent. Fortunately, Leopoldo encouraged the secretary, Lorenzo Magalotti, to publish an account of the experiments that were performed over the course of ten years, and the Saggi di naturali esperienze appeared in 1667 (second, fourth, fifth images). It was a considerable ornament to Leopoldo and the Tuscan court, and a milestone in the history of experimental science. We have four editions of the Saggi, including the first, in our History of Science Collection.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.