Scientist of the Day - Leoš Janáček

Leoš Janáček, a Czech composer, died Aug. 12, 1928, at the age of 74. He shines as one of the Summer Triangle of great Czech composers, along with Antonín Dvořák and Bedřich Smetana. So far as we know, Leoš Janáček had no interest in science and made no contribution to natural philosophy. But we are going to celebrate his birthday today anyway, for reasons that may become apparent, or may not. A charming portrait photo shows Leoš and his wife Zdenka, when Leoš was age 27 (first image).

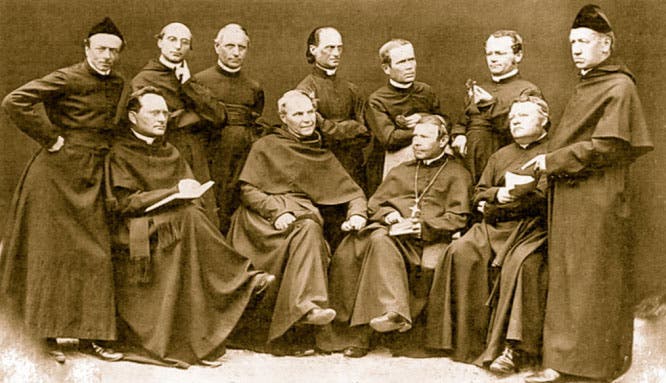

On Feb. 8 and Mar. 8 of 1865, Gregor Mendel of the Augustinian Abbey of St. Thomas in Brno, Moravia (now the Czech Republic), gave two papers to the Natural History Society of Brno, in which he announced the results of ten years of experiments on crosses with pea-plants. The findings, which revealed that traits lost in one generation can return in the next in a mathematically predictable way, were unexpected, and also unappreciated. Mendel is the second from the right in the photograph from 1862, holding a pea plant (second image).

Several months later, Leoš Janáček, all of 11 years old, enrolled as a choral scholar at the Augustinian abbey in Brno (third image). The Abbey had a long tradition of offering scholarships to young boys to be educated and to sing in the Abbey choir – in fact, they had an endowment for just such a purpose. Janáček was one of a small number of choristers; they wore light blue suits when they processed and were known locally as the "Bluebirds." Janáček would be a bluebird for four years. He was there in 1866 when Mendel's papers were published, to no notice whatsoever (not until 1900 would the significance of Mendel’s work be recognized). Janáček was there in 1867, when the incumbent abbot died, and Mendel was chosen to succeed him. And he was there for two more years, with Mendel, as abbot, reviewing Janáček's report card every 6 months and counseling the lad on the progress, or lack of it, in his studies. What was said between the two on these occasions was not recorded by either party, then or later.

Brno at the time had a sizable population of German-speaking citizens, who called their city Brünn, and many of the cultural venues, such as the opera, gave performances in German, not Czech. Janáček was an ardent nationalist, proud of his Moravian heritage and Czech tongue. He revered Dvořák and had doubts about Wagner. He went to Prague to further his musical education, then returned to Brno to establish an organ school, to teach, and to encourage the founding of a Czech opera company. He also was the music director and organist at the Abbey of St. Thomas, so again, he and Mendel must have had regular encounters. Mendel spoke and wrote in German, and whether he and Janáček had any disagreement over the appropriate choral language for the choir, is not known. It is known, however, that when Mendel died in 1884, Janáček played the organ at his funeral services.

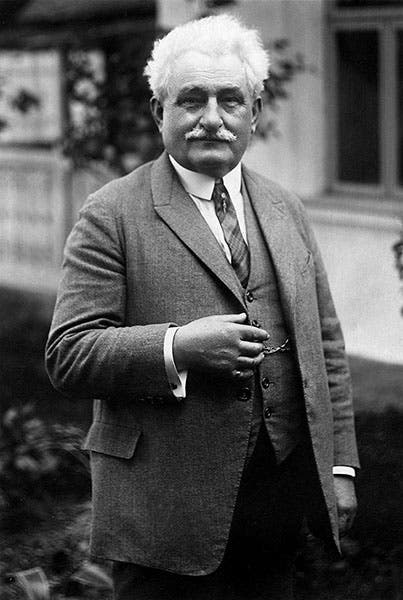

Janáček lived until 1928 and always called Brno his home. We include a photo of an older Janáček, looking cherubic, which he certainly was not (fourth image). His music, like that of Dvořák, was rich in folk melodies, rhythms. and tunings, and was thoroughly Czech. I know little about Janáček's music except that I like what I have heard, which is his Sinfonietta, his Taras Bulba rhapsody, the Glagolitic Mass, with the singing parts in Old Slavic, and some of his piano sonatas, miniatures, and sketches (the links here are to YouTube performances, sometimes extracts, so you can at least get a feel for Janáček's music). Two years ago, I was introduced to a lovely composition for piano and cello called Pohádka (Folk Tale), recommended to me by Erika Honisch, a musicologist at SUNY Stony Brook, and my go-to person on Bohemian and Czech music and culture.

But one piece that Janáček wrote seems especially fitting for our stretch-of-a-theme today. It is called Pochod Modracku – March of the Bluebirds – and recalls his four years as a chorister at the Abbey of St. Thomas during Mendel's time. It survives in two versions, the first as a stand-alone piece, orchestrated for piccolo and keyboard, and then as the third movement of a larger work called Mladi (Youth), which is a woodwind sextet. The second is more pleasing as a video, since you get to look at the performers instead of an album cover. If you choose the wind sextet, the March of the Bluebirds begins at about the 10-minute mark. Both versions were written in 1924, almost 60 years after Janáček entered Mendel's abbey. What the musical record tells us about his chorister years is difficult to extract, but at least it is there to be interpreted. The textual record is virtually silent.

Janáček did not acquire much prominence as a composer until the 1920s; before then, his compositions were practically unknown, even in Moravia. It is interesting to realize that had Janáček died at the age Mendel was when he passed away (61), he would have been as little known in his field as Mendel was in genetics. And he might not have been rediscovered, since many of his most-played works were the product of his last fifteen years of life. Sometimes it pays to outlive your detractors.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.