Scientist of the Day - Liu Cixin

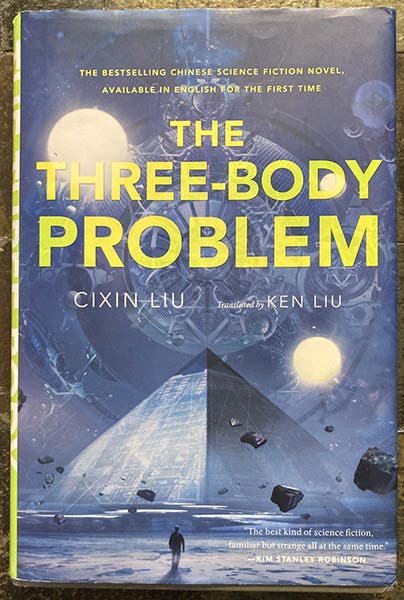

Dust jacket, The Three-Body Problem, by Liu Cixin, trans. by Ken Liu, Tor Books, 2014 (author’s copy)

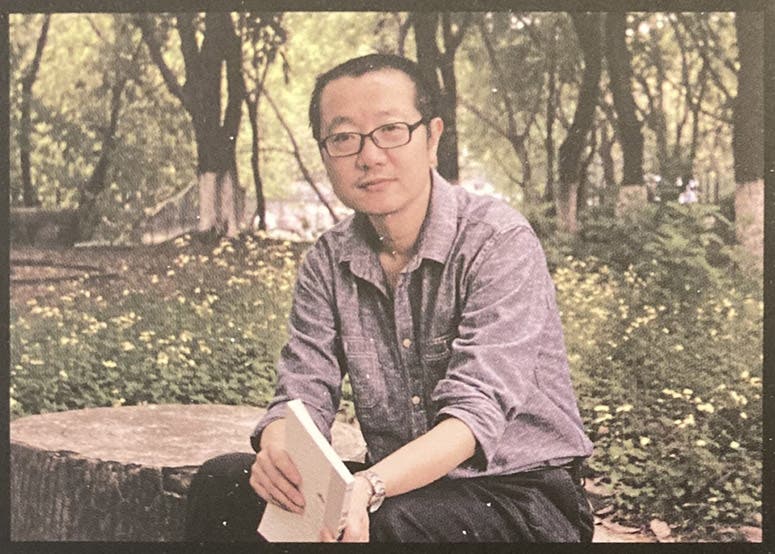

Liu Cixin, a Chinese science fiction author, was born June 23, 1963, in Beijing. He grew up in Shanxi province in northern China during the Cultural Revolution, then moved to Henan province in central China, where he graduated from college with a degree in computer engineering. He worked as an engineer in Shanxi for some years.

Portrait of Liu Cixin, photograph from dust jacket flap, Death’s End, by Liu Cixin, Tor Books, 2016 (author’s copy)

Liu started writing science fiction in his early twenties, inspired by western authors like Arthur C. Clarke. He wrote short stories at first; by 1999, he had won the first of many Chinese Galaxy awards, which are the equivalent of the Hugo award in the West. Liu then turned to writing sci-fi novels, publishing one in 2004 and a second in 2005, both in Chinese. In 2006, his third novel was published, again in Chinese, and this one put Liu on the world map, both in sales and in critical acclaim. The novel was called (in translation) The Three-Body Problem. It told the story of an alien civilization, the Trisolarians, who lived on a planet that chaotically orbited three suns, so that the entire civilization was regularly destroyed by changes in orbit that could not be predicted (that’s the 3-body problem). When they receive a message sent out by a disgruntled human victim of the cultural revolution, they immediately send out a fleet of starships to destroy humanity and take over our better-behaved solar system.

Since they realize that during the 400 years it will take the invasion fleet to arrive from Alpha Centauri, we might acquire the technical know-how to destroy the fleet, the Trisolarians send two multi-dimensional computers, folded up to the size of protons, to disrupt our technology and ruin every experiment, so that Earth science comes to a standstill, as we try to figure out what to do next.

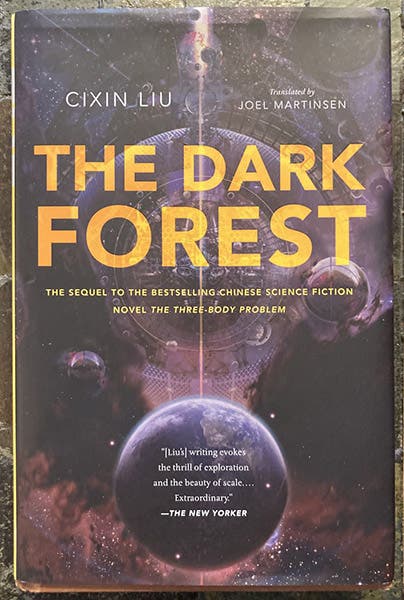

Dust jacket, The Dark Forest, by Liu Cixin, trans. by Joel Martinsen, Tor Books, 2015 (author’s copy)

The book was translated into English and published in the West in 2015 as The Three-Body Problem. I, like tens of thousands of eagerly expectant readers, obtained a copy before the ink was dry and was soon absorbed in what turned out to be the saga to end all sagas. This surprised me, because I generally do not like sagas or epics or multi- generational tales of any kind; many modern sci-fi novels are multi-volume chronicles, and I have never been interested, for whatever reason.

But The Three-Body Problem was different, probably because it addressed directly one of the great conundrums of our era: The Fermi Paradox. If the universe is filled with alien civilizations, as probability studies suggest that it must be, then where are they? Many solutions have been offered, but Liu's, while not original, is forcefully and ominously presented, especially in the follow-up volume, the title of which – The Dark Forest (2015) – is now the label given to one solution to the Fermi Paradox, which I urge you not to look up, if you have not read the series and intend to.

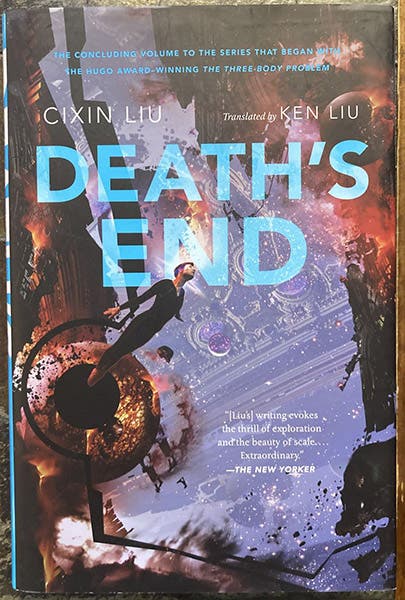

Dust jacket, Death’s End, by Liu Cixin, trans. by Ken Liu, Tor Books, 2016 (author’s copy)

The third and last volume, in what is now the greatest sci-fi publication of the 21st century, was published in English in 2016 as Death’s End, and it was just as suspenseful and thoughtful as the preceding two. I was quite blown away. Like many others, I waited for Hollywood to come calling. They never did, but Netflix barged in and took it on, and an 8-part series based on the first volume was released in the spring of 2024. I watched it as it was released, and then several times more, and while it was enjoyable enough, it could hardly, in its allotted time, capture the nuances and side-trails of a full-length novel, especially when the producers had the nerve to move most of the action – and the characters – from China to England. We shall have to see how they do with The Dark Forest, especially since they have already borrowed one of the second book's most ingenious ideas – the "Wallfacer Project" – for the first series.

I have noticed that recent articles, such as those on Wikipedia, insist that the trilogy has a name – Remembrance of Earth's Past, a la Proust. I looked carefully at all three volumes that I own, all first editions, and that rubric appears nowhere in any of them, or on the dust jackets. I am curious as to whether Liu came up with it himself, 20 years later, or whether some spin jockey at Macmillan has recently foisted it upon us. Until I find out, I will not be using the new rubric.

Incidentally, the English-language publications give the author as Cixin Liu, moving the surname Liu from first (the Chinese way) to second (the English manner). You can also find in bookstores, translations of Liu’s Wandering Earth (2017), a collection of stories, and two other novels, Ball Lightning (2018) and The Supernova Era (2019). These, except for several short stories, were written before The Three-Body Problem and have been newly translated to meet demand for books by Liu.

If you have not read The Three-Body Problem, I hope you will give it a try, even if you are not a fan of science fiction. There is a lot to be said for a book that not only tells a great story, but gets you thinking about cosmic questions, such as how humanity might and should react to the discovery of intelligent life elsewhere in the cosmos.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.