Scientist of the Day - Loren Eiseley

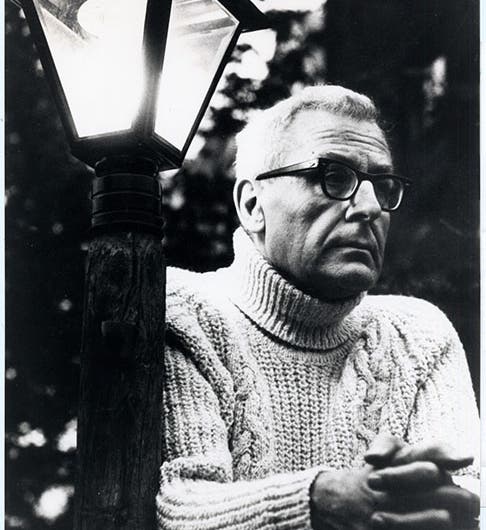

Loren Eiseley, an American nature writer and anthropologist, was born Sep. 3, 1907, in Lincoln, Nebraska. He ultimately became the Benjamin Franklin Professor of Anthropology and the History of Science at the University of Pennsylvania, which is about as distinguished a title as you could have, at as fine a University as you can find, and yet, if he had any significant accomplishments in either field, I do not know what they were. Eiseley was not known for being a teacher or an academic. His fame and reputation come from his essays about nature, the history of life on Earth, and man's place in the natural order.

Eiseley’s early life was hard. His father was a salesman who never earned much. His mother, for whom he had little affection, was deaf and mentally ill. One salvation of his childhood was the Lincoln Public Library, where books provided an introduction to the world beyond. The world at hand he explored for himself, since they lived at the edge of town and had woods, swamps, and meadows to explore. The pattern of his life was pretty much established there, except for the writing, which came later.

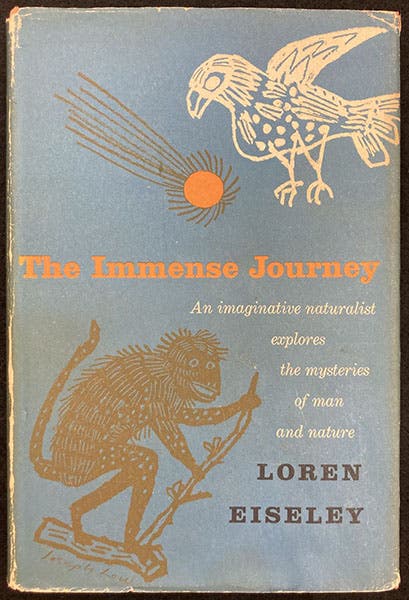

Dust jacket, The Immense Journey, by Loren Eiseley, 1957 (author’s copy)

Eiseley dropped out of school and hopped freights to go west, an activity he would resume during the Great Depression. Somehow, he managed to get into the University of Nebraska, and later he earned his PhD at the University of Pennsylvania, to which he would return after stints teaching at the University of Kansas and Oberlin. He would be in Philadelphia for the rest of his career.

Eiseley burst on the literary scene in 1957 with his first book of essays, The Immense Journey. I first encountered these thought pieces in Okinawa in the late 1960s while patrolling the flight line in my junior officer maintenance truck and waiting for the B-52s to come home. My initial reaction was the same as my reaction now, when I return to read an essay: Wow, that man can write! Eiseley is not especially quotable, but his prose is deep and dark, and powerful almost beyond measure. People ask me, what does he write about, and I can't tell them: I say, vaguely, he writes about time, and the evolutionary past, and human aspirations and misapprehensions. He is often called the modern Thoreau, and that is accurate enough, although he is far more pessimistic, in a gentle way, than Thoreau ever was. Two other books of essays that I have read are The Firmament of Time (1960) and The Unexpected Universe (1969). Both are just as thoughtful and as beautifully written as the first. There are two more volumes from the 1970s that are also highly regarded but which I have not read.

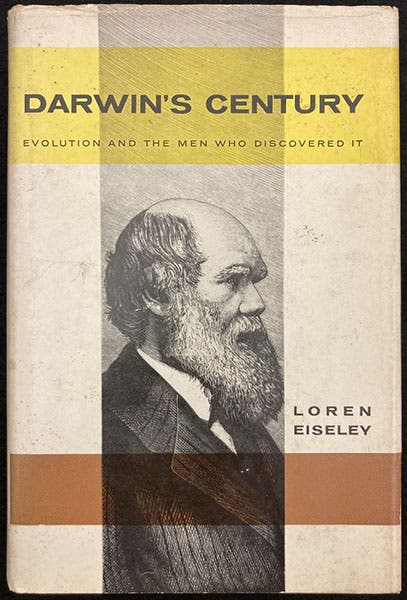

Dust jacket, Darwin's Century: Evolution and the Men Who Discovered It, by Loren Eiseley, 1958 (author’s copy)

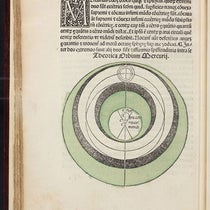

In 1958, Eiseley published his second book, and it is quite different from any of his other works. It was titled: Darwin's Century: Evolution and the Men Who Discovered It. Eiseley was not a trained historian of science, but he taught himself to be one, by reading the original sources, instead of secondary ones, which not a bad way to enter the field. Darwin's Century was Eiseley's attempt to sketch out the background that made Darwin possible. He introduced a useful term, the " minor evolutionists," for those who muddled with the struggle for existence, geological time, and natural selection before Darwin welded everything together into a coherent whole in 1859. As one might expect, Darwin’s Century is very well written, and thoughtful, and I used it many times as a textbook for the evolution section of my Foundations of Physical Science course. Students loved discovering that a textbook could be stylish and a pleasure to read, as well as a source of information.

Late in life, Eiseley went down a few rabbit holes he should have stayed clear of, and his autobiography, All the Strange Hours (1975), was bleaker than I could take, although others have praised it. It resembles Leonard Cohen’s last album, You Want it Darker (2016), but without the advantage of being superb poetry set to music. Eiseley was, not surprisingly, an accomplished poet himself; it is too bad, to my mind, that it did not occur to him to put his last thoughts into verse form.

All of Eiseley's books are well worth reading, 60 years later, and if he is new to you, I encourage you to find a copy of any one and read an essay. If you become hooked, it is not a bad addiction to acquire.

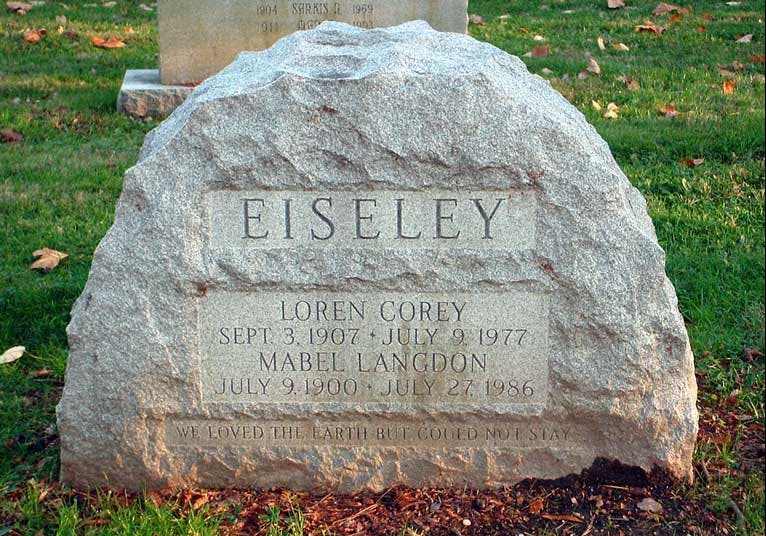

Eiseley died on July 9, 1977, and he and his wife Mabel were laid to rest in West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, Pa, beneath a modest headstone, inscribed with a line from one of Eiseley’s own poems: "We loved the earth but could not stay" (last image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.