Scientist of the Day - Louis Agassiz

Louis Agassiz, a Swiss/American naturalist, was born May 28, 1807, in the canton of Fribourg in Switzerland. Agassiz is best known for discovering evidence of an Ice Age, when much of Europe (and by extension, North America) was covered by glaciers. We wrote a post once on his Etudes sur les glaciers (1840), and exhibited that epochal book in our exhibition, Ice: A Victorian Romance (2008). But before that, when he was still a student in Germany, Agassiz undertook an extensive study of fossil fish, which resulted in the publication of one of the most beautifully illustrated books on fossils ever to appear in print. It consists of 5 quarto volumes of text and 5 suites of hand-colored lithographs of selected fish fossils, from which we selected several to reproduce here, in full and in detail. The book is called Recherches sur les poisons fossiles, and it was issued in parts between 1833 and 1843. Our copy is bound as two text volumes and two atlas volumes.

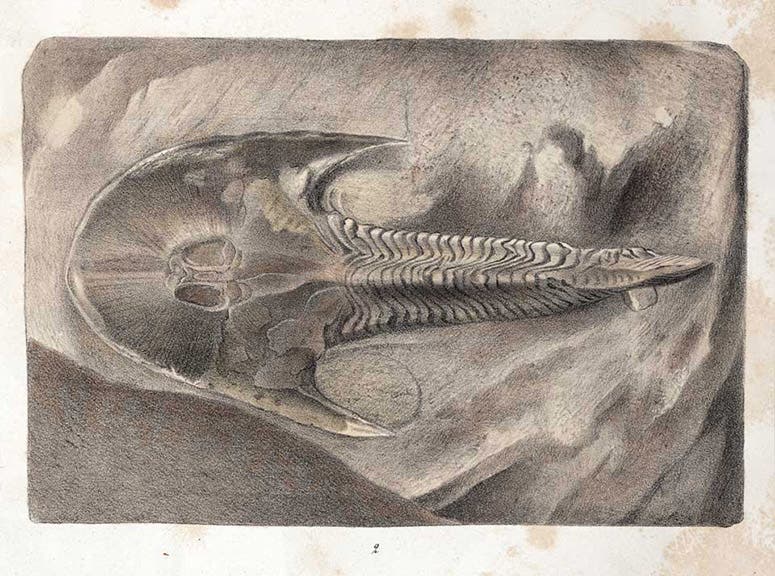

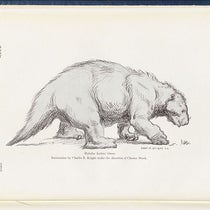

In the text, Agassiz described some 1700 species of fish, and he recognized that most were now extinct. He divided them into four orders, one of those being the placoid fish, with their armored head shields, of which we show a specimen here (fifth image).

I am not professionally qualified to talk about fossil fish, but I can say something about the lithographs. I am regularly astonished at how rapidly lithography became such an expressive medium for scientific illustration. When you realize that the first simple lithographs appeared in scientific books about 1822, it is mind-boggling to see how far the art advanced in just the next ten years, especially in illustrating fossils, for which the lithograph, with its stony texture, is ideally suited.

Agassiz did not do his own lithographs, at least not for this book, but he did have an eye for talent, and Joseph Dinkel, who drew most of the stones for the Recherches, later moved to England and did lithographs for Richard Owen and Gideon Mantell. We shall do a post sometime soon on Dinkel.

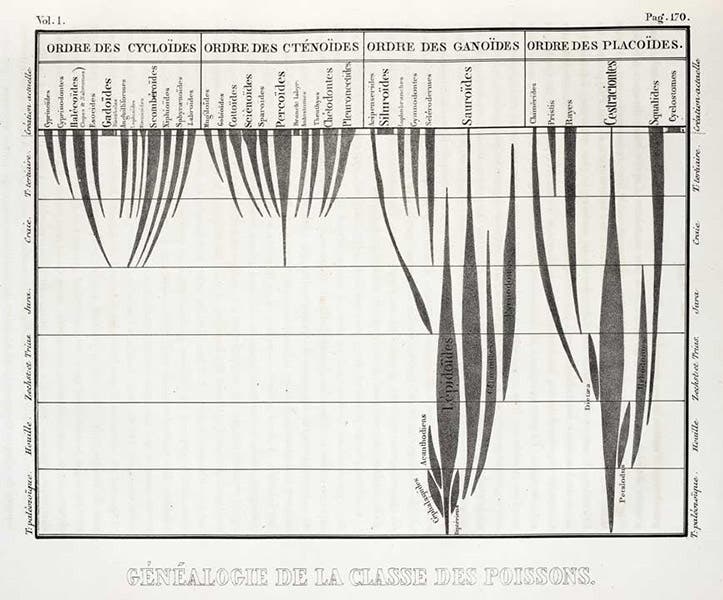

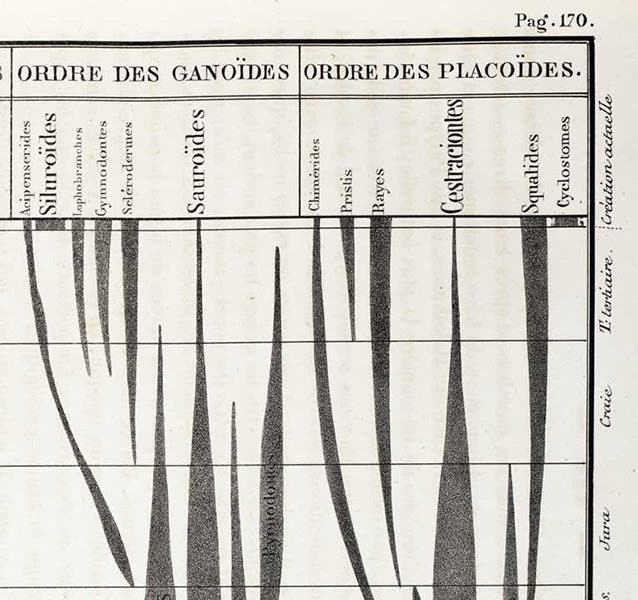

One of the other novelties of Agassiz's Recherches was one of the first uses of a "spindle diagram" as a graphic device, depicting the history of fish on Earth (seventh image). A spindle diagram uses time for a vertical axis, and the horizontal width of the vertical shapes indicates abundance. If they are cut off at the top, that means extinction. Spindle diagrams are often used later to depict evolutionary histories, in which case they connect and morph together. Since Agassiz did not accept evolution in 1833 (or indeed in 1873, the year of his death), the timelines on his spindle diagram for fish do not connect (eighth image).

Someday we will do one more post on Agassiz, to discuss his career at Harvard and his rise to become America's most distinguished and outspoken opponent of Darwinian evolution.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.