Scientist of the Day - Luca Pacioli

Luca Pacioli, a Tuscan mathematician and Franciscan friar, died on June 19, 1517, at about age 70. He was born in Borgo Santo Sepolcro, now known as Sansepolcro, in eastern Tuscany. He was about 30 years younger than another distinguished native of Sansepolcro, Piero della Francesca, whom he must have known, since they both wrote books on perspective and proportion.

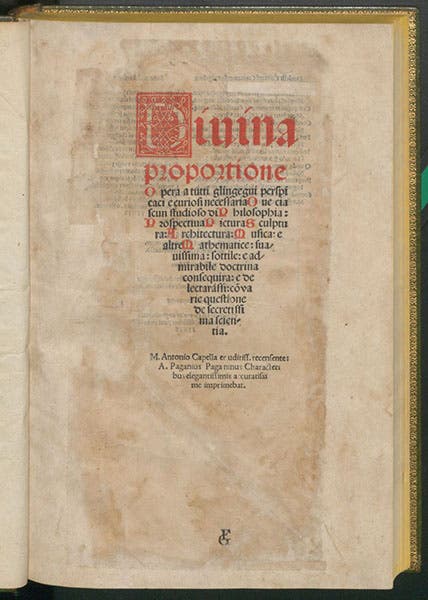

Pacioli taught math at various places, including Venice, for several decades, and in 1494, he published a book, Summa de arithmetica, which is quite well known in the history of accounting, because it introduced double-entry bookkeeping to the West. We have that work in our collections, but we are going to pass it over in order to talk about Pacioli's other book, Divina proportione, which we also have, and which is a much cooler book, at least in my opinion.

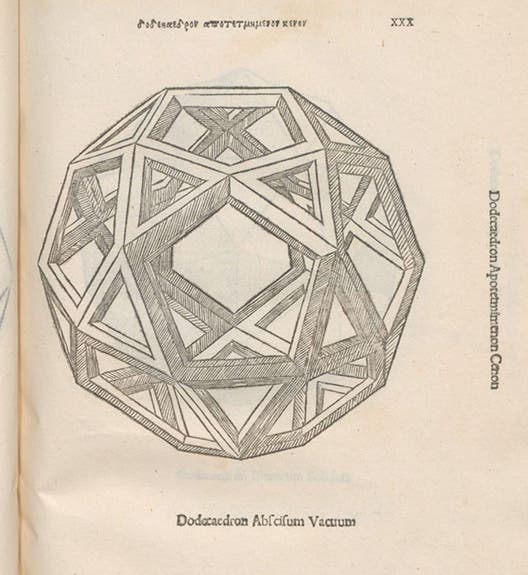

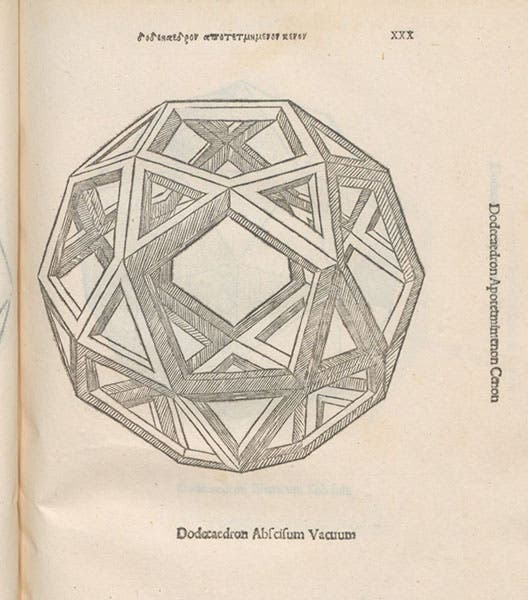

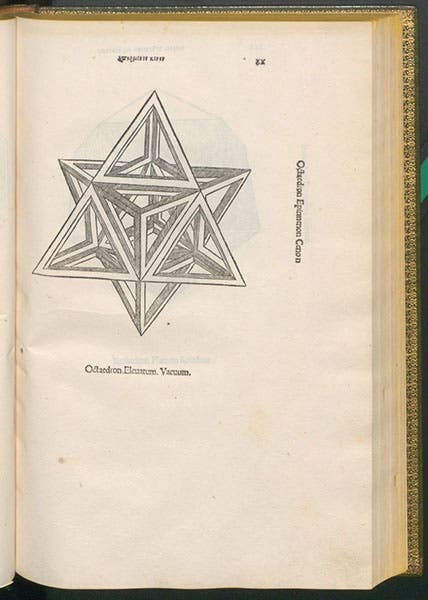

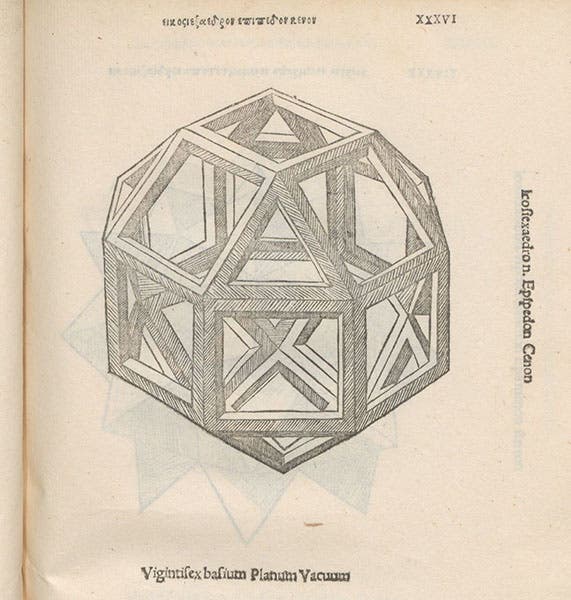

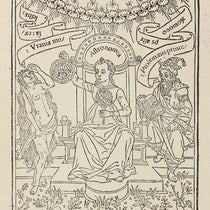

Pacioli moved to Milan in about 1496, and he started writing a book about Euclidean geometry. Euclid’s Elements was mostly concerned with two-dimensional geometry, but in his last book, Euclid discussed geometric solids – polyhedra – especially the 5 perfect or Platonic solids, like the cube and icosahedron, which are about as regular as a solid can get. But one can make others that are almost as special, by lopping off the corners of the perfect solids, leaving semi-perfect shapes exhibiting surfaces of squares and pentagons, or equilateral triangles and squares, and more. Archimedes identified 13 of these, and Pacioli decided to discuss and illustrate these polyhedra in print. He was a pretty good artist himself, and a fine model maker. But he had a new Milanese friend who was much better at drawing, Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo agreed to draw dozens of perfect and truncated solids for Pacioli. The original intent was to produce two illuminated manuscripts for presentation to wealthy and influential patrons, so Leonardo’s original drawings were paintings, and at least some of those survive. But a dozen years later, when Pacioli was long gone from Milan, he decided to turn one of the manuscripts into a printed book. Divina proportione was published in Venice in 1509, illustrated by Leonardo’s drawings, now woodcuts. It is the only book ever illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci.

The Archimedean solids were given their modern names by Johannes Kepler in 1619, which are different from the labels used by Pacioli, but I have used the Keplerian terms in the captions, so that you can look them up if you want. You can learn much more about the topic in an excellent article by Judith V. Field, "Rediscovering the Archimedean polyhedra: Piero della Francesca, Luca Pacioli, Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, Daniele Barbaro, and Johannes Kepler," Archive for History of Exact Sciences, vol. 50, pp. 241-89, 1997.

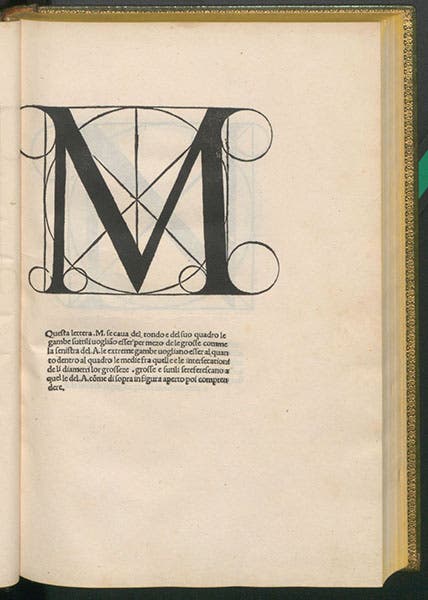

Our copy of Divina proportione looks quite presentable in its later green morocco binding (seventh image), but inside lie the hints of former distress. The title page has been greatly damaged (but without loss of text) and repaired (third image). The entire book has been disbound (if it ever was bound), and reassembled in an odd order, with all of the illustrations coming first, before the text, unlike any other copy I have seen. Fortunately, the pages with Leonardo’s woodcuts are in excellent shape, as you can see. Our copy is a large paper copy, untrimmed, so the solids are off center on the page. I have cropped several of the photos to make them larger and more symmetrical. The book also contains, in is own separate section, all the letters of the Latin alphabet, geometrically generated. We include the letter “M” (fifth image), which I believe the Metropolitan Museum of Art adopted as one of their logos. I also believe Pacioli designed the letters, and not Leonardo.

When our Library was expanded in 1965 with a new annex, six large bronze plaques were commissioned from the noted Florentine foundryman Bruno Bearzi, each with a theme drawn from one of the rare books in our History of Science Collection. These were set into niches in the brickwork of the exterior of the annex. The first one, closest to the front entrance and facing the entry drive, depicts the title page of Pacioli's Divina proportione, with one of Leonardo's polyhedra (the octahedron, our fourth image) added in at the top (eighth image). It is a handsome memorial to our Scientist of the Day. You may read about the other plaques at our post on Bearzi.

Bronze plaque depicting Library’s copy of Divina proportione, by Luca Pacioli, cast by Bruno Bearzi of Florence, installed with 5 others in 1967 on Library annex exterior (recent photo by author)

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.