Scientist of the Day - Luis Alvarez

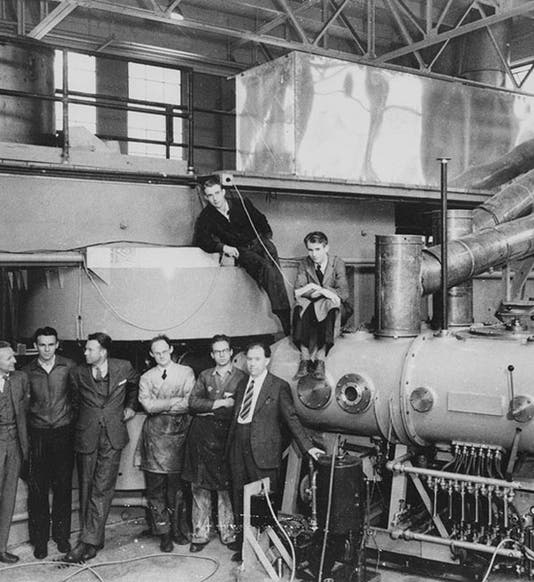

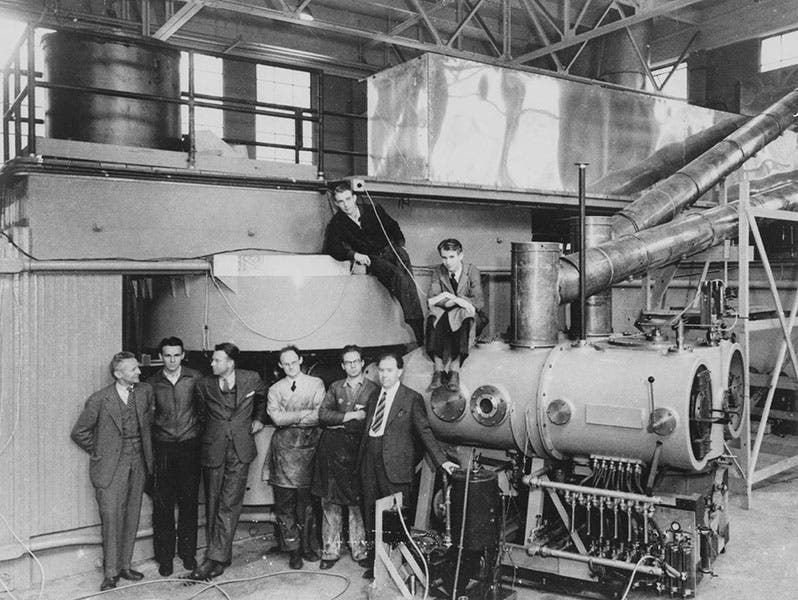

Luis Alvarez, an American physicist, was born June 13, 1911. Three years ago, in our post on Emilio Segré, we mentioned and showed the Time Magazine cover of Jan. 2, 1961, which honored 15 U.S. scientists as a collective Man of the Year (you can see just the cover here), and we mentioned that there were several notable omissions from that cover, including Richard Feynman, Hans Bethe, and James Watson, each of whom would soon be awarded a Nobel Prize. The other serious omission was Alvarez. He was an experimentalist with amazing talent in his fingers, but with a substantial grasp of theory, and that is what set him apart from most of his contemporaries. Before World War II, he worked for E.O. Lawrence at Berkeley, designing magnets for increasingly larger cyclotrons (first image). He played a key role in developing airborne microwave radar in the first years of World War II, which would save Britain, and he also invented Ground Controlled Approach (GCA) radar, which made it possible for air traffic controllers to bring in an airplane even in conditions of zero visibility. He even travelled to England during the War to help the British implement GCA radar, and saw the War first-hand as the English were experiencing it, something few American scientists ever did.

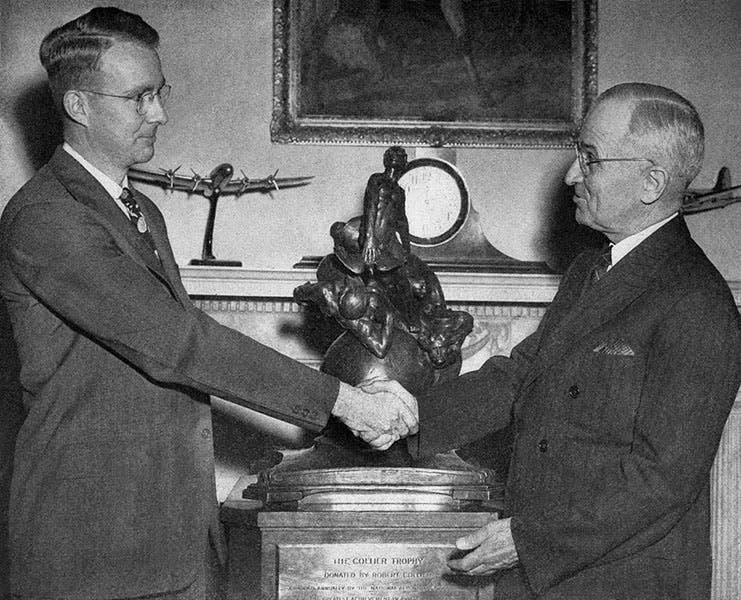

In 1943, Alvarez joined the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos and worked on developing the explosive lenses that were used to implode the plutonium bomb, and the tricky detonator system that fired the explosives. He even travelled to Tinian in the Marianas and rode in the plane accompanying the Enola Gay to Hiroshima on that fateful day of Aug. 6, 1945, taking instrument readings to record details of the blast. After the war, working at Berkeley, he developed a massive hydrogen bubble chamber that allowed for the detection of a myriad of sub-atomic particles, and this earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1968. All this work was done well before 1961 and should have guaranteed Alvarez his cover spot on the Jan. 2, 1961, issue of Time. Perhaps being left off the cover only inspired him, for there were great things to come in his career, even though he was 50 years old in 1961 and well beyond the age at which most physicists have exhausted their creative powers.

Alvarez, however, was unstoppable, and in his later years he did what he called "scientific detective work." After the Warren Report on the assassination of President Kennedy was issued, and a bevy of experts reported to Congressional committees that the Report was wrong and there must have been several shooters, it was Alvarez who spent weeks analyzing the Zapruder film frame by frame and was able to show that the motion of Kennedy's head was physically consistent with two shots fired from the rear, and that the argument that the backward movement of Kennedy’s head was evidence of a shot from the front was both insupportable and unnecessary. He also took a muon (mu-meson) detector to Giza in Egypt and “photographed” the second pyramid using cosmic rays, concluding that, except for the chamber found by Giovanni Belzoni in the 19th century underneath the pyramid (where they set up their equipment), there is no other chamber within the pyramid itself.

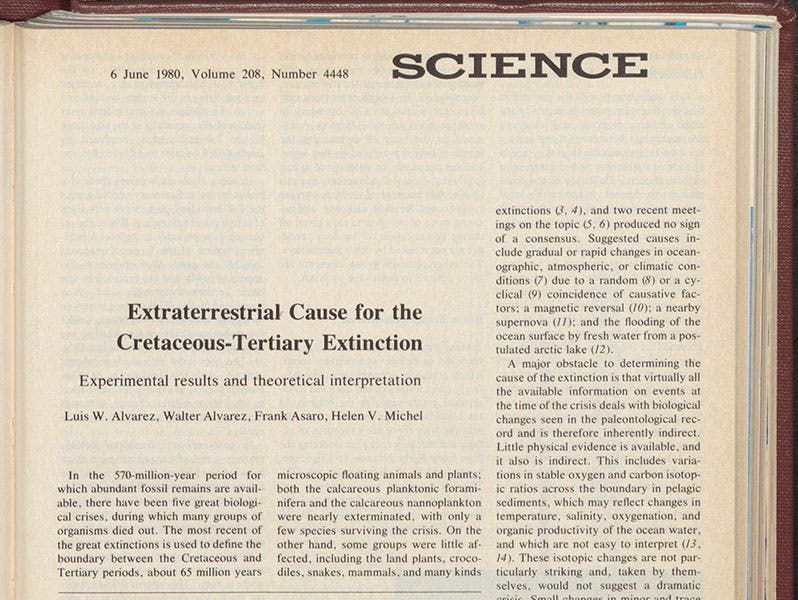

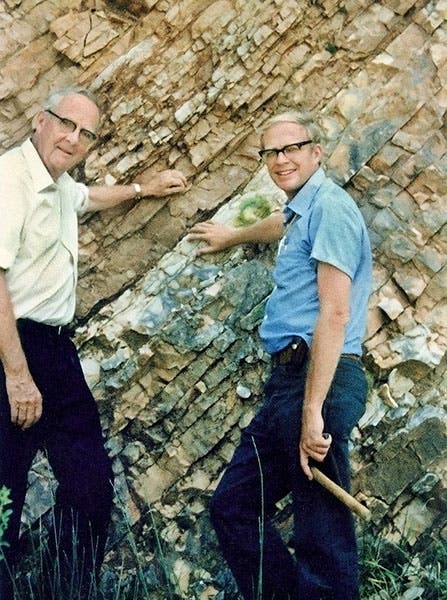

But Luis’s most famous bit of detective work came in 1979, when his son Walter, a geologist, asked Luis's advice in explaining the curious composition of a layer of clay that was laid down 65 million years ago, marking the boundary between the Cretaceous and Tertiary periods (called the K-T boundary), and coinciding with the extinction of the dinosaurs. Drawing on his vast knowledge of physics, Luis suggested that Walter examine the sample for siderophiles (“iron-lovers”), elements that are reasonably common in meteorites but rare on the earth's surface. Nuclear chemists were brought in, and it was found that the sample contained about 300 times as much iridium as the layers of limestone above and below the clay. Within a year, Luis and Walter and the chemists published an article in Science, “Extraterrestrial Cause for the Cretaceous-Tertiary Extinction," which argued that the extinction was the result of the impact of a large (6-mile-diameter) asteroid, which disintegrated on impact and shrouded the earth with a dense cloud of (iridium-rich) dust which ultimately formed the layer of clay, and not incidentally, caused a wide range of extinctions. Although paleontologists strongly resisted the return of catastrophism to geology, Alvarez lived to see his ideas vindicated (he died in 1988). The impact theory, or the Alvarez hypothesis, is now the textbook explanation for the Cretaceous extinction.

The photo above shows Luis (left) and Walter at the K-T boundary site in Gubbio, Italy, the source of Walter's first sample of the clay from the K-T boundary.

If you wish to learn more about the remarkable life and career of Luis Alvarez, I highly recommend his autobiography, Alvarez: Adventures of a Physicist (Basic Books, 1987), which I re-read while writing this post. In addition to tales not discussed here, it also has quite a few photographs of Alvarez, at MIT, Berkeley, Los Alamos, Tinian, and with his family, that I could not find anywhere online, or I would have included some of them here.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.