Scientist of the Day - Mariner 9

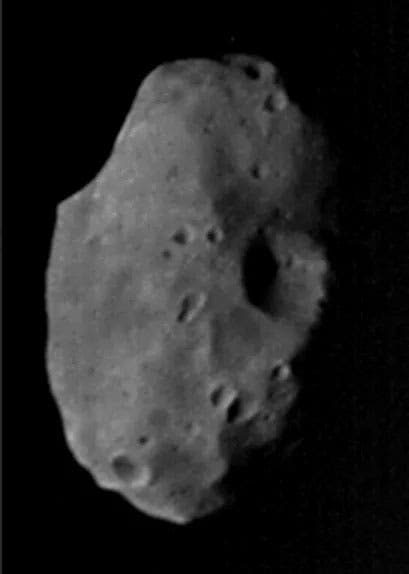

Mariner 9, an unmanned planetary exploration spacecraft, was launched May 30, 1971, from Cape Canaveral in Florida, headed for Mars. The mood at launch was intense, as 21 days before, its Mars-mate, Mariner 8, had failed to escape Earth and had burned up in the atmosphere. But Mariner 9's launch on an Atlas-Centaur rocket was successful, and it arrived at Mars on Nov. 14, 1971, after a journey of some 5 and a half months.

Mariner 9 had been preceded by Mariners 6 and 7, both of which had been sent to Mars in 1969. But those were fly-by missions that did not come very close to the Martian surface. Mariner 9, on the other hand, went into orbit around Mars, and in doing so, became the first spacecraft to be placed into orbit around another planet. It beat a pair of Soviet spacecraft to Mars by only a few weeks.

Mariner 9 was a huge success for NASA and for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, which built the spacecraft and managed it in orbit. The first challenge was immediate, as Mariner 9 arrived in the middle of a massive planet-wide dust storm, and could not even see the Martian surface. Since one of the primary mission goals was to map the surface of Mars, this could have been catastrophic. Fortunately, JPL was able to reprogram the mapping, and delay its start until January, by which time the dust had settled and the surface was visible again. Interestingly, the two Soviet probes were pre-programmed and could not be reprogrammed, returning images of nothing but dust.

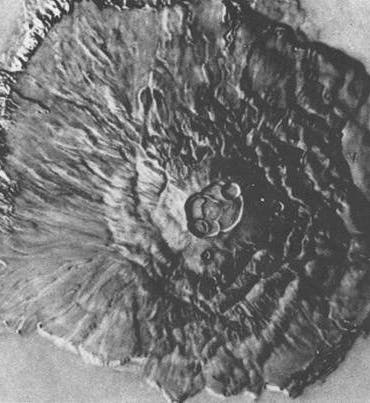

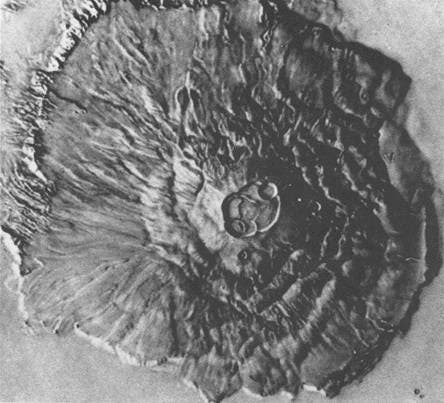

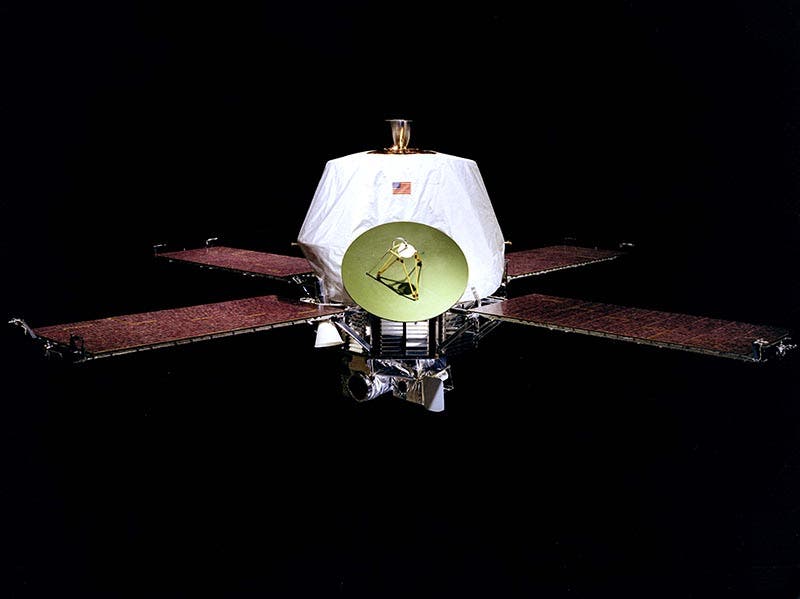

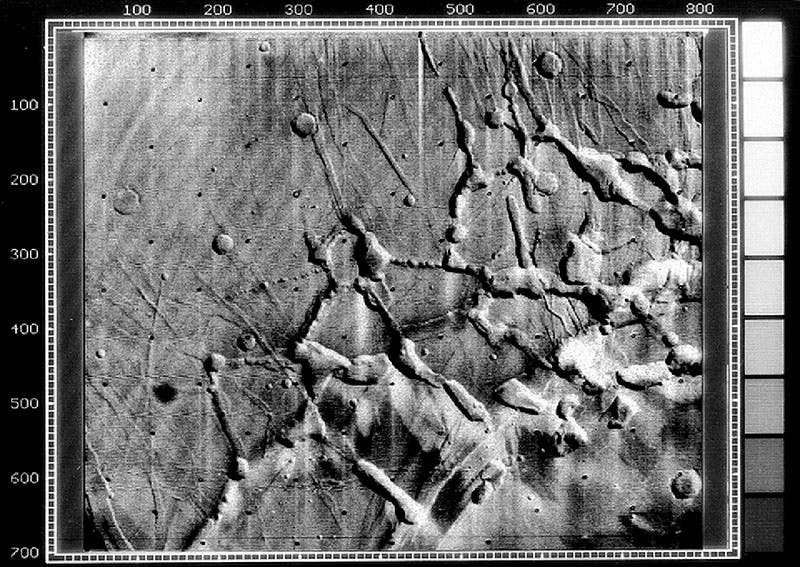

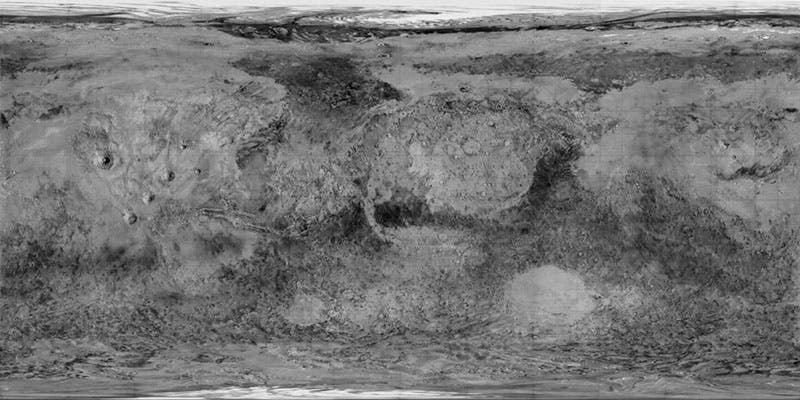

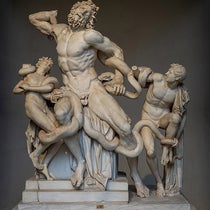

Mariner 9 had quite a few notable successes. It discovered the massive system of volcanoes in the Tharsis region of Mars, most notably Olympus Mons (first image), which is about the size of Missouri and 13 miles high (Mariner 6 or 7 could easily have seen this volcanic plateau, but they flew over a different part of the planet). Mariner 9 discovered the great equatorial canyon system, some 2500 miles long, which was later named Valles Marineris, the Valley of the Mariner, after Mariner 9 (here is a link to a famous Viking photo of this spectacular landform). Mariner 9 took the first close-up images of the Martian moon Phobos, only 16 miles long (third image). And it returned over 7300 greyscale images of the Martian surface, covering some 85% of its total area (fourth and fifth images).

The success of Mariner 9 is often obscured by the achievements of the two Viking Mars missions of 1977-79, both of which sent landers down to the Martian surface. Out of curiosity, I just looked through the collection of images I used for my classes when I taught the history of planetary exploration, and all of them were Viking or later, with only a single Mariner image among them, and that one was not from Mariner 9, but from Mariner 4, a flyby photo that revealed that there are no canals on the Martian surface. But Viking 1 and 2 would have been impossible without Mariner 9 and its photo-mapping. Mariner 9 deserved more appreciation from me, and still does, from all fans of the Red Planet.

For decades, they (NASA/JPL) have been saying that Mariner 9, its orbit decayed, would crash into Mars in 2020, or perhaps 2022. But no one is now saying that it actually did so. Perhaps it is hanging on a little longer.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.