Scientist of the Day - Mary Toft

Mary Toft, an English country maidservant, died Jan. 13, 1763, at the age of about 62. She lived in the market-town of Godalming in Surrey, southwest of London. Ms Toft was quite well known at the time of her death, unusually so for a woman of her station in life. Her fame stemmed from an incident, or a series of 15 incidents, that began in September 1726. According to various weekly tabloids, Mary, after a miscarriage, remained pregnant, and gave birth to some 15 rabbits, or parts of rabbits, over the course of the next two months. She was attended to by an obstetrician from nearby Guildford, John Howard. The bunnies (those that were whole) were, alas, stillborn, but nevertheless, they were rabbits, not what you would ordinarily expect from a country lass. The word spread rapidly, so the later of these leporine deliveries were personally witnessed by a variety of reputable doctors and surgeons, including one come down from London, King George I's personal surgeon, Nathaniel St Andre. By this time, Mary had been moved to Howard’s surgery in Guildford

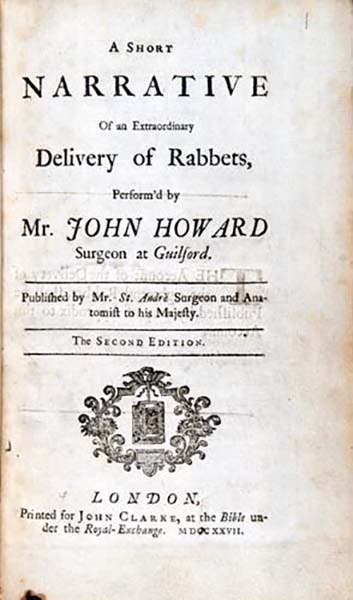

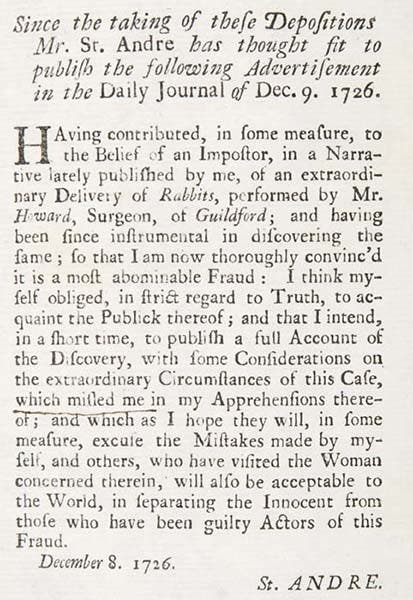

Although a few onlookers were skeptical as to what they were supposedly seeing, St Andre and some of his colleagues were not, and on Dec. 3, 1726, St Andre published A Short Narrative of an Extraordinary Delivery of Rabbets, in which he marveled at the unusual births (third image). As fortune would have it, by the time this treatise appeared, Mary had been transferred to London and asked to continue bringing rabbits, preferably live ones, into the world. When she could not comply, Mary finally confessed, in writing, that it was all a hoax. She confessed on Dec. 7, and again on Dec. 8, and on Dec. 12, each time naming a different accomplice as the rabbit smuggler. Poor St Andre took out ads in several papers (fourth image) trying to explain how he had been fooled by the imposturing Aunt Wiggly, but his career as the King’s surgeon was thoroughly shot. A caricature of St Andre made at the time carried the caption: “Rabbit Doctor” (fifth image)

Mary spent some time in jail, but she was soon released and sent packing, as no member of the medical profession wanted her around as a reminder of their gullibility, especially after satirist William Hogarth let the cunicular physicians have it with both barrels in a splendid cartoon (first image).

The University of Glasgow Library Special Collections has a great treasure trove of "Toftiana" related to the case, much of it on display on this webpage, and some of which we reproduce in this post. It is fascinating to read through; it even includes Ms Toft’s handwritten confessions. It would be interesting to know how all this ephemera was assembled; such material rarely survives for long, so someone at the time must have made quite an effort to collect it. We appreciate their having done so.

St Andre might have been done as a surgeon, but he generated at least one more historical wave. One of those present at the rabbit parturitions in Guildford was Samuel Molyneux, an Irish politician and amateur astronomer; it is not clear whether Molyneux knew St Andre before 1726, or whether they met at the bunny trials. Whatever, they remained in touch. Molyneux married the daughter of the Earl of Essex and acquired a palatial home in Kew Gardens, known as Kew House, where he set up his telescope and served in the House of Commons. When he collapsed in Parliament in 1728, St Andre was summoned, and he accompanied Molyneux home to Kew House. In a matter of days, Molyneux was dead, and St Andre had run off with Molyneux’s wealthy wife, whom he soon married. St Andre was accused of murder in print by a Molyneux relative, but nothing ever came of the charges.

After her return home, Mary Toft was not heard from again, at least not in the historical records I have access to. A portrait was painted in 1726, probably in London, and later reproduced in black and white; the location of the original portrait is not known (second image). She did not look too happy with the results of her successful attempt to fool at least some of the medical establishment.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.