Scientist of the Day - Maximilian Hell

Maximilian Hell, a Hungarian astronomer and Jesuit priest, was born May 15, 1720. Hell was head of the Vienna Observatory from 1756 on. While there, he published an Ephemerides for the meridian of Vienna (1760), which we have in our collections. In 1769, he headed for Lapland with an assistant to make precise observations of the passage of Venus across the Sun on June 3 of that year. Venus makes such solar crossings regularly but not frequently – twice every hundred years, eight years apart. But this was the first time that scientists were ready with telescopes and chronometers to record the "transit", as the passage is called. In addition to the stay-at-home observers at Greenwich and Paris observatories and Hell in Lapland, Captain Cook and Joseph Banks built an observation post at Tahiti, Guillaume Le Gentil travelled to India (where it was cloudy!), and Jean-Baptiste Chappe d'Auteroche was in Baja, California. The hope was that, by triangulating on Venus and the Sun from different positions on Earth, the distance to the Sun (what astronomers call the 'astronomical unit') could be calculated with great exactness. Hopes were too high, in this case; it turned out that it was very hard to pinpoint just when Venus enters the Sun's disk. But the transit of Venus of 1769 remains famous as the first international cooperative scientific enterprise, and Hell was its northernmost cooperant. He published an account of his transit expedition in 1770, but we do not have this in our library.

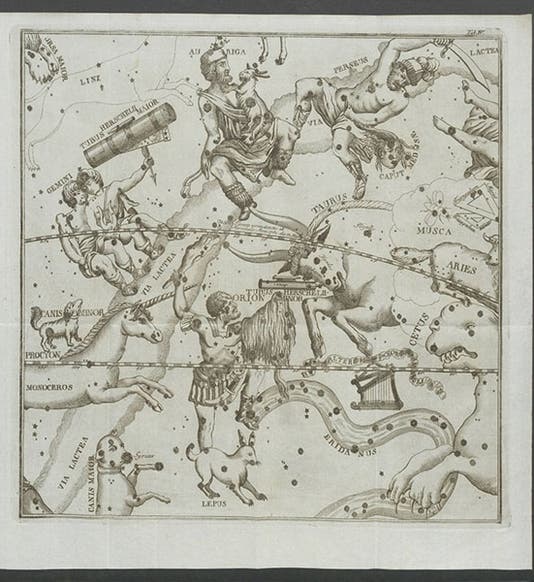

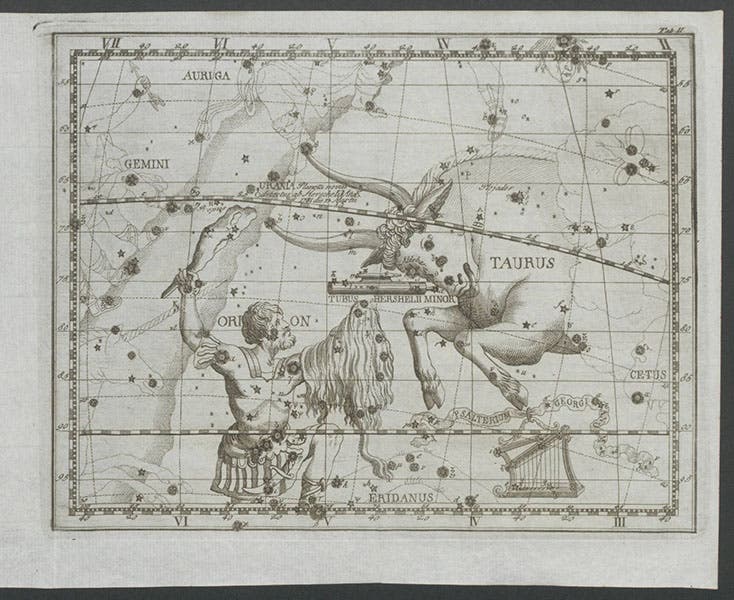

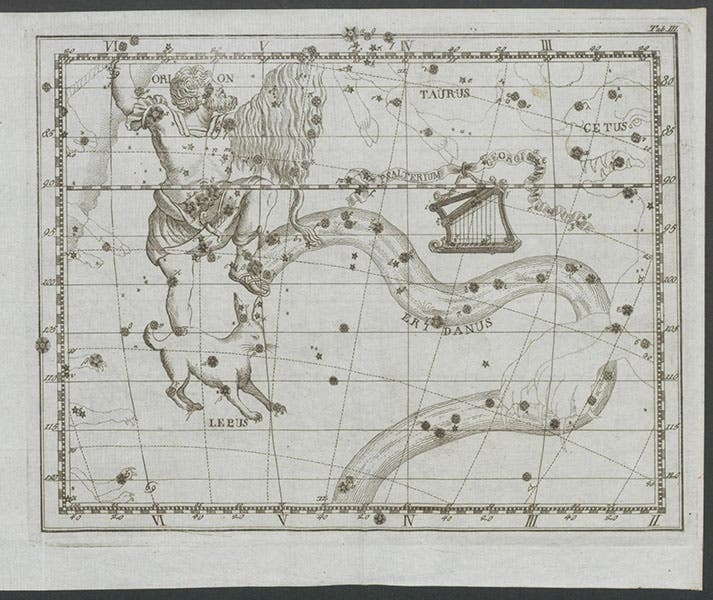

Hell was also an inventor of constellations. In 1789, he formed three new constellations out of some outlying stars in the vicinity of the constellations Auriga, Gemini, Taurus, and Orion. Two of these were named after telescopes, large and small reflectors, made by William Herschel, and one was a harp, George's Harp, named after George III, King of England, and Herschel’s patron. The Latin names were: Tubus Hershelii maior (third image), Tubus Hershelii minor (fourth image), and Psalterium Georgii (fifth image).

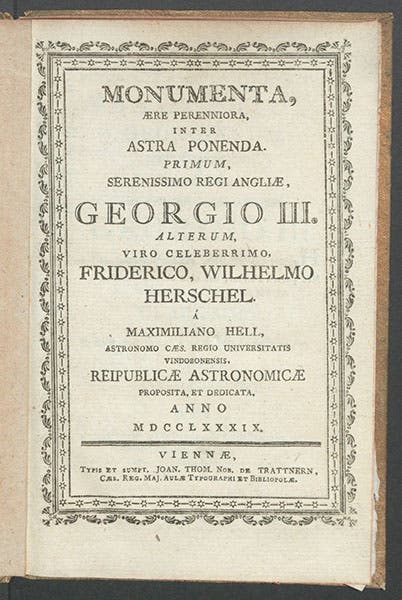

Hell announced his constellations in a pamphlet called Monumenta, aere perenniora, inter astra ponenda (1789), which we acquired just last year (second image). It has four engraved plates, all of which we reproduce here; a plate for each individual constellation, and one that shows all three at once (first image). Our Library is quite proud of its collection of star maps and atlases, and the addition of Hell's publication makes it just a little bit better.

Herschel had used his Tubus minor to discover a new planet, Georgium sidus (Uranus) in 1781. The star chart of Tubus minor (as well as the chart showing all three constellations) commemorates the discovery with a printed phrase right next to the location where Herschel first spotted Uranus. It says: Urania: Planeta novus detectus ab Herschel 1781 die 13 Martii – “Urania: new planet detected by Herschel on Mar. 13, 1781,” and we show it to you in a detail of the third image (sixth image).

Unfortunately, the picture of Tubus minor that Hell includes on his chart looks nothing at all like Herschel’s actual small telescope, a 7-foot Newtonian reflector, through which the new planet first swam into Herschel’s ken. You can see Herschel’s actual Tubus minor as the first image in Herschel’s debut appearance as a Scientist of the Day. Sadly, and not surprisingly, Hell’s new constellations had a short-lived popularity; although Johann Bode adopted two of them for his Uranographia (1801), they eventually disappeared from later star atlases, and today none of the three are included among the 88 officially accepted constellations. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.