Scientist of the Day - NASA

NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, was signed into life on July 29,1958, when President Eisenhower approved the National Aeronautics and Space Act. The agency began functioning on Oct. 1, under the directorship of Administrator Keith Glennan.

The immediate impetus for the formation of NASA was the Soviet success in launching Sputnik 1 into orbit on Oct. 4, 1957, an in-your-face indicator that, in the burgeoning space race, the U. S. was in a distant second place.

There was an existing agency that had done quite well in bringing the U.S. into aeronautical supremacy during the two World Wars and the post-war period. NACA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (pronounced N-A-C-A), had been founded in 1915, and over the years, it had established 3 research laboratories – Langley Aeronautical Laboratory in Virginia, Ames Aeronautical Laboratory in Califonia, and Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in Ohio – and in the early 1950s, was busy testing rocket planes like the X-1. But rocket research and launchings were being conducted by all three branches of the military, Army, Navy, and Air Force, all independently, and there were not many successes to point to.

Eisenhower’s advisors told him that our efforts in space needed to be under the aegis of one agency, and that it should be a civilian agency. And so NASA was born. It subsumed the entirety of NACA with all its personnel, including all three aeronautical labs. I am not sure how the three military branches felt about losing their independence in matters of rocketry – probably not kindly at all – but it turned out well, since the story of NASA is considered a success story by most historians.

NASA's first home was, of all places, the Dolley Madison House on Lafayette Square in Washington. That must have been a cozy beginning for the agency, especially since various groups had been trying for years to tear it down to make way for a new office building. It would later be saved by Jackie Kennedy, but this was after NASA moved on to larger quarters. The house still stands today. Hopefully there is a historical marker somewhere that notes this was NASA's first headquarters, but I could not find one online.

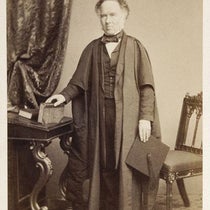

The first director, Keith Glennan, came to NASA from Case Western University in Cleveland, where he was president, and he would serve only 2 1/2 years, but it was an auspicious beginning. Glennan managed to bring Jet Propulsion Lab, heretofore run by Caltech, into NASA's fold in December of 1958, and he also scooped up the Army's rocket facilities in Huntsville, Alabama, bringing along Wernher von Braun in the process. And Glennan established the Goddard Space Flight Center just north of Washington, in Greenbelt, Maryland, in May of 1959, providing us with our first space flight laboratory.

If one measures NASA’s progress by rocket launches, things were not quite so rosy, as it took a while before successful launches began to outnumber unsuccessful ones

Pioneer 1, NASA’s first official launch, went up on Oct. 11, 1958, and while it got off the launch pad, it fell far short of its mission to orbit the Moon, reaching an altitude of only 70,000 miles and falling back to burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere. The firts real success came with Pioneer 4, launched toward the Moon on Mar. 3, 1959; it was the first spacecraft to escape Earth’s gravitational pull and go into orbit around the Sun. Its backup, or perhapsr replica, is on display in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington.

NASA's principal early interest was in manned space flight, and within a week of opening its doors at Dolley Madison House, NASA established Project Mercury, which would select 7 astronauts for manned suborbital and orbital flights. The program was announced to the public in December of 1958, and by spring, Alan Shepherd, John Glenn, and five others with the "right stuff" were being introduced to the press corps in Dolley Madison's ballroom.

Glennan had to resign his post when his Republican President was succeeded by a Democratic one, John Kennedy. Fortunately, NASA did not miss a beat, as Kennedy appointed James Webb as NASA's second Administrator, to carry through on Kennedy’s promise, made publicly in the summer of 1961, to send a man to the moon and bring him home safely before the decade was out. Webb not only launched the Apollo program, but saw it through almost to the Apollo 11 landing, but not quite, as Lyndon Johnson decided not to seek a second full term, the Republicans came back in, and Webb had to move on.

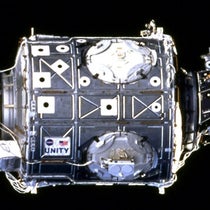

But we are celebrating the birthday of NASA, not her entire life, and we must leave her as a 3-year-old, hoping the opportunity arises on some future day to look at the age of Apollo, Voyager, Viking, the Space Shuttle, and the Hubble Space Telescope.

The closest artifact to me, representing the first three years of NASA, is the capsule of the second Project Mercury flight, named Liberty Bell 7, which, after a successful suborbital flight with Gus Grissom aboard, sank during recovery. It was lifted from the ocean bottom in 1999, carefully cleaned and restored, and is now on display at the Cosmosphere in Hutchinson, Kansas, where I have seen it twice. I wrote a post on Liberty Bell 7 just two years ago.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.