Scientist of the Day - New York Crystal Palace

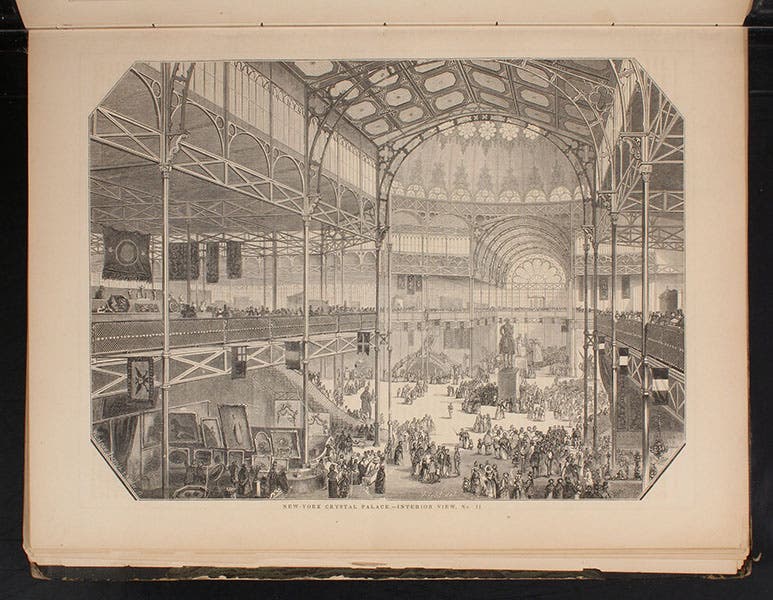

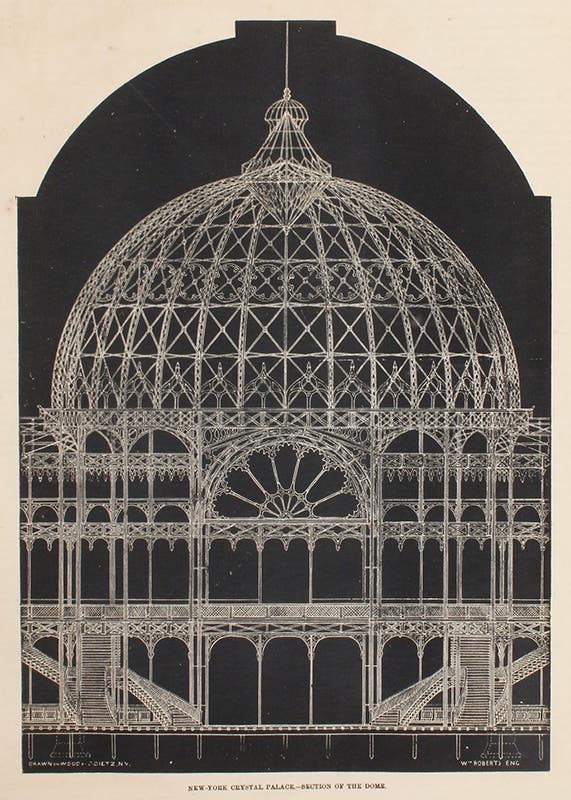

The New York Crystal Palace exhibition, America's first world's fair, opened to the public on July 14, 1853, with President Franklin Pierce doing the honors. More properly known as the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, it was inspired by the success of the very first world's fair, London's Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851. Plans for a New York version began immediately, and, disinclined to deviate from a proven winner, New York built a Crystal Palace of its own of iron and glass, at 6th Ave and 40th-42nd street at the site of modern Bryant Park. We have in the Library the Official Catalogue of the New York Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations (1853), which is an unillustrated listing of all the exhibitors, as well as a folio after-the-fair picture book, The World of Science, Art, and Industry Illustrated from Examples in the New-York Exhibition, 1853-54 (1854). The latter work includes three engraved views of the palace interior (we show one as our second image), and another white-on-black engraving showing the ironwork in the dome (third image).

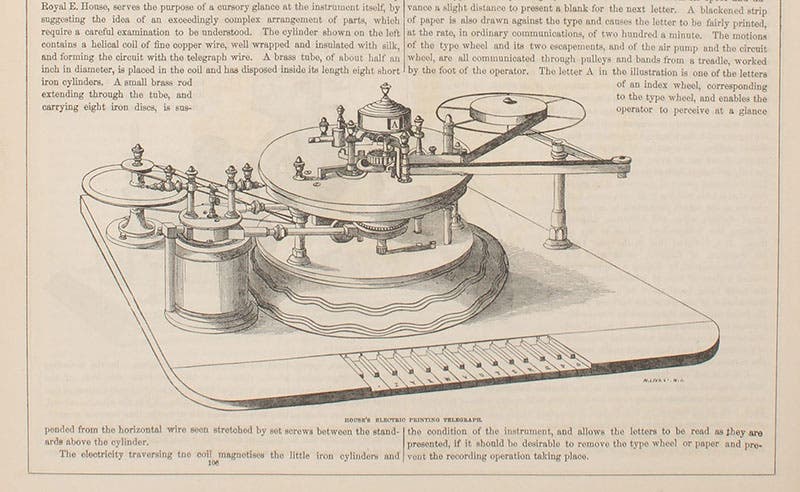

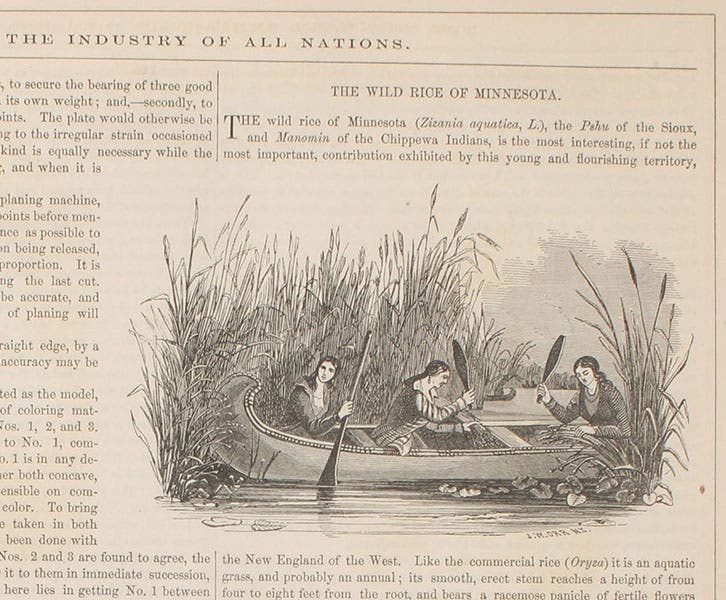

Most of the items on display were the usual froufrou that dominated the early fairs – glassware, metalwork, ceramics, dinnerware, and the like. I like the display of Minnesota wild rice, or at least the engraving included in World of Science (fifth image). But there was a fair amount of science and technology tucked in, and many of the technological devices had American origins. In fact, it was at this fair that American inventiveness really showed itself for the first time. It was not as evident as it would be at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876 or Chicago's World's Columbian Exposition in 1893, but it was there. Royal Earl House’s innovative printing telegraph, an American invention, with its piano-style keyboard, was on display, and was illustrated in The World of Science (fourth image). Henry Fitz, the first American telescope maker of any repute, won a medal for one of his refractors (you can see a number of Fitz refractors in a post on Fitz that we wrote in 2019), and John Whipple showed his daguerreotypes of the Moon, taken at Harvard College Observatory, the very first example anywhere of astrophotography, and he won a medal as well. You can see the daguerreotype displayed in 1853 as the first image of our post on Whipple.

The most telling evidence that American science had come into its own was a display by the U.S. Coast Survey. This was the first government-sponsored scientific office in our country, under the supervision of Alexander Dallas Bache, and for ten years it had been surveying the coast, taking soundings, establishing latitudes and longitudes for major port cities, and publishing charts and maps. Their display, a technical one, would likely not have impressed you and me as much as the large steam engines that blustered inside the Crystal Palace. But Charles Lyell, eminent British geologist and a member of the British delegation to New York, declared that the Coast Survey display was the highlight of the exhibition, demonstrating that the Yanks had finally figured out what science was all about. However, the Coast Survey did not impress the editors of The World of Science, for they include only a short unillustrated entry on the survey.

Most short articles on the 1853 exhibition like to point out that Elias Otis demonstrated his first safety elevator here, dramatically cutting the rope holding it high above the floor while the safety devices prevented its descent. Indeed, this demonstration did take place, but it was not really part of the exhibition – it was a one-time stunt dreamed up by Phineas T. Barnum in 1854 to drum up attendance at the Palace.

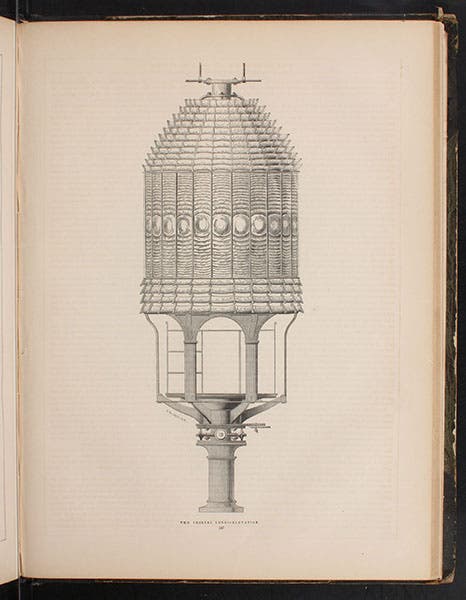

One of the items on display in the New York Crystal Palace was a first-order Fresnel lens, a thirty-year old French invention that, at least in Europe, had revolutionized the effectiveness of lighthouses by providing them with much brighter beams. Two Fresnel lenses had been installed in New York Bay in 1838, but none since, and indeed the New York Crystal Palace lens was the first one that anyone other than a lighthouse keeper had ever seen close up. As an item of display, it was quite a success, since Fresnel lenses are indeed as worthy of admiration as any Waterford crystal. The Crystal Palace lens would head down to Cape Hatteras in North Carolina after the Exhibition. There is a full-page engraving of the lens in The World of Science, Art, and Industry Illustrated (sixth image). We also have written a post on Fresnel, where the lead image is a modern color photo of a first-order Fresnel lens very similar to the one on display in New York in 1853. Isn’t it glorious? Fresnel lenses are right at the top of my list of favorite scientific artifacts.

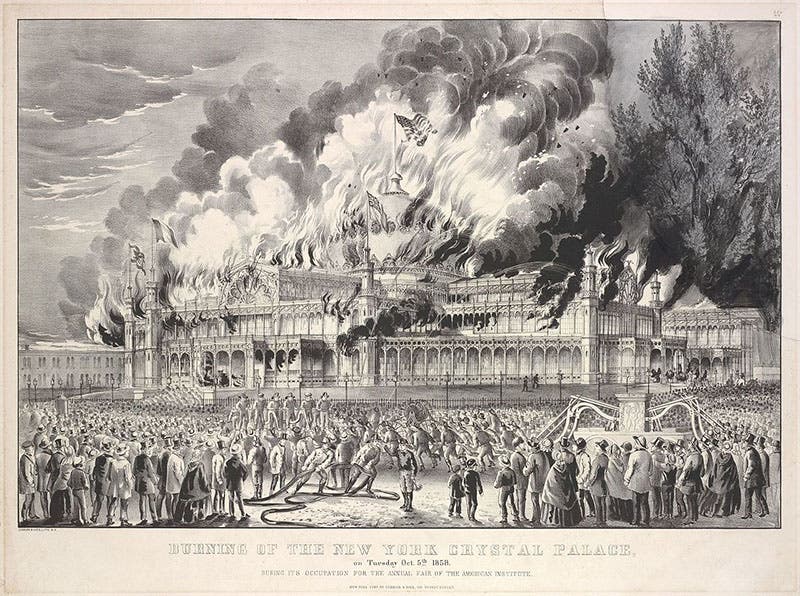

The fair closed in November 1854, and the building was sporadically occupied by local trade fairs until Oct. 5, 1858, when the iron and glass building somehow burned to the ground in less than 30 minutes. Currier and Ives later recorded the disaster with a lithograph (seventh image). In addition to the palace itself, many artifacts were lost, including the very first steam road carriage built by Richard Dudgeon in 1857 (see second image at the link). There is no trace of the Palace or the exhibition grounds surviving today.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.