Scientist of the Day - Niccolo Cabeo

Niccolò Cabeo, an Italian natural philosopher, was born Feb. 26, 1586. Cabeo was a Jesuit, and like many Jesuits, he was interested in magnetism, because magnetism seemed to demonstrate the existence of occult properties, the hidden propensities of things to cause effects in other objects without an obvious means of action. Since a lodestone, or natural magnet, could magnetize a piece of iron, and then cause the iron object to move toward the lodestone, and itself to move toward the iron, this seemed to be a wonderful manifestation of occult properties. And the Jesuits were fascinated by occult effects.

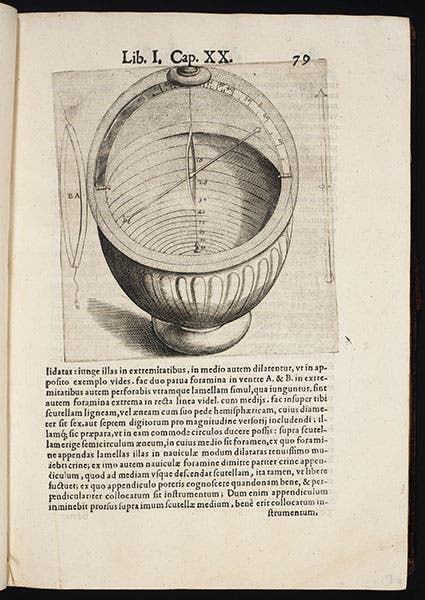

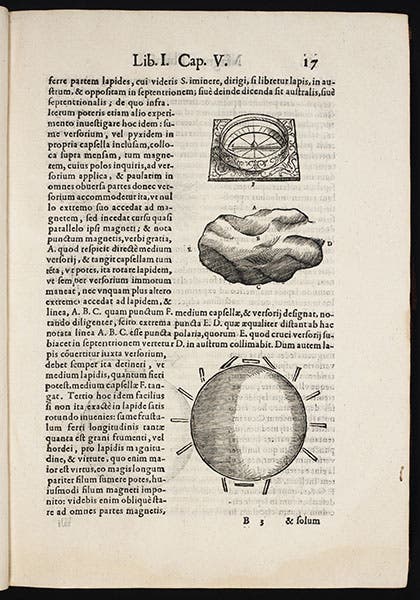

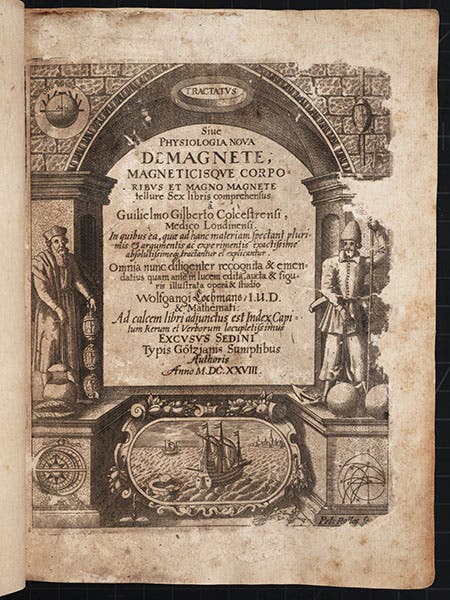

In 1629, Cabeo published Philosophia magnetica, the first extensive study of magnetism since the Englishman William Gilbert – most decidedly not a Jesuit – had published his De Magnete (1600), in which he demonstrated an experimental approach to the study of magnetism. Gilbert also proposed the novel idea that the earth itself is a giant magnet, and that a compass does not point toward the North Star, but rather towards the earth's magnetic north pole. Cabeo’s book is moderately well-illustrated, with woodcuts showing lodestones, magnetic attraction, and even an engraving of a dip needle (second and third images).

Cabeo seems to have admired Gilbert's work, but he disagreed with Gilbert on a number of points, especially when Gilbert was critical of the Aristotelian approach to natural philosophy that had been adopted by most of the Jesuits. And he definitely did not agree, as Gilbert had concluded, that the earth’s magnetism caused it to rotate on its axis.

It used to be thought that Cabeo's work on magnetism was original, but not that long ago (2006), a scholar rediscovered a manuscript of the 1580s by an earlier Jesuit, Leonardo Garzoni, who had done some quite original work on magnetism before Gilbert, but whose treatise had never been published. Cabeo discussed and praised Garzoni in his book, but he did not mention that huge chunks of his Philosophia magnetica had been lifted verbatim from Garzoni's treatise. Plagiarism was not that uncommon in early modern scholarship, but such blatant and extensive plagiarism was a bit unusual, even for a 17th-century Jesuit.

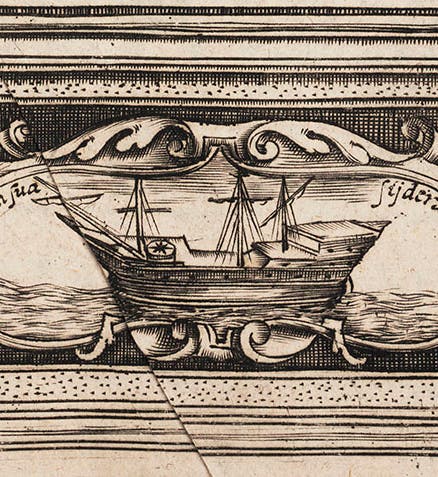

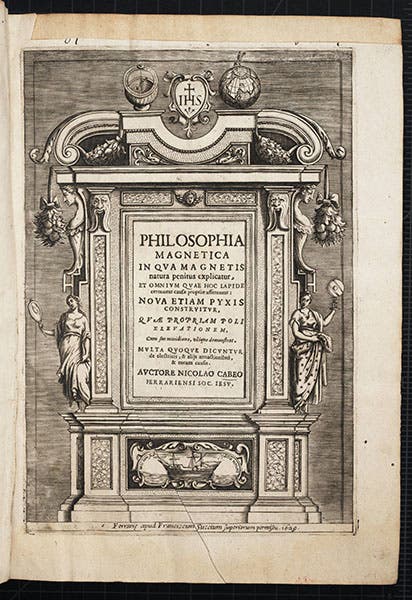

The engraved title page to Cabeo’s book (fourth image) is not that exciting, as illustrated title pages go, although one of the instruments, a dip needle, reappears at the top of the engraving). But there is an interesting emblem at the bottom (first image), showing a ship with a huge compass on its foredeck, and the motto: Hic iam sua sydedra norunt, “Now here they have come to know their own stars,” a clever way of suggesting that a compass allows the navigator to have his own North Star on his ship. Now that we know Cabeo’s scholarly propensities, it should come as no surprise that Cabeo borrowed the emblem from another source, in this case, the engraved title page of the second edition of Gilbert’s De magnete (1628), which had come out just the year before (fifth image), and modified it just enough, adding a motto and moving the compass onboard ship, so that the inspiration was not obvious. The motto, incidentally, comes from Virgil’s Aeneid. We have all three works discussed here in our History of Science Collection.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.