Scientist of the Day - Nicholas Chevalier

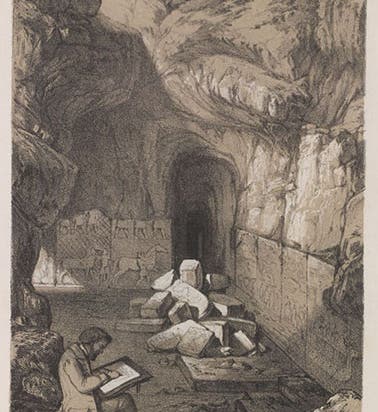

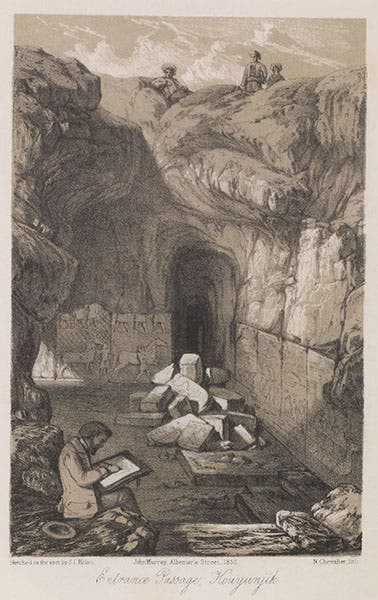

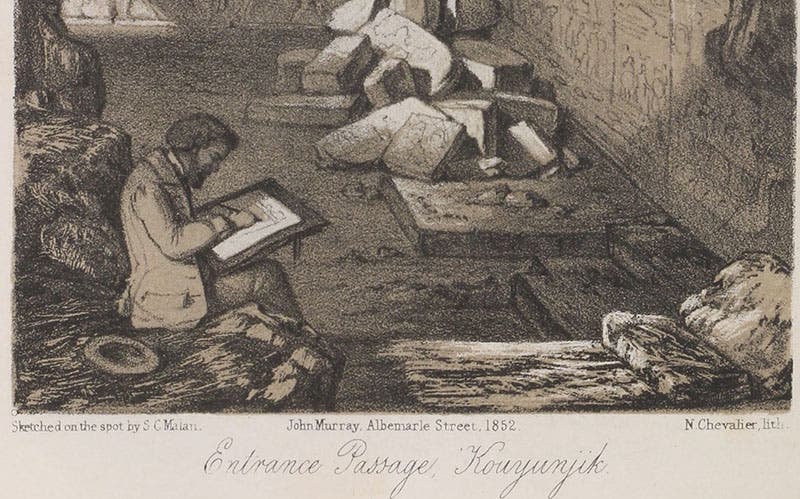

Nicholas Chevalier, a Russian/English/Australian lithographer and landscape artist, was born May 9, 1828. I first ran across Chevalier when I was working on an exhibition on science in the age of lithography (Crayon and Stone, 2013). Henry Layard, an English archaeologist, had been the first to discover the remains of the Assyrian empire, and he published a book in 1853, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, that was illustrated with several rich tinted lithographs, such as our first image, showing an entrance passage to a ruin at Nineveh. Chevalier did those lithographs. A detail of the first image shows not only his lithographic technique, but his signature. You can see two more of his Nineveh lithographs – the best two, in fact – at our post on Layard. Chevalier had come to London from St. Petersburg in 1851 and earned a living for a few years as an illustrator and lithographer. If he did illustrations for any other books in our collection other than Layard's book on Nineveh, I am not aware of them.

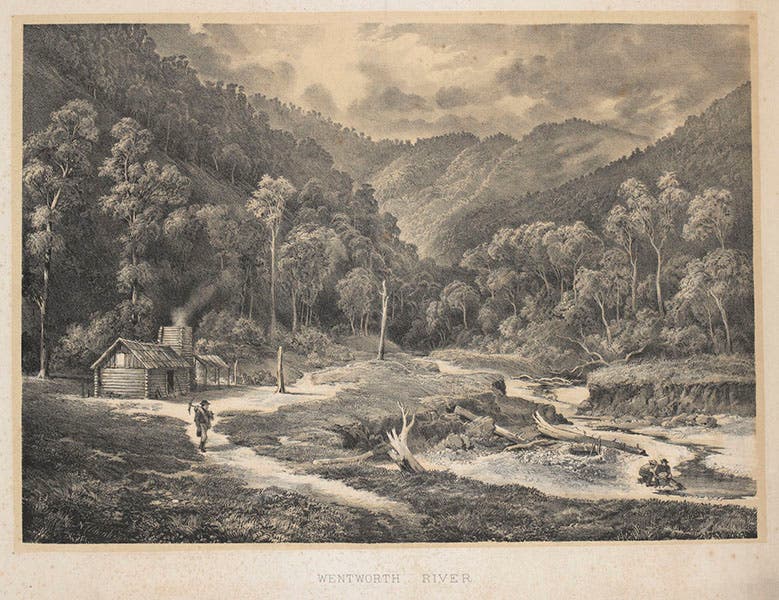

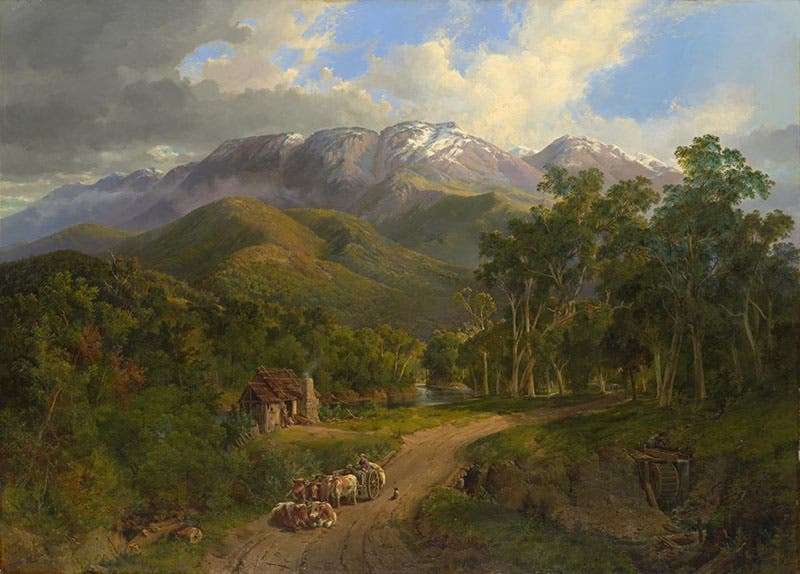

In 1855, Chevalier headed for Australia, at first continuing to work as a lithographer, learning the art of chromolithography (printing in colors on stone), and becoming quite adept, as we see from a sample titled “Wentworth River” (fourth image). But he also began to paint original works of art, mostly landscapes, and he soon acquired a following and some critical acclaim, which prompted him to change his career. Perhaps his most important early painting was The Buffalo Ranges, executed in 1864; it won a competition at the National Gallery of Victoria, which acquired the painting, and where you may see it today (fifth image).

It would seem that Chevalier was striking out in the same direction as the Rocky Mountain School of landscape painters in the American west, although there is no known connection between the likes of Thomas Moran and Thomas Hill and Chevalier's Australian school. Another early painting that I like is Pulpit Rock at Cape Schrank, done sometime in the early 1860s, and now in the Art Gallery of New South Wales (sixth image).

In 1865, and again in 1868, Chevalier visited New Zealand and made some watercolor sketches, which he later turned into oil paintings. We include here a watercolor of Cook Strait (seventh image), and an oil painting that he did almost 20 years later, back in London (eighth image). As art historians have pointed out, Chevalier had no compunction about fusing several scenes and moving things around to achieve a better composition. The painting of Cook Strait is in the Museum of New Zealand, usually called Te Papa Tongarewa.

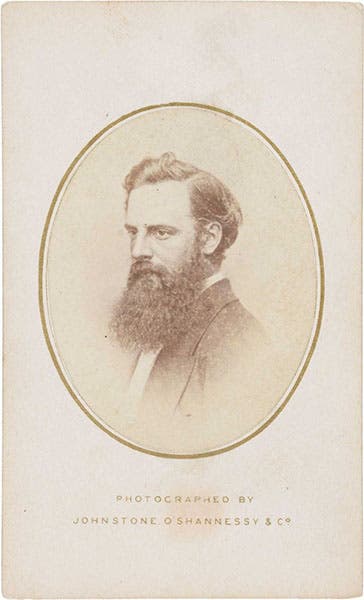

In 1868, England’s Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh, sailed into Australian waters as the commander of HMS Galatea, and sailed out with Chevalier on board. Chevalier had apparently become friends with Alfred, Queen Victoria's second son, when they were both in London, and their friendship picked up again onboard ship. They went to New Zealand, China, Japan, India, and Polynesia. Chevalier seems to have moved easily in royal circles – Queen Victoria later commissioned a portrait of Alfred from Chevalier – and no doubt part of the appeal was Chevalier’s extraordinary good looks. Self-portraits sometimes lie, but if the truth is even close to this (ninth image), he may have unhinged many a royal princess. Chevalier also had some musical talent, and he played second violin in a shipboard orchestra on the Galatea. The first violin chair was occupied by the Duke of Edinburgh. In the absence of further evidence, we will never know who was really the better bowman.

An exhibition of many of Chevalier's Australian paintings was mounted in 2011 in Victoria, and a catalogue was issued, but I have not seen it. I read a few reviews, and no one seemed ready to proclaim Chevalier as the Frederic Church of Australia. But he was a fine landscape painter. And I think his lithographs of Nineveh are extraordinary.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.