Scientist of the Day - Nicholas Wing

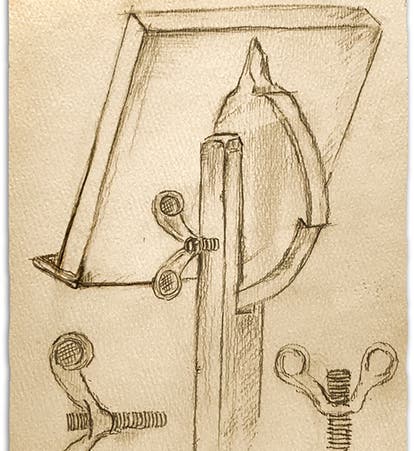

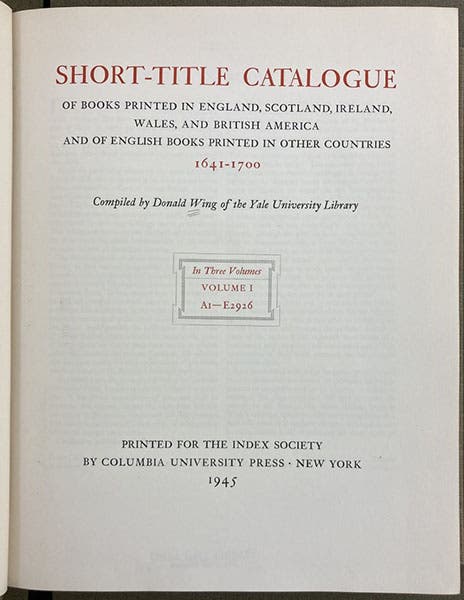

Design for a book stand with a flanged adjusting nut, designed by Nicholas Wing; Wing papers, Whistling Pig Pub and Archives, Kensington, London (whistpig.edu)

Nicholas Wing, an English inventor and book collector, was born on Apr. 1, 1638, in a bathing shack near the mineral spring at Tunbridge Wells, to parents taking the waters as part of the court of Charles I. Nicholas was raised and educated in London, where he showed an early aptitude, like Isaac Newton, for building mechanical contrivances, such as windmills and water clocks, in which he was indulged more by his mother, an ingenious homemaker, than his father, a barrister, then judge. His mother invented the self-rotating spit driven by heat from the fireplace, which Nicholas later replicated in his own house.

Neither of his parents had much of a library, so it is not clear where Wing picked up his penchant for books, but he frequented the book stalls around Old St. Paul's, and by the time he was 30, had a larger library than Robert Cotton, although Wing’s books were all printed, not manuscripts. Most of the funds for his book buying came from the estate of his father, who was a successful lawyer and judge but an imprudent streetwalker and was run over by a dray in Drury Lane in 1652, when Nicholas was but 14. In 1666, he was invited to become a Fellow of the Royal Society, not because of any scientific promise, but because he agreed to provide the books for the Society Library from his own surplus.

Wing's inventions are legion and well known. Since he was left-handed and, like all left-handers, had trouble using tools devised for righties, he invented left-handed calipers, left-handed scissors, a left-handed screwdriver, and even a left-handed lathe. His portrait, in the National Portrait Gallery (NPG), shows him, calipers in his left hand, about to measure an arc on a globe (second image). This portrait, oddly, was once thought to portray the young Isaac Newton, and is still so labelled in the NPG, although it looks nothing like Newton (and a great deal like Wing). He also invented a reflecting microscope, a mercury barometer that could be read upside down, and a cartridge pencil that used liquid graphite.

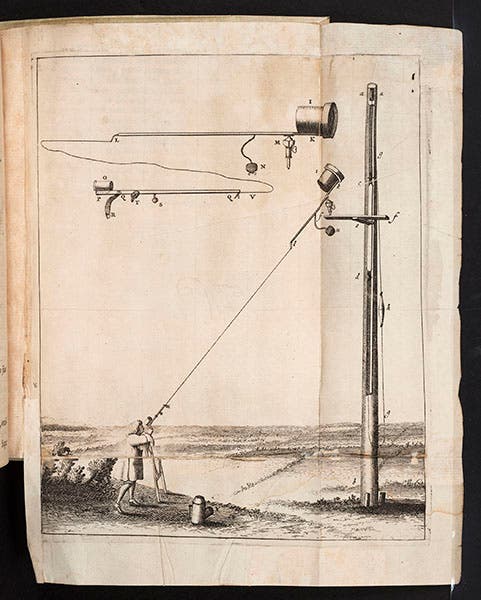

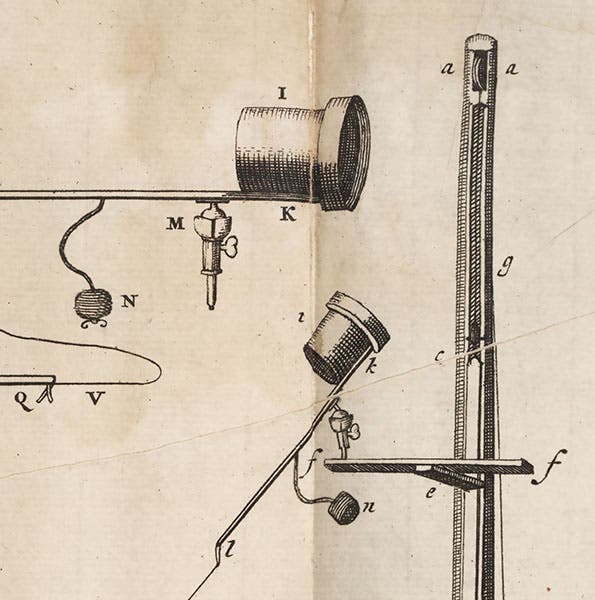

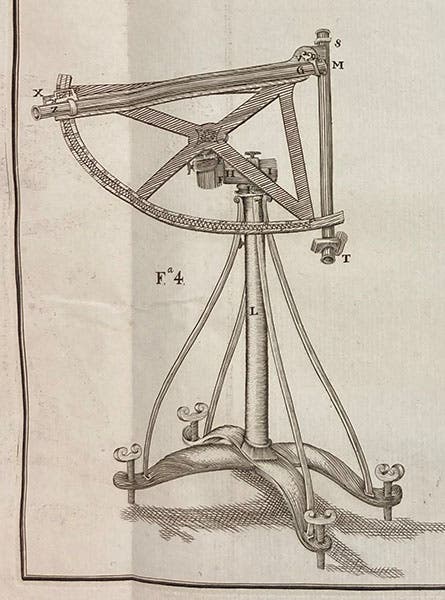

Wing’s most famous invention was one of his simplest. Apparently vexed at how time-consuming it was to change the tilt of one of the book-stands in his library, since it required a wrench, he invented a nut that could be tightened with just one’s fingers, simply by adding flanges to the nut. There is a sheet among his papers, a design for the back of his book-stand, that shows this invention quite clearly, with several insets providing the details of his invention (first image). We still call such fasteners "Wing nuts" in his honor. I was surprised to discover that many of his contemporaries misunderstood the invention and put the flanges on the bolt rather than the nut. We see such an instance in Christiaan Huygens’ engraving of his aerial telescope, where the aerial eyepiece was kept from moving by a Wing bolt that tightened against a ball-joint (third image, with a detail as fourth image). We see another use when Jorge Juan used flanged bolts to level his sextant (fifth image). Wing bolts are useful, but they are clamps, not fasteners. Wing nuts can fasten anything that an ordinary nut can fasten, but quicker, and it unfastens much more easily.

John Aubrey offered a description of Nicholas Wing in the biographical manuscript that we call his Brief Lives. It bears quoting:

He was lank and reedy, of a tilt; dark, brown hair, with a fair popping eie. His wit was huge, his humor mild; he took the tankard when offered and often. No book escaped his eie or purse; his house was fair filled to bursting with tomes. Yet he could lay his hand on any one of them within one turn of his spring watch, which he himself invented, and R. Hooke claimed as his own. He presented his inventions frequently to the R.S., but refused to prepare his thoughts or equipment in advance, so that merry chaos soon followed. Was oft seen sleeping in a chair he designed at the Whistling Pig off Bilbo Square.

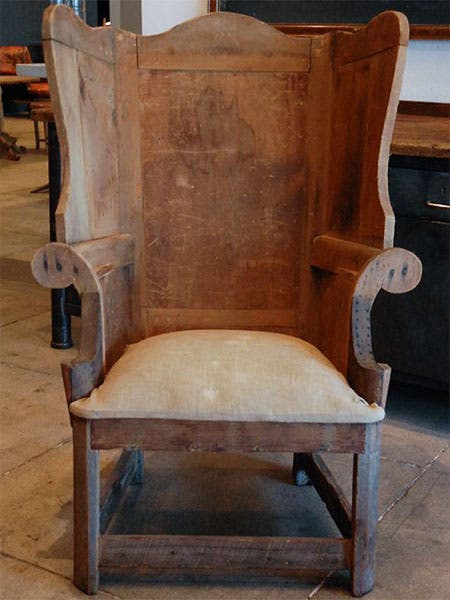

The chair Aubrey spoke of still survives in a London museum, where you can see his innovation – flanged panels to keep one’s head from flopping sideways; it was probably once upholstered (sixth image). The original Wing chair spawned tens of thousands of imitations. Aubrey also alluded to Wing’s propensity for giving unprepared lectures. Ever since, those who speak from the hip have been accused of “Winging it.”

The original reading chair of Nicholas Wing, the ancestor of all modern wingback chairs, now in the Lambeth Museum of Material Culture, London (guardian.com)

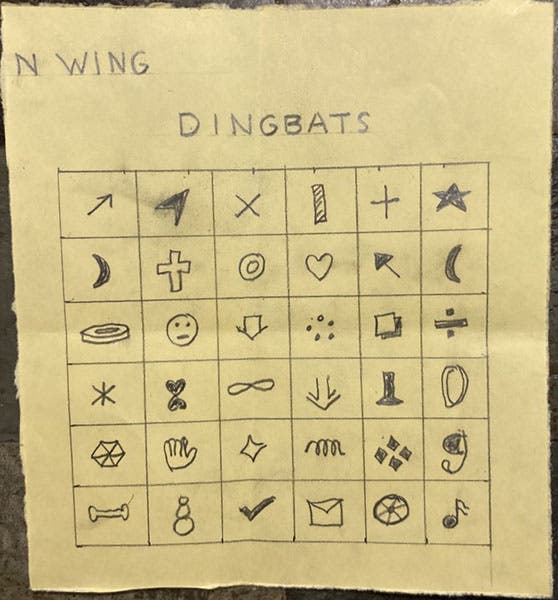

Since he was a book collector, Wing was interested in typography. From the advent of printing, printers had used odd, non-literal symbols as ornaments, on title pages and at the end of chapters. They were called dingbats. Wing thought there out to be a complete set of such fonts with their own type-box, and he made a chart of some of his proposed dingbats and sent it off to John Martyn, printer for the Royal Society (seventh image). The sheet still survives. Martyn cast most of these and quite a few more of his own design; he called them Wing Dingbats, which was eventually shortened to Wingdings. If you look at the font list in Microsoft Word, you will see three Wingding fonts. Microsoft claims to have invented these and to have coined the name from Windows and Dingbats, but we know better.

Scrap sheet of paper with ideas for Dingbats, in hand of Nicholas Wing; these proposed type fonts, later called Wingdings, were sent to John Martyn, printer to the Royal Society (royalsocietylondon.org)

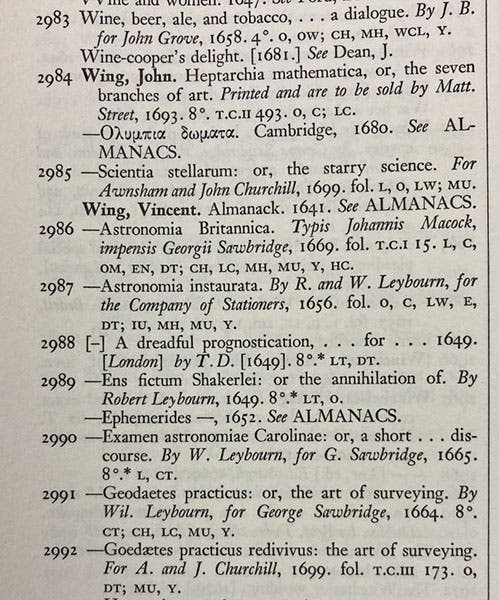

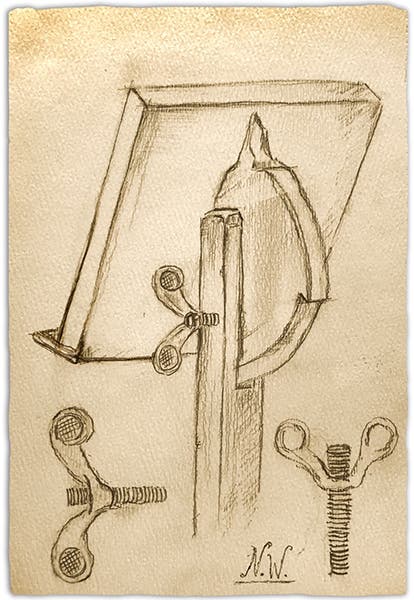

Wing’s enormous library, which included almost every book published in Great Britain in the last 60 years of the 17th century, passed intact to his descendants and heirs, becoming more valuable with each generation. Eventually, in 1945, the current owner and great-great…grand-nephew, Donald Wing, a librarian at Yale, published a 3-volume catalogue of the library, called Short Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England … 1641-1700, commonly referred to by librarians as “Wing” (eighth image). Every book from that period has its Wing number, and there are in regular use by rare book dealers and cataloguers. We show a column with books by two of Nicholas’ relatives, John and Vincent Wing, with the Wing numbers for those books at the left (ninth image). Nicholas does not appear, since he never wrote a book, which is probably why you have never heard of him, until now.

Nicholas Wing passed away in his chair at the Whistling Pig on his birthday, Apr. 1, 1701, and was buried in the pub graveyard with a few other patrons who never made it home. The pub later moved to Kensington and the graveyard disappeared, but many of Wing’s papers, like the sheet with the Wing nut design, still survive in their archives.

My thanks to Melssa Dehner and Ben Gross for their help with this post.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.