Scientist of the Day - Nikolay Przhevalsky

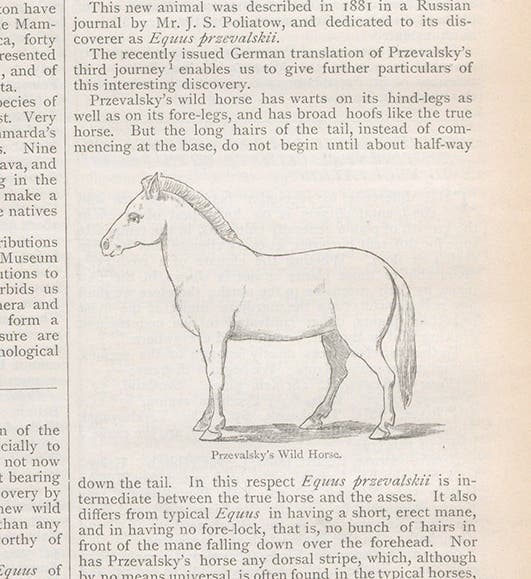

Nikolay Mikhaylovich Przhevalsky, a Russian explorer, was born Apr. 12, 1839. Between 1870 and 1885, Przhevalsky (pronounced Purr-zhe-VAL-ski) led four expeditions into unexplored regions of Central Asia, inhabited, although barely, by Mongols, Dungans, and Chinese. Some of these trips were over 3000 miles in length, through deserts completely devoid of living things, although where he did encounter animals and plants, he collected them diligently, even eagerly, since he was an avid hunter of large game. He found and brought back hundreds of new species of plants and animals, but by far the most famous is the horse named after him, Equus przhevalskii, Przhevalsky's horse, the only truly wild horse in the world. This small, shaggy, fiercely independent beast was so elusive that in spite of repeated attempts, neither he nor his men were ever able to catch one, or even shoot one, so the specimen skin and skull he brought back was one obtained as a gift from a Mongol. The Mongols called them takhi. Przhevalsky supposedly pictured the horse in the travel account of his third expedition, but we do not have any of Przhevalsky’s narratives in our library, so we make do with the first published image in a journal, published in Nature in 1884 (first image).

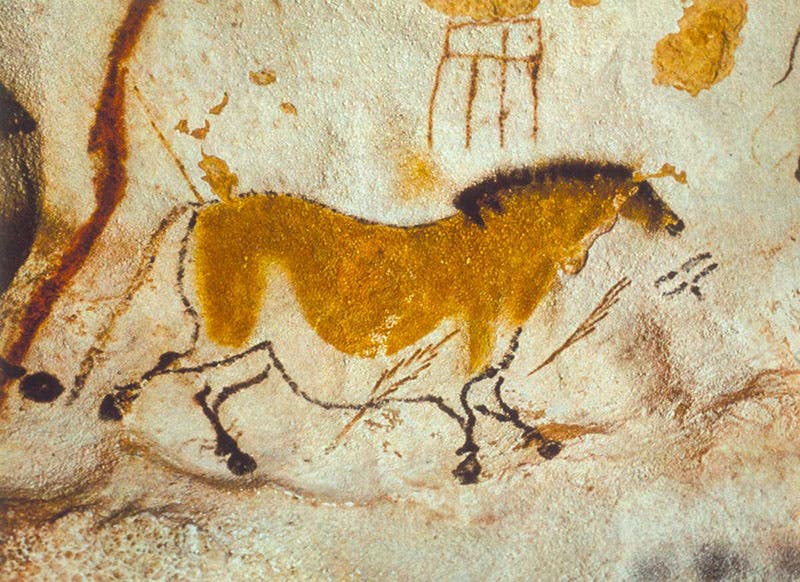

Przhevalsky's horse was probably the very species drawn by Paleolithic artists on the walls of the caves in the Dordogne region of France, such as the one at Lascaux (fourth image). Whether it is truly wild is currently up for debate – there have been some DNA-based studies recently that claim that Przhevalsky's horse is descended from a breed domesticated by the Botai culture in the fifth millennium B.C.E. The evidence is however contested by others. We prefer to believe, for now, that the takhi are a breed untouched by humans until quite recently. And in this case, the human touch was a good thing. Przhevalsky's horse disappeared from the steppes in the last century – the last wild animal was seen in 1969. Were it not for a dozen captured specimens that were preserved and bred in zoos around the world in the early 20th century, the species would have disappeared. By the 1990s, there was a large enough stock built up in the West that they could be reintroduced into Mongolia, where they have slowly taken hold in national parks and nature preserves. The last estimate I saw (2016) put their numbers at about 2000 in the wild, and it is believed that the genetic diversity is great enough that the breed is in good shape and will continue to prosper. We hope so.

Nikolay's goal on each expedition was to reach Lhasa in Tibet and meet the legendary Dalai Lama. He was never successful in this, although by all other criteria, his expeditions were truly epochal. He became a nationally known figure in Russia and was lionized by many as the archetypal explorer, the greatest Russian adventurer ever. This is somewhat surprising, for by most human standards, Nikolay was not a very likeable man; he killed with abandon, despised all races except the Russian, and abhorred most of the conventions of human society. He was very much like his horse, fierce, antagonistic, and intolerant of others.

Nevertheless, he continues to be a revered figure, perhaps aided by the fact that he died relatively young, at age 49. He died in Karakol in Kyrgyzstan of typhus in 1889, as he was about to set out on his fifth expedition (for many years after his death, Karakol was known as Przhevalsk, in honor of the explorer). There is a monument there, and another in Alexander’s Garden in Saint Petersburg.

There was an excellent article in Smithsonian Magazine in 2016, about the reintroduction and current state of the Przhevalsky horse population in Mongolia, supplemented with beautiful photographs of takhi in the wild by Sean Gallagher; we include one of those here (fifth image). You may read the entire article, and see the rest of the photographs, online.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.