Scientist of the Day - Oliver Lodge

Oliver Joseph Lodge, a British physicist, was born June 12, 1851, in Staffordshire, home of the English potteries. His father sold clay to the potters, and Lodge worked in that business until he was in his early twenties, but he also managed to get a good education at the University of London, becoming quite interested in physics, especially electricity and magnetism. When James Clerk Maxwell published A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism in 1873, Lodge obtained a copy and pored over it for years, even though he didn't really have the mathematical training to deal with it properly. But he took note of Maxwell's conclusion that light is an electromagnetic wave, and that it ought to be possible to generate other such waves, with longer wavelengths that the eye could not observe. Lodge would work on this for the next 20 years. He got to know the Irishman George Francis Fitzgerald, and Oliver Heaviside, and all were devotees of Maxwell, so much so that they have been referred to, by modern historians, as "the Maxwellians."

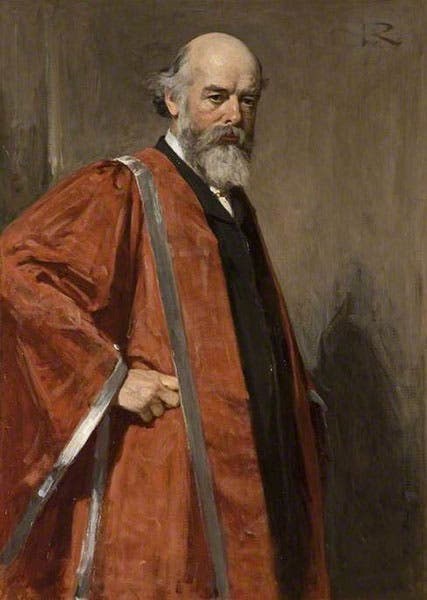

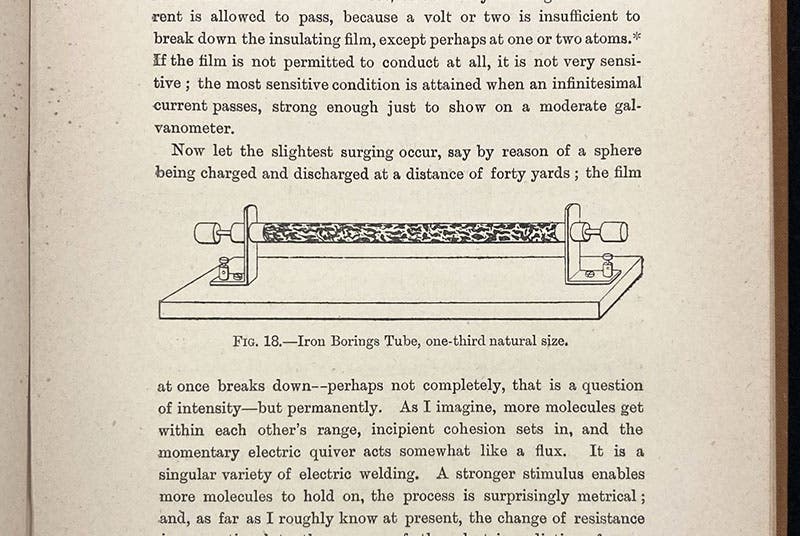

It was on a train trip in 1889 that Lodge read a journal article and learned that Heinrich Hertz, in Germany, had succeeded in generating and detecting electromagnetic waves with much longer wavelengths than light, on the order of a few feet. Lodge decided to see if he could come up with a better detector. He found one in an invention of Edouard Branly, which Lodge improved and called a “coherer." The most common version consisted of a glass tube filled with iron filings and with electrodes at each end. In the presence of an electromagnetic wave, the particles would "cohere," or stick together, greatly lowering the resistance, and allowing a much larger current to flow, which could then trigger a further detector, such as a mirror galvanometer. With his coherers, Lodge was able to give public demonstrations and, in a sense, make electromagnetic waves visible. The most famous of these was an 1894 lecture, which was a memorial lecture for Hertz, who had just died. Hertz was unknown to most people outside the Maxwellian circle, but after Lodge, he was unknown no more. Just a year later, Guglielmo Marconi got into the wireless business (and into a priority tussle with Lodge). Lodge published his lecture, with some additional material, in 1894, and we have a second edition (1897), from which we reproduce here the title page and a wood engraving of an iron-filing coherer (third and fourth images).

Some of the instruments Lodge used in his 1894 lecture, including two coherers, are in the Science Museum, London, along with over 30 other instruments, mostly coherers, from Lodge’s collection. I do not know if any are on display. We show one of them, the 1894 iron-filing coherer, as our first image.

Lodge became a prolific writer of science books for the general public. He had already published his Modern Views of Electricity in 1889 before he became a public advocate of Hertz. His little book containing his Hertz lecture went through many printings. We have some 42 books in our Library that come up when you search for Lodge as author, many of them later printings, but still, that is a lot. He even attempted to do history of science, as with his Pioneers of Science (1893) which began with Copernicus and included discussions of Galileo, Newton, William Herschel, and the discovery of Neptune. It is not great history, but it is not terrible, either. He recognized the genius of Kepler, which not everyone did in 1893.

An interesting feature of Lodge's work in electromagnetism is that he required an ether to make it work – that is, he needed something for the waves to "wave in." The ether began to disappear from electromagnetism after the failure of the Michelson-Morley experiment in 1887 to detect such an ether, and especially after Einstein showed it was unnecessary (see our post on Morley, and our post on Fitzgerald). But Lodge, as far as I can tell, never gave up the ether, which put him seriously behind the times by the 1920s.

Lodge was also, like Alfred Russel Wallace, an ardent spiritualist, believing that the dead could communicate with the living. Lodge lost a son, Raymond, in the First World War, and he believed that a medium had connected him with his dead son. He wrote and published a book on the experience, which attracted a great deal of attention, both negative and positive.

Still, Lodge was one of the best-known physicists of late Victorian England, and he was duly caricatured by Leslie Ward in Vanity Fair in 1904 (fifth image). He taught at both Liverpool and Birmingham – we show you the blue plaque in Birmingham (sixth image). Historian of physics Bruce Hunt, who coined the term “The Maxwellians” in his book of that title in 1994 (seventh image), recognized Fitzgerald as the best of the Maxwellians, but he gave a great deal of credit to Lodge for keeping Maxwell alive while the world waited for Hertz, and then making Hertz’s discoveries known in England. As to who really invented radio, that topic awaits us when we take up Marconi.

Lodge died Aug. 22, 1940, at the age of 89, and is buried in St. Michael’s Churchyard, Wilsford cum Lake, Wiltshire.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.