Scientist of the Day - Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel

Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel, an American astronomer and popular lecturer, was born July 20 (or July 28, Aug. 18, or Aug. 28), in 1808 (or 1809, or 1810), in Morganfield, Kentucky (that is agreed on), to a poor family. His father died when he was two, but he was apparently a very smart kid, and was educated in two schools founded and run by his much older brother in southern Ohio. Mitchel managed to get an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where he received an engineering education. He taught there for several years, then moved to Cincinnati, where he eventually joined the faculty of Cincinnati College, teaching math, engineering, and astronomy. He also gave public lectures on astronomy, which proved to be quite popular, as Mitchel was apparently a very dynamic lecturer. After amassing a considerable following, he decided that Cincinnati needed an observatory and a respectable telescope, so he personally sold shares, 300 of them at $25 each, a considerable sum in those days. With the $7500 thus garnered, he headed for Europe in 1842 to buy a telescope.

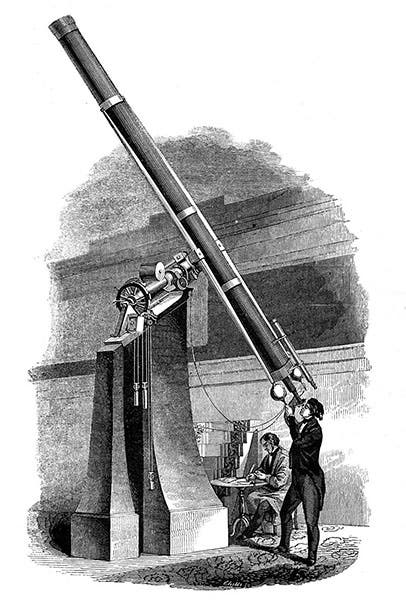

In Munich, Mitchel found an 11-inch lens being offered by the firm of Merz and Mahler, and so he ordered a telescope and mount, outspending his budget by a considerable amount. The telescope was delivered, after a lengthy voyage, in 1845, and installed (third image). Former President John Quincy Adams came to speak at the opening, and the hill on which the observatory stood was renamed Mt. Adams in his honor. The instrument was, for the next two years, the largest telescope in the U.S., until Harvard installed a slightly bigger one. The Cincinnati Observatory, built to house the new instrument, was the first professional observatory in the country, and it would remain an important center for American astronomy for quite some time. It eventually moved out of the center of the city and shifted its focus to become a historical observatory, but it is still there, active and open to the public, and so is Mitchel’s telescope, lovingly maintained, as we see in our first image.

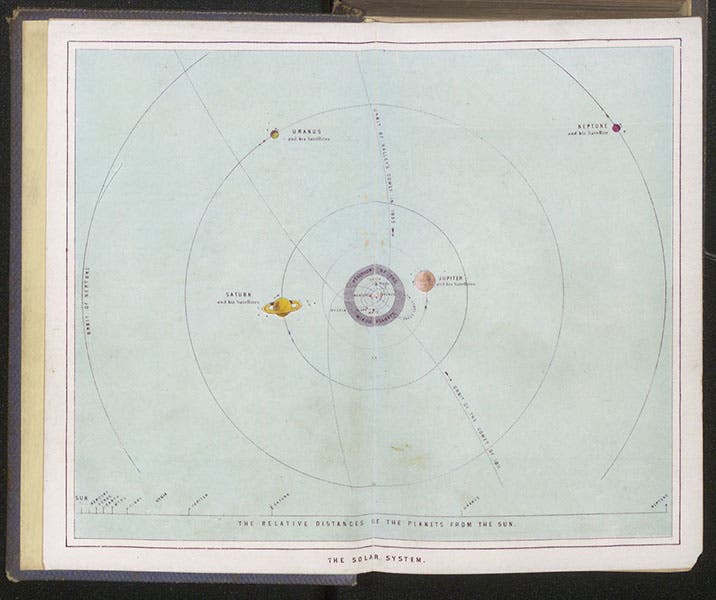

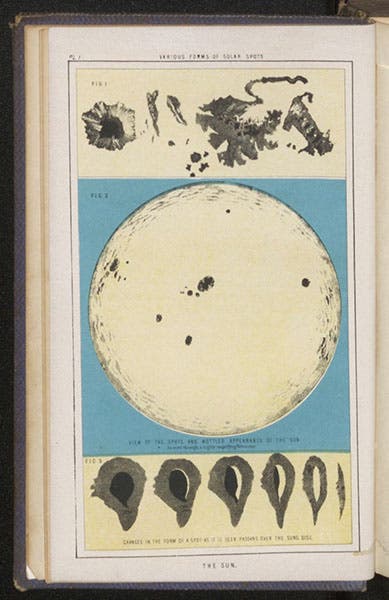

As it happened, Mitchel lost his college lectureship just before the telescope arrived (Cincinnati College burned to the ground), and so he had to find a new source of income. He decided to give astronomical lectures for a living, and he became enormously successful at that, giving talks all through the eastern United States. In 1848, he published a version of his lectures as The Planetary and Stellar Worlds. The book was immensely popular; it was published in England as the Orbs of Heaven (1851) and then went through many subsequent editions in both countries. We have an 1854 edition of the Orbs of Heaven and an 1861 edition of Planetary and Stellar Worlds in our Library. Our post is illustrated with images from the 1861 work, which is about as handsome a work of popular astronomy as one can find from that period. Not only were most of the plates printed in color, which was unusual for the time, but the information they contained was very much up-to-date.

The plate of the solar system that serves as the books’ frontispiece is just beautiful, by far the finest such diagram in any of the many Victorian-era works on popular astronomy in our Library. There are full-page colored plates that show the Moon (with insets of craters), the Sun (with insets of sunspots; sixth image), the relative sizes of the planets, a variety of historical comets, a selection of nebulae, and a beautiful landscape bathed by the zodiacal light (seventh image). Even the binding is lovely, with a gold-blocked cover displaying the Cincinnati refractor (eighth image)

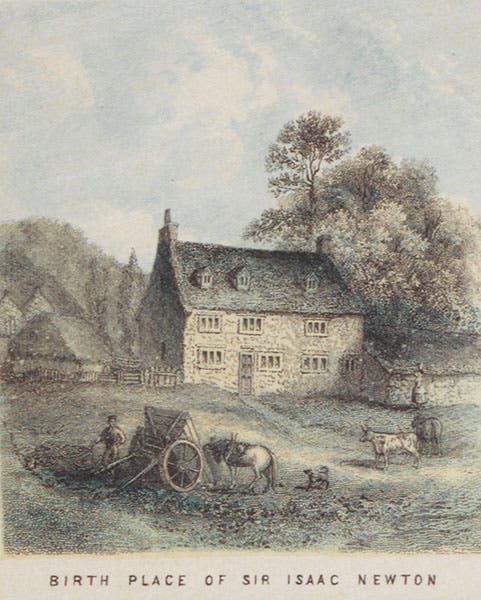

Mitchel had a great interest in the history of astronomy – the first half of the book is a historical review – and while he does not include portraits of his favorite astronomers, he does illustrate two locations of historical interest: Newton’s birthplace in Woolsthorpe (ninth image), and the original Greenwich Observatory.

It must be said that Mitchel probably didn’t have much of a hand in the production of the 1861 edition of his book, since by that time he was a General in the Union Army and conspiring to steal a Confederate train, an enterprise that failed but became known as the Great Locomotive Chase and inspired several films. His military career did not last long, as he died of yellow fever in 1862.

There are many portraits surviving of General Mitchel, but only a few that show the astronomer; we drew our second image from a pre-war carte de visite. Mitchel was buried in Green-wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, where, within 10 years, he would be joined by Elias Howe, Louis Moreau Gottschalk, Samuel F.B. Morse, and George Catlin. His gravestone, with what one might think would be the definite birth and death dates, may still be seen (tenth image). The memorial stone also suggests an explanation as to why the spelling of Mitchel’s last name changed from Mitchell (the name on all his books) to Mitchel, the form now used: there clearly was no room for a second “l” on the tombstone.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.