Scientist of the Day - Otto Lilienthal

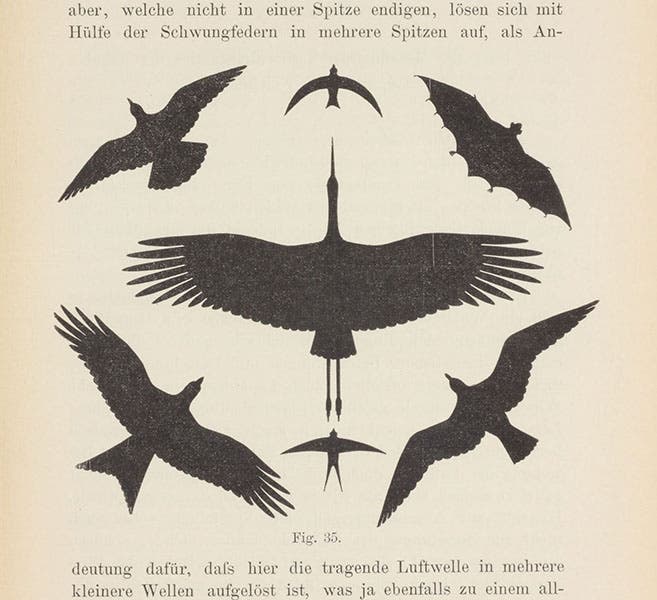

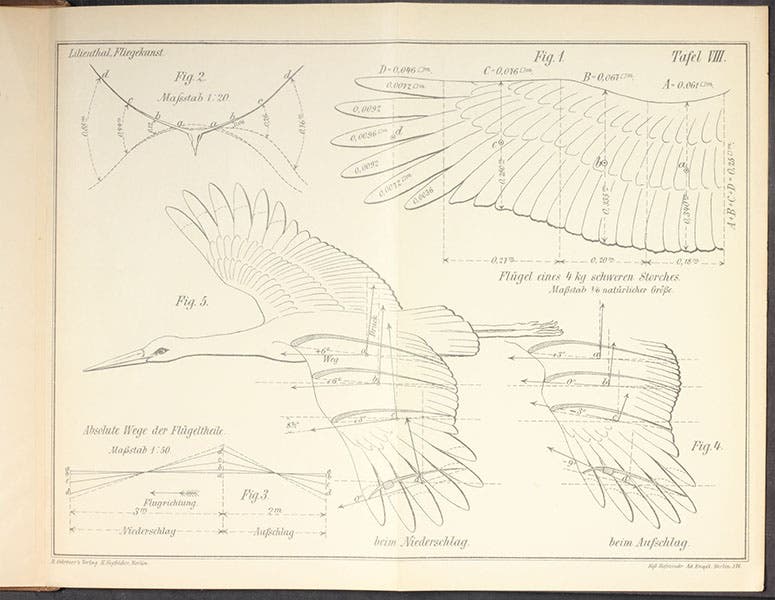

Otto Lilienthal, a German engineer, was born May 23, 1848. Lilienthal was one of the most notable pioneers of human flight in heavier-than-air craft. Before he made any attempt at human flight, he studied birds, for he was convinced that the first human-made aircraft would resemble birds and use the principles of avian flight. In 1889, Lilienthal published the fruits of his studies, Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst (Bird Flight as the Basis of Aviation). We have a copy in our Library. The value of the book to later aviators such as the Wright brothers lay in the data provided by Lilienthal about such things as the proper shape of wings and the optimum angle of attack to generate the most lift. But there are several memorable images to appeal to us non-aviators, such as a mosaic of bird silhouettes that show seven different but successful ways of mastering the air (second image). There is also a plate at the end that breaks down the structure of a bird's wing in great detail, feather by feather (third image).

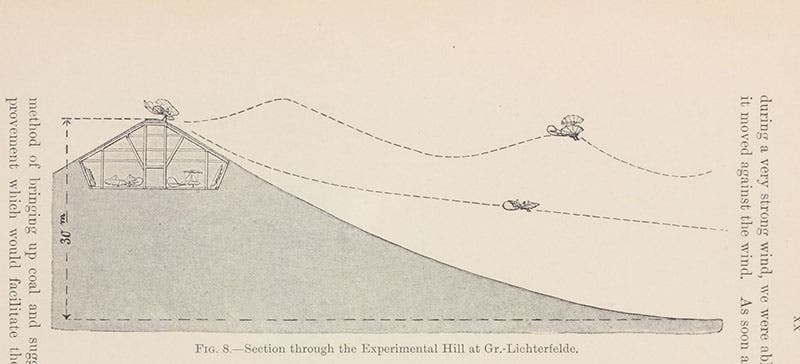

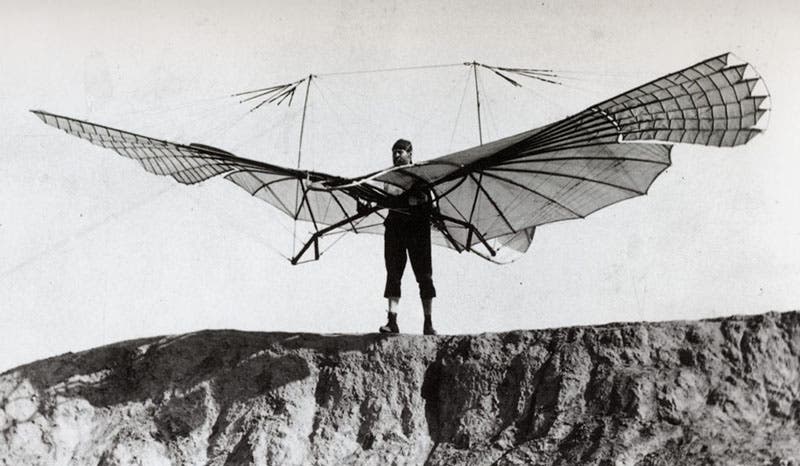

Soon after the publication of his book, Lilienthal began building and flying his own gliders. True to his principles, they all look like birds and are supported by bird-like wings, although sometimes in an arrangement – such as a biplane – never mastered by birds. For a take-off ramp, Lilienthal built an artificial hill in a suburb of Berlin, courtesy of a canal-digging company which gave Lilienthal their extracted dirt. He even placed a yurt-shaped hangar at the top. When Lilienthal's book was republished in 1910, his younger brother Gustaf contributed a new introduction and included quite a few photographs of Lilienthal gliding, as well as a cutaway view of Fliegeberg (Flight-hill, the name Otto gave to his launch pad). We have a 1911 English translation of the 2nd edition, which includes all the photographs and diagrams, and we show you the text illustration of Fliegeberg (fourth image). The hill is often described as 50 feet tall, but as you can see from the drawing, it was 30 meters, or 98 feet, from top to bottom.

Lilienthal built 16 different gliders over the course of six years, with his favorite being number 11, because it was so stable and reliable. They were nearly all hang gliders, with the pilot suspended beneath the wing. Lilienthal controlled his gliders by swinging his body – there were no ailerons or elevators on the wings or tail. He did experiment with moveable wing tips, which birds have, but he was really saving those for his first powered craft.

Lilienthal became quite well known and his flights always attracted sizable crowds. The website wright-brothers.org has four photographs of Lilienthal in flight. The site does not give any credit for the photographs, but they look authentic enough, and are of excellent quality. We show one that captured Lilienthal at the top of his launch-hill,� about to take off (fifth image). The Library of Congress also has an original photographic print from 1895, which is well documented, and which shows Lilienthal in flight. We include that here as well (first image).

Lilienthal planned to power his aircraft eventually, and he constructed engines for powered flight. But mostly, he concentrated on mastering design and flight technique. He got better and better at controlling his craft, and the designs improved in terms of lift and stability; by 1896, he was making glides of nearly 800 feet.

Unfortunately, Lilienthal found no way to get around the law of gravity. On Aug 9, 1896, as he was flying good-old no. 11, he ran into an uplift, the aircraft stalled and plummeted 50 feet to the ground, and Lilienthal broke his back. He died the next day. Three years later, his principal European competitor, and in some ways his disciple, Percy Pilcher, fell from his glider and died. With the loss of these two men, Europe was suddenly bereft of experienced aviators, and the baton of manned flight was passed to America, to individuals such as Octave Chanute, Samuel P. Langley, and the Wright brothers. All of them admired Lilienthal as the one who made their own successes possible, and all were deeply grieved by his death.

The National Air and Space Museum has a restored Lilienthal glider on display, hanging from the ceiling – a true hang-glider – with a waxen Lilienthal at the controls (sixth image). It makes an impressive display, along with nearly everything else hanging from the NASM ceiling. If you have never visited the Museum, and you have any interest at all in the history of aviation, it is an absolute must-see on your next trip to Washington, DC.

There are surprisingly few portraits of Lilienthal, and no really good ones. The one most often reproduced was used as a frontispiece for the 1911 translation of his bird flight book; we use it here as our last image.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.