Scientist of the Day - Pei Wenzhong

Pei Wenzhong, a Chinese paleontologist and anthropologist, died Sep. 18, 1982, at age 78. Pei is one of several "fathers of Chinese anthropology," honored because of the role he played in the discovery of "Peking Man," more properly known then as Sinanthropus, and referred to now as Homo erectus. Pei (referenced in the older literature as W.C. Pei) was only 24 years old when he joined the Cenozoic Research Laboratory in Peking, as Beijing was then called. The Laboratory had been established with a Rockefeller Foundation. grant, and therefore had an American as "honorary" director, the anthropologist Davidson Black. It was founded because of various teeth that had been discovered around Peking that seemed to be of early human origin. One especially promising site was called Chou Kou Tien (now Zhoukoudian), an amalgam of sediments and fossils about 25 miles southwest of central Peking. It contained an abundance of Pleistocene mammal fossils and a few fragments of human-like fossils. Wenzhong was assigned to the Chou Kou Tien excavation team (second image).

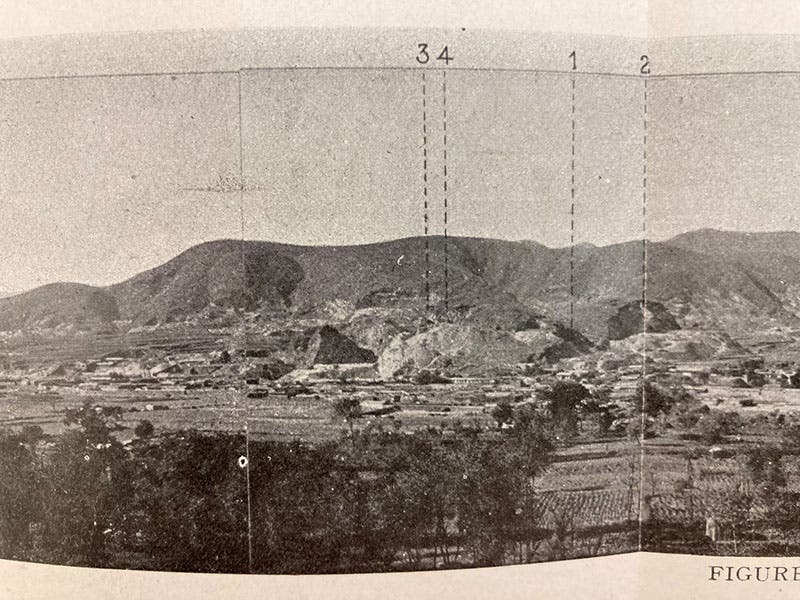

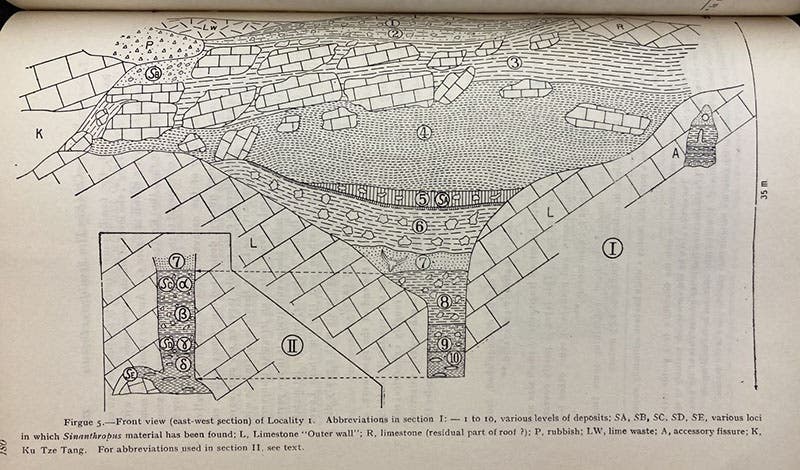

It was on the night of Dec. 2, 1929, that Pei made his big discovery. As we see from a contemporary photograph of the entire area of Chou Kou Tien (third image) and a stratigraphic diagram of what was called Locality 1 (fourth image), where Pei was working, there was a cone-like depression in the bedrock, that had been filled over eons of time with sediment and fossils. Weng and the rest of the team had dug all the way down to the bottom of the cone, which was nearly inaccessible because of the narrowness of the space. Just before they were about to wrap up excavation for the year, Pei found his way to the very bottom and discovered a tiny cave, partially open, off to the left in the diagram. The diagram has an inset at the far left that shows the tiny cave, which is labelled “SE.” In it, working by candlelight, Pei found a round protrusion that he guessed was a skull cap. Further investigation showed that to be the case. He was tempted to leave it until the next day, when they could see better, but not surprisingly, finally elected to excavate it that night. It was indeed a primitive human skullcap, partially encased in a matrix of travertine.

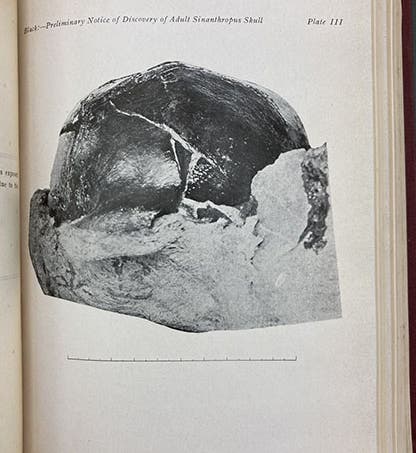

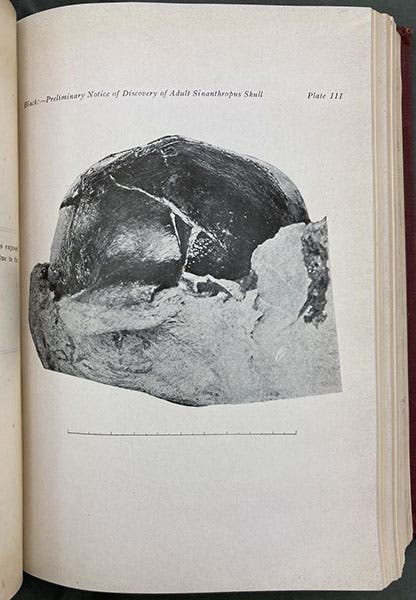

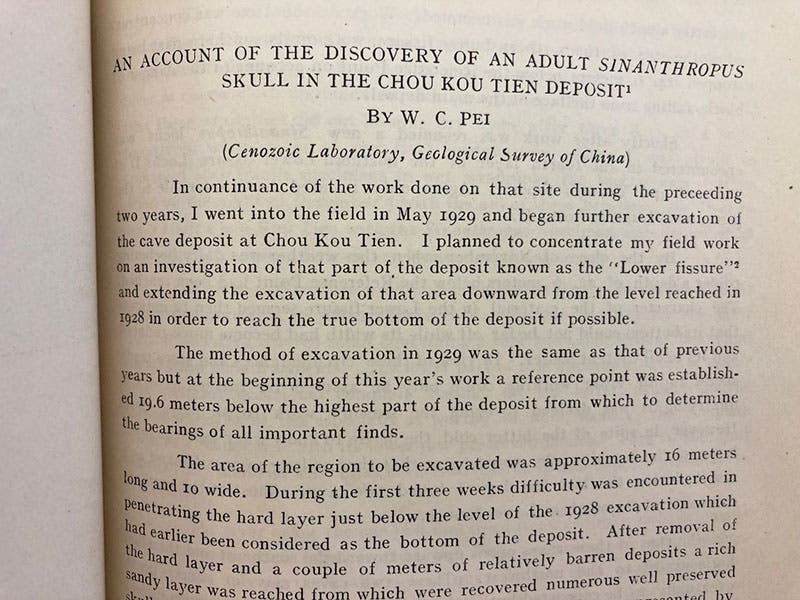

After getting it back to his field quarters, Pei tried to prepare it for shipment to his boss, Davidson Black, back in Peking. He wrapped it in cotton, then burlap soaked in plaster, in the now conventional manner. The only problem was that it was so cold that the plaster would not dry. Finally, after waiting two days in vain for the plaster to harden, he set up three charcoal braziers and warmed the wrapped fossil until it was hard and safe for travel. He had to smuggle it by the guards that manned the railway, but on Dec. 6, he managed to present it to Black in person. Black was ecstatic – here was the evidence they had sought for so long, ever since the first tooth had turned up in 1921. Before the end of the year, they organized a symposium and presented the skull to the public. And by January 1930, papers were published in the Bulletin of the Geological Society of China that described the site and the fossil, and provided photographs of both. We have a complete run of that journal in our serials collections, and issue 3 of volume 8 is the source for four of our images today.

Diagram of the deposits at Locality 1 at Chou Kou Tien; Pei found the Sinanthropus skull at the very bottom of heap of deposits at bottom center, in a tiny cave, shown in an inset at left and marked “SE”, from a paper by Pierre Teihard du Chardin and G.C. Young in Bulletin of the Geological Society of China, vol. 8, 1929 (Linda Hall Library

Davidson Black wrote the most detailed article in the Bulletin, and we discussed it, and showed some of the photographs, in a post on Black that we wrote just last year. But Pei, as the discoverer, was invited to contribute a paper of his own, describing not the fossil, but the manner of its discovery. We show here the beginning of Pei's paper (fifth image), and a different photograph of the skull than the one we showed in our post on Black (first image). The caption describes it as partially removed from its "field wrappings". Those were the burlaps wrappings applied by Pei at Chou Kou Tien.

Pei later became the leader of the Chou Kou Tien excavation program, before leaving to get his PhD in Paris. He returned to the Cenozoic Research Laboratory and was there in 1941 when the threat of war was looming. Pei arranged for all the Sinanthropus fossils in the vault to be replicated, and had the originals carefully packed and loaded into two large crates, with the intention of shipping them to the United States for the duration of the war. Unfortunately, at just this time, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and in all the tumult, the crates were lost track of and disappeared. They have never been found, although not for lack of trying. Fortunately for Sinanthropus, excavations resumed at Chou Kou Tien after the war, and many more specimens were unearthed, including some skulls that were more complete than the first. So Sinanthropus (now Home erectus) studies have carried on. But the original skuill found by Pei that night of Dec. 2, 1929, has never turned up, and is probably lost forever.

There are not many photographs of the younger Pei. A group photo session was held at Chou Kou Tien in 1928; we show one photo from that session here (second image), and included a slightly different one in our post on Black. Pei is at the far left in both cases. There are more photos of the “venerable” Pei Wenzhong, one of which we include here (sixth image)

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.