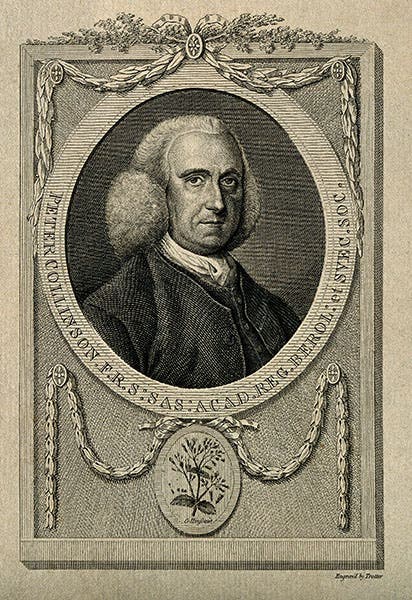

Scientist of the Day - Peter Collinson

Peter Collinson, an English cloth merchant and gardener, and a Quaker, died Aug. 11, 1768, at age 74. Collinson is hardly known to the general public, but he played a major role in facilitating the work of others who did become famous. Young Ben Franklin sent Collinson his first papers on electricity, and Collinson had them published by the Royal Society, and he encouraged Franklin to pursue further electrical investigations. Collinson supported the travels of John Bartram in the American colonies, and received in exchange hundreds of packets of seeds, which he distributed to gardeners all over England. Occasionally the traffic went the other way; Collinson sent Bartram some Siberian rhubarb that he had raised; Bartram successfully replanted it, and this was the source for much of the rhubarb that you buy today at the city market.

That Collinson was a Quaker was not incidental to his influence. Many Quakers were at the hub of support networks in the 18th century, providing funds and encouragement to a variety of collectors, especially botanists, since many well-to-do Quakers had ornamental gardens of their own. See our post on John Fothergill, another Quaker benefactor, who took young William Bartram under his wing.

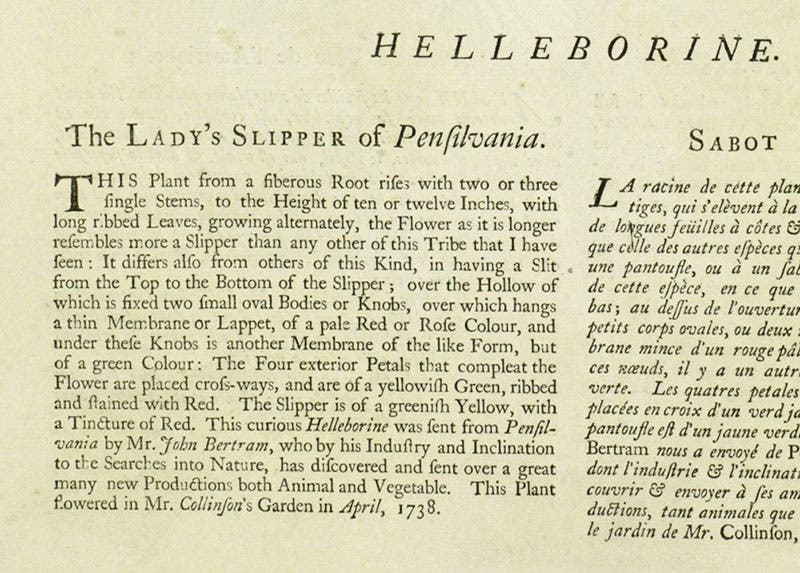

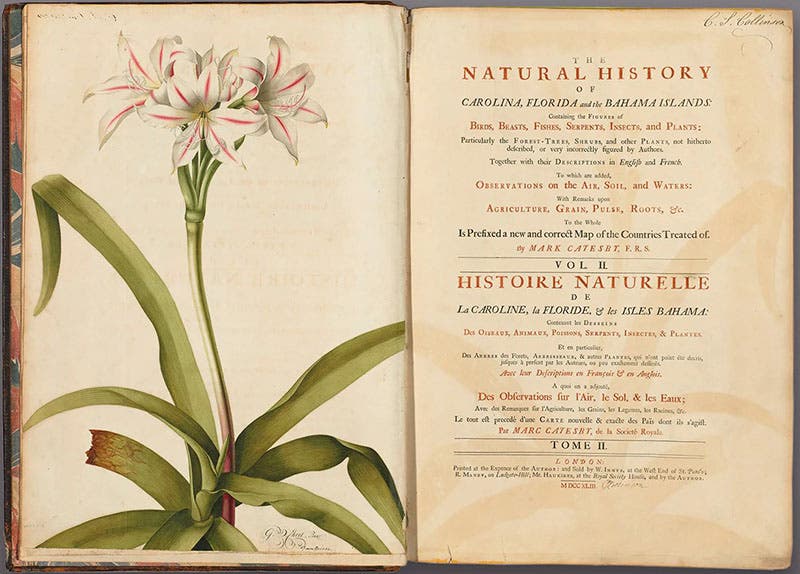

Collinson was a principal patron of Mark Catesby, who was studying the flora and fauna of the southern colonies, and Collinson lent Catesby the money to publish his Natural History of Carolina (1731-43) [1729-47], a second edition of which we have, and displayed in The Grandeur of Life exhibition in 2009. As an example of how interconnected these far-flung naturalists were, John Bartram sent Collinson a specimen of a Pennsylvania plant, the lady’s slipper, which Collinson planted in his garden and brought to flower. Catesby, who had already published volume 1 of his Natural History (thanks to Collinson), saw the flower in Collinson’s garden in 1738, drew it, and then published it in volume 2 of his Natural History. In fact, since there were two varieties, both growing in Collinson’s garden, he published it twice, with one plant blooming in front of a black squirrel (first image), and the other hiding behind a wonderful American bullfrog (third image). We also include below a detail of the accompanying text for the latter plate, where Catesby mentions that he saw the Iady’s slipper growing in Collinson’s garden (fourth image).

Collinson wrote thousands of letters during his lifetime, passing along information, describing plants coaxed into bloom in his garden, asking for seeds or seedlings, mollifying rival patrons, advising collectors, sometimes including offprints from the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal society, sometimes explaining a shipment of “things,” as when he sent a glass electrical tube to Philadelphia in 1747, where it ended up in the hands of Franklin, thus beginning their interaction and exchanges. More than 750 of these letters survive, and a third of them were published with notes and illustrations as "Forget not Mee & My Garden... Selected Letters 1725-1768 of Peter Collinson, F.R.S., ed. by Alan W. Armstrong (2002). The letters are fascinating reading, especially when you are reminded that Collinson wrote most of them while working at his mercer's shop (he mentioned in one of his letters to Franklin that it was being written "behind the counter."

Collinson was given a special set of the Natural History of Carolina by Catesby, as a way of repaying his patron. It is what we call extra-illustrated, with additional watercolors by Catesby, George Ehret, William Bartram, and other artists indebted to Collinson. It passed to Collinson's son, and eventually ended up, along with a Collinson commonplace book, in the library of Edward Stanley, the 13th Earl of Derby, who had quite a collection of curiosities and books in the family estate at Knowsley Hall near Liverpool. And it stayed with the Stanleys for many generations. But in 2022, it was sold by the 19th Earl to the Arader Galleries in New York, which is offering it for sale, along with the commonplace book. Their description may be found here; the image just above is from their website. This is a unique piece of Collinsoniana; I hope it ends up in a library where scholars have access. It would seemingly qualify as a British national treasure; why authorities allowed it to leave the country, I cannot say.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.