Scientist of the Day - Peter Forsskål

Peter Forsskål, a Finnish naturalist and explorer, was born Jan. 11, 1732. Because Finland was then part of the kingdom of Sweden, Forsskål was often referred to as a Swedish scientist, but no more. He studied for some years at Uppsala University near Stockholm; his initial interest was in Middle Eastern languages as well as philosophy, but he also fell under the spell of Carl von Linné, better known as Linnaeus, who was then at the height of his fame at Uppsala, and Forsskål became quite an accomplished botanist himself. He studied for a few more years at Göttingen University, where he continued his pursuit of knowledge of the ancient Near East, and thus attracted the attention of Johann David Michaelis, an orientalist who thought that we could better understand Biblical history if we went to some of the isolated regions of the Middle East and studied their languages and culture. It was Michaelis who apparently convinced King Frederick V of Denmark to sponsor a scientific expedition to the southern Arabian peninsula, to what then was called "Arabia Felix," and which now comprises the country of Yemen. This was one of the very first scientific expeditions to Egypt and Saudi Arabia, departing some 37 years before Napoleon launched his more famous scientific expedition to Egypt in 1798. The Danish Arabia expedition, as it is usually called, was on a much smaller scale than Napoleon's venture, since it was comprised of just 6 scholars, and there was no army to protect them. They would be very much on their own.

A batfish or spadefish, presumably drawn by Peter Forsskål and published by Carsten Niebuhr in Icones rerum naturalium, 1775, BEIC digital library (gutenberg.beic.it)

Forsskål was one of the six members of Frederick V's scholarly invasion of Arabia Felix. He was the botanist/zoologist, and since he was appointed in 1759, and the expedition did not leave until early in 1761, he had over a year for the great Linnaeus to prepare him for the trip, which Linnaeus happily did. Another member of the expedition was Carsten Niebuhr, a mathematician, astronomer, and cartographer. They departed on Jan. 4, 1761, on a Danish naval vessel, and went first to Alexandria, where Forsskål collected Egyptian plants and animals that were unknown to northern European naturalists. After a year in Egypt, they headed for the southern coast of the Arabian peninsula, where Forsskål collected more specimens, most of them again new to European scientists. Unfortunately, the diseases of the area were also new to the Scandinavians, and they began to succumb to malaria, one by one. The philologist went first, followed very soon by Forsskål, who died on July 13, 1763, at the age of 31. They were followed in turn by the surgeon and the expedition artist; only Niebuhr survived, which was fortunate for Forsskål, because Niebuhr, much later in 1775-76, published the results of Forsskål's botanical and zoological investigations in three separate volumes, and kept Forsskål from disappearing into the maw that holds brilliant but unpublished scientific figures.

Forsskål is quite a hero in modern-day Sweden and Finland, and there were lavish celebrations of him on the 250th anniversary of the departure of the Danish Arabia expedition (2011) and of Forsskål's death (2013). But the public was not honoring his skill as a naturalist, although that was considerable. They mostly were toasting a short treatise that Forsskål published in 1759, Thoughts on Civil Liberty, where he presented strong arguments for the importance of individual freedom for all the citizens of a country, including freedom of religion, and especially, freedom of the press. The pamphlet, printed in Stockholm, was condemned by the city council, who ordered the entire printing to be confiscated, ending Forsskål's hopes for an academic career in Sweden. But seven years later, after Forsskål’s death, the Swedes were the first to ban censorship of the press, and the publication of Forsskål's work was and is considered to be the event that catalyzed the movement toward freedom of the press in Sweden.

Not surprisingly, there is little in the way of graphic memorabilia of the life of Forsskål. We have one portrait, in a castle in Uppland, Sweden. This portrait was the basis for our other image, a Finnish commemorative postage stamp of 1979: which also shows the title page of his dissertation on civil liberty (fifth image). And there were a number of plants and animals named after Forsskål by contemporaries who survived him; we show a fish, Leiognathus equulus Forsskål, named and drawn by Mungo Park in 1775 (fourth image).

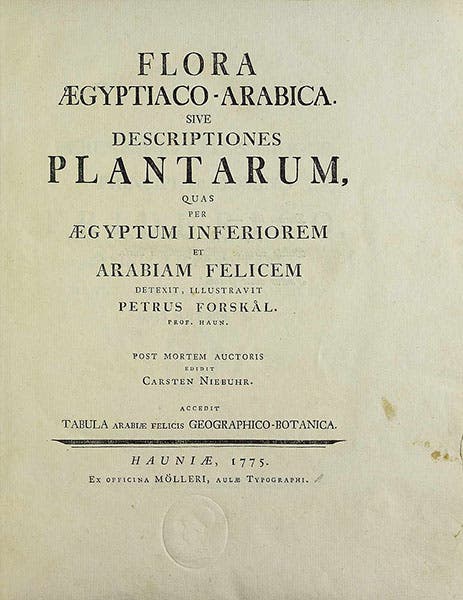

None of the three books that Niebuhr published of the expedition work of Forsskål are in our Library collections; acquiring one or more of these would be a nice way to honor the short scientific life of Peter Forsskål. Until that time comes, we show a plate of some sort of batfish, presumably drawn by Forsskål and included by Niebuhr in Icones rerum naturalium (1775), and the title page of Forsskål’s posthumous Flora Aegyptiaco-Arabica (1775), both taken from online digital copies (second and third images).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.