Scientist of the Day - Peter Higgs

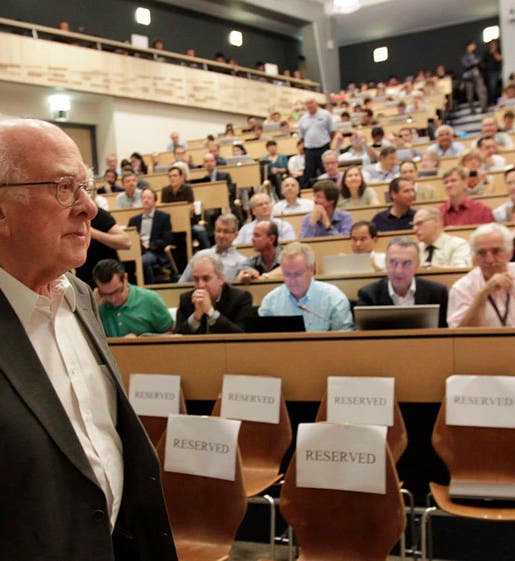

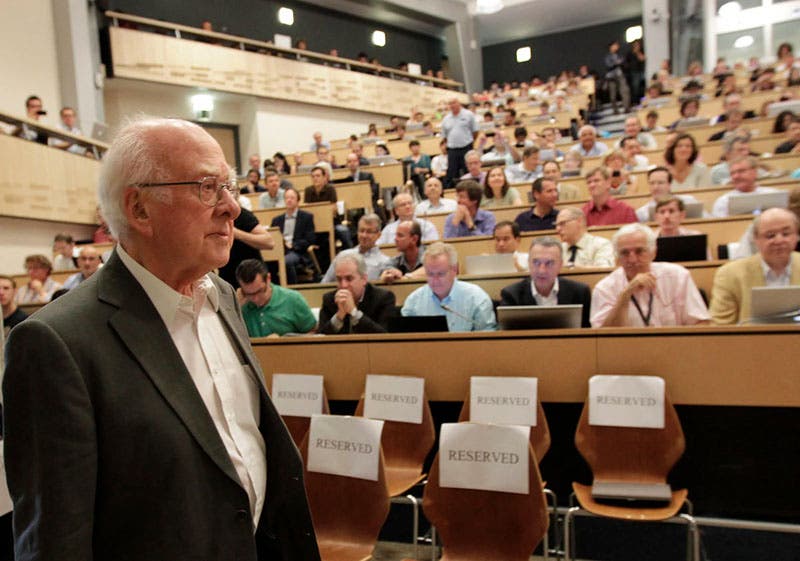

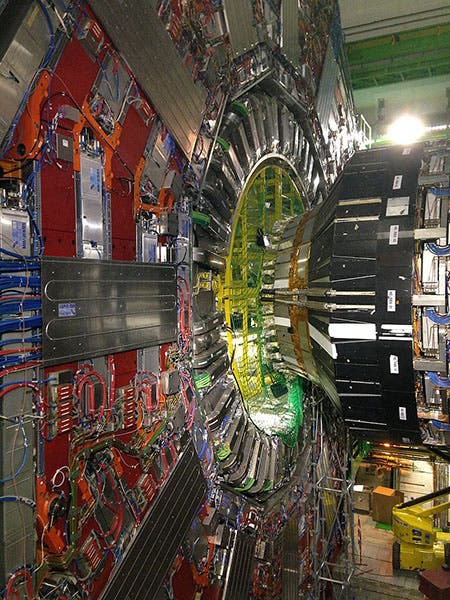

Peter Ware Higgs, a British theoretical physicist, was born May 29, 1929. He studied at University College, London, and, after various teaching positions in Edinburgh and London, ended up at the University of Edinburgh, where he taught and confronted the particle zoo for the rest of his career. In 1964, Higgs (and 5 other physicists in three separate papers) proposed the existence of a field, pervading the entire universe, that is responsible for the fact that particles have mass. That field is now called the Higgs field. It has been referred to as the “cosmic molasses,” an apt term, for as elementary particles attempt to move through it, they acquire mass, a property that cannot otherwise be accounted for. Higgs further suggested that if such a field exists, then under certain circumstances the field should give rise to a massive particle, which is now known as the Higgs boson. Because the "certain circumstances" involve accelerating protons through some trillions of electron volts, it took some time to confirm the existence of the Higgs boson, for it required the building of a massive super-collider capable of accelerating protons to unprecedented high energies. That was finally made possible at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Switzerland, which became operational in 1910 (almost 50 years after Higgs' prediction). Hadrons are particles built up from quarks, and include protons, neutrons, and mesons. In July of 2012, it was announced that a particle with the predicted mass of the Higgs boson had been recorded by two detectors (called ATLAS and CMS), and this was a big deal in the physics community; the success of the search was celebrated worldwide. One year later, Higgs received a share of the Nobel Prize in Physics for 2013.

Most of us who are not particle physicists cannot appreciate the reaction that followed the prediction of the Higgs field and the Higgs boson, and the excitement generated by its confirmation in 2012. But we can consider one other puzzle: why are all these things named after Higgs? He did publish a paper on the subject in 1964. But so did François Englert (who received the other half of the 2013 Nobel Prize) and Robert Brout, two French physicists, and, at the same time, so did an Englishman and two Americans, Tom Kibble, Gerald Guralni, and C.R. Hagen. Three teams, comprised of six men, made identical predictions. Higgs never called his predicted entities the Higgs field and the Higgs boson. He was in fact quite averse to publicity (he turned down a knighthood in 1999) and would have much preferred that the new particle be named the Englert boson or the Kibble boson. He protested quite a few times that scientists other than himself played an important role in predicting the Higgs field and Higgs boson. Probably someone has done a study to trace the first appearance of the terms “Higgs boson” and “Higgs field” in both the popular press and the scientific literature, but I am not aware of it. Of course, in the end, inquiries and protests are useless, for no one really controls these things. No matter who passes what resolution, the Higgs boson is always going to be the Higgs boson.

One thing the Higgs particle is NOT going to be much longer is the “God Particle.” That is what Leon Lederman called it in 1993 in a book with that title, before the Higgs boson had been detected. Lederman asserted that he wanted to call it the “Goddamn Particle” because it was causing so much trouble, but the publisher wouldn’t let him. But the press had a field day making fun of physicists who were deifying their elementary particles, and physicists were furious themselves – many (including Higgs), considering the name sacrilegious. Fortunately, the name seems to be going away – Lederman’s book came out 30 years ago – and, since no one seems to like it, I suspect it will soon be a footnote in physics history.

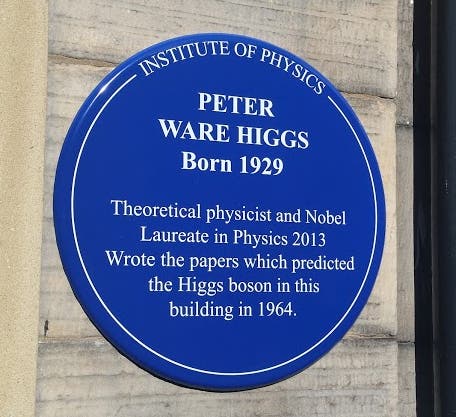

There is a blue plaque honoring Peter Higgs on Roxburgh Street in Edinburgh, outside the building where he predicted the Higgs field and boson in 1964 (fifth image). He died just seven weeks ago, on Apr. 8, 2024, at his home in Edinburgh. Details of his burial have not been made public.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.