Scientist of the Day - Peter Simon Pallas

Peter Simon Pallas, a German naturalist who spent much of his career at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences at the direct invitation of Empress Catherine of Russia, died Sep. 8, 1811, just 2 weeks shy of his 70th birthday. We have published two posts on Pallas, the first showed some images from an English edition of his travels through Russia, and the second discussed his discovery and retrieval of a famous meteorite, the Pallas iron.

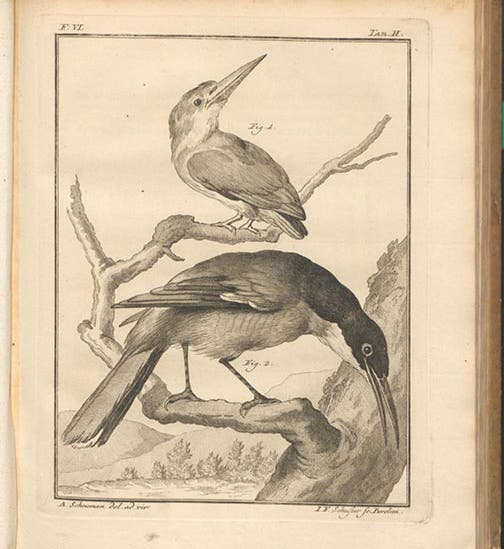

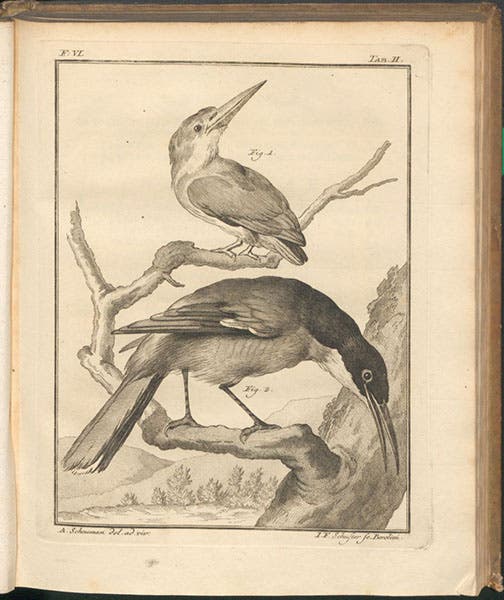

But Pallas was also a gifted naturalist and a dedicated anatomist. In 1767, while he was still in Berlin, Pallas began publishing a work on comparative anatomy that he called Spicilegia zoologica (“Zoological gleanings”). It was issued in 14 fascicles over the course of 13 years. Our copy has the 14 issues bound into four volumes. It is a very handsome set in green-paper-covered boards, made more handsome by the 58 engraved plates scattered within, which we have drawn upon to illustrate today's post.

As the title word “Gleanings” suggests, each fascicle discussed several birds, animals, or invertebrates that had been ignored by, or were unknown to, other naturalists.

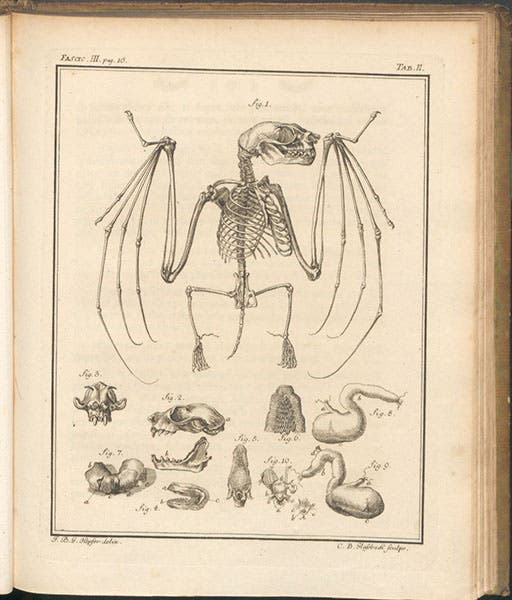

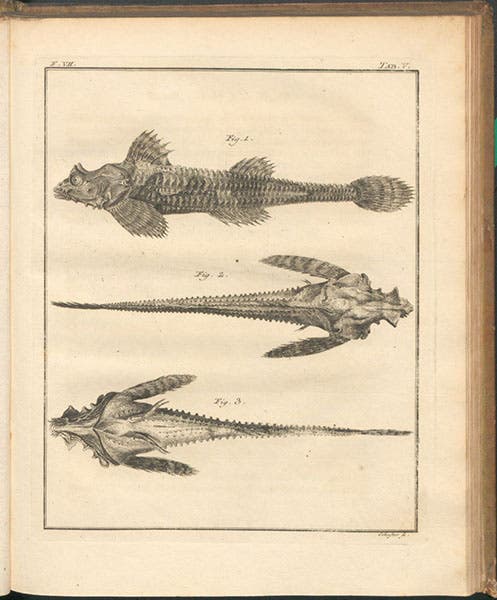

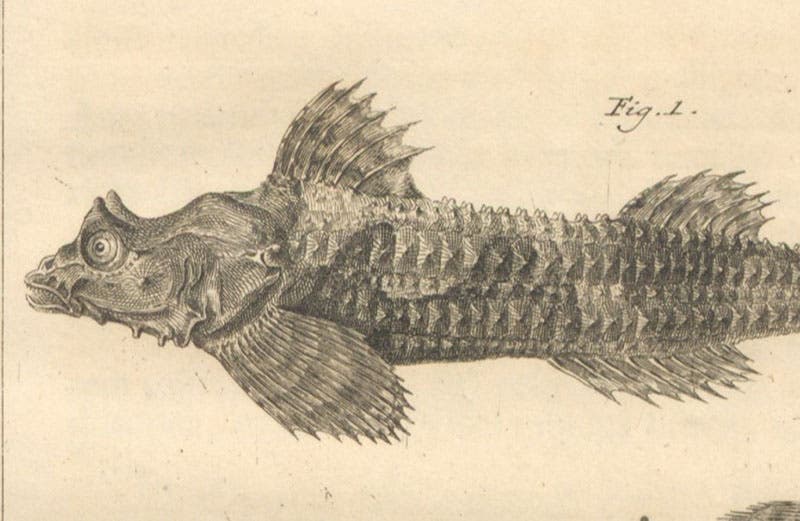

For example, in fascicle 7, Pallas described a fish found in the Sea of Japan that he calls Cottus Iaponicus, and we now call Percis japonica, the dragon poacher. The engraving, which Pallas did not draw himself but commissioned, is excellent, providing 3 different views of this benthic dweller (fifth and sixth images). In other fascicles, we see new species of kingfishers, birds of paradise, and a variety of bats (including one skeleton), goats, and antelopes.

Every new animal was described in depth, including a section for each called “Mensurae,” in which every feature that could be measured was measured, and the results provided in a table. There usually followed a discussion of the animal’s anatomy as revealed by dissection.

Two of the fascicles (9 and 10, 1772 and 1774) treat invertebrates, including zoophytes. Indeed, the main reason I wanted to discuss the Spicilegia is because Pallas, according to a chorus of modern specialists on regeneration in animals, discovered and here announced that planaria can be cut in half, and both halves will regenerate to form whole organisms.

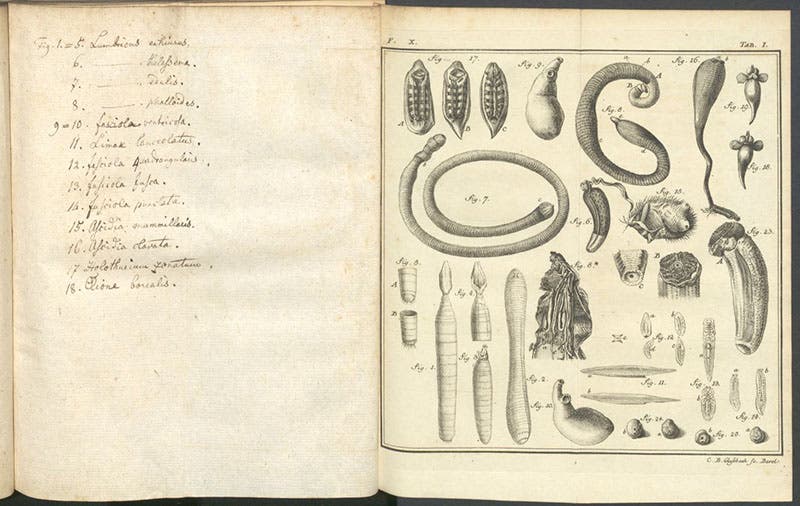

However, when I went looking for Pallas's discussion of planarians, I couldn't find it. So I turned to modern scholarship for help, and discovered that not one of the regeneration biologists who cited Pallas provided a page number; most simply cited the entire 14-fascicle set, suggesting that no one was actually looking at the original source. This is not to say that Pallas did not discover regeneration in planarians, but simply that I do not know where he did so. There are 3 plates of zoophytes in fascicle 10, and while one shows liver flukes and the like (seventh image), I did not see anything that looked like a planarian. So I will need further help from experts before I can solve this conundrum. Fortunately, I know who to ask, since one of the world's experts on regeneration, Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, sits on the library's board of trustees, and I know for a fact that he reads the historic sources he cites. I am sure that with his help, we can resolve the problem, and update this post.

Apparently, a former owner of our set was an invertebrate zoologist himself, for in the two fascicles on invertebrates (and only in those two), he mounted the engravings on spacious stubs and provided captions in ink for each of the figures, as one can see in our last image.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Columbine, hand-colored woodcut, [Gart der Gesundheit], printed by Peter Schoeffer, Mainz, chap. 162, 1485 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/3829b99e-a030-4a36-8bdd-27295454c30c/gart1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)