Scientist of the Day - Philip James de Loutherbourg

Philip James de Loutherbourg, a French painter and designer working in England, was born Oct. 31, 1740. Loutherbourg worked as a set designer in London for some years before turning his talents to large-scale canvases. We include him as a Scientist of the Day because in 1801, he gave us the quintessential painting of the Industrial Revolution, Coalbrookdale by Night (first image). The painting, now in the National Galleries of Scotland, captures, like no other artwork of its time, the changing landscape wrought by the coke-fired blast furnaces churning out iron along the River Severn in Shropshire. It is the very antithesis of the Romantic landscapes that were then starting to become popular. To our mind, the only painting that comes close to capturing the dark side of industrialization is George Wesley Bellows’ Excavation at Night (1908), which is on view in the Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas. By a coincidence that is no coincidence at all, Bellows has also served a short stint as one of our Scientists of the Day, and you may see his take on progress here, where the black hole that would become Penn Station is the first image in the slideshow.

Many of Loutherbourg's other paintings have a maritime theme, such as the Defeat of the Spanish Armada (1796), in the National Maritime Museum, or the Landing at Aboukir Bay (1802), sharing the National Galleries of Scotland with Coalbrookdale by Night. Making a science connection with such paintings might be a bit of a stretch, so we won’t show them here. But one could argue that his Battle of the Nile (1800; second image) in the Tate Britain, records an event of great importance to science, for by destroying the French Mediterranean fleet, Lord Nelson insured that Napoleon's savants would stay in Egypt for two more years and eventually compile for us that blbiliographic wonder, the Description de l'Egypte (1809-1828), which we just happen to have in our collections.

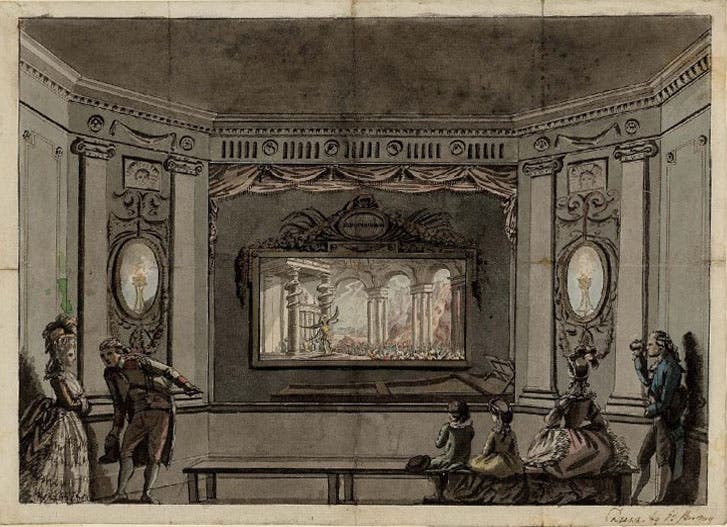

One might further argue that Loutherbourg deserves some acknowledgement as an inventor. In 1781, using his knowledge of stage design, he constructed the Eidophusikon, a small mechanical theater, where strings on pulleys moved cardboard actors, horses, and carriages across the small stage while backdrops and the sky moved in the opposite direction, colored filters produced a play of light from Argand lamps, and mechanical music added to the mystique. The British Museum has an engraving of the original Eidophusikon (third image). It never caught on, but a bevy of 21st-century museum entrepreneurs are now building replicas of Loutherbourg's Eidophusikon for an intrigued public, indicating that perhaps, finally, his time has come.

Loutherbourg painted a self-portrait that is usually used to illustrate articles about him (see Wikipedia, for example), but it shows him as complacent and overly well-fed. We prefer the portrait made by his friend Thomas Gainsborough around 1778, a few years before Loutherbourg dreamed up the Eidophusikon (fourth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.