Scientist of the Day - Pierre Jaquet-Droz

Pierre Jacquet-Droz, a Swiss clockmaker, was born July 28, 1721, in Neuchâtel, now part of Switzerland, but then part of Prussia. Little is known about Pierre, except that he had a son, Henri-Louis, and an adopted son, Jean-Frederic Leschot, and that together, between 1768 and 1774, they constructed three of the most amazing automata ever devised, anywhere, anytime.

The first (in order of discussion – we don't know in what order they were constructed) is a young woman, who sits before a small clavichord, her eyes downcast. When prompted, she places her fingers on the keyboard and plays a melody, just like a human would. Her eyes follow her fingers as they play. She is called the Musician, or the Musicienne. The other two automata look like young boys, perhaps the younger brothers of the Musician. One of them, dressed in a velvet suit, draws pictures with a stick of charcoal, seven different ones in succession, now and then pausing to blow the charcoal dust from the paper before him. He is called the Draughtsman.

The other lad, also in velvet, sits before a small writing pad. He dips a real quill pen into real ink and writes a short sentence of up to 40 characters on the tablet before him. It can be any sentence of 40 characters, depending on how you set up the tabs that control the cams that move the pen. He is the Writer.

The reason so much is known about the Jacquet-Droz automata is that they survive, and they still work! They are the treasured trio of the Museum of Art and History in Neuchâtel; they sit quietly in their own special room under the inquiring eyes of daily tourists, and once a month, at three different times in the afternoon, they play their partitas, draw their charcoal sketches, and pen their French phrases.

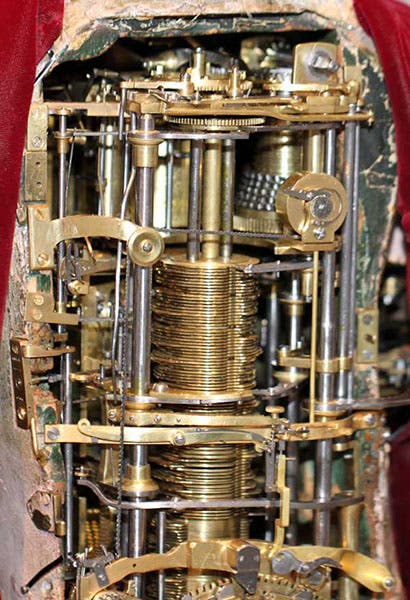

The Writer gets the most attention from commentators, for he has a set of input tabs that one can set to get him to write any particular phrase. He is, in a word, programmable, and therefore a good candidate for an early computer, perhaps the first computer. Remove the shirt from his back and gaze upon his brass innards, especially if they are in motion, and you will not doubt that this is a machine of amazing complexity and beauty, and it is hard to believe that it was designed and crafted by a Swiss clockmaker and his two assistants, using only a jeweler’s saw, a drill, a lathe, files, and a few other hand- or foot-powered tools. There are many videos available of the Jacquet-Droz automata in action. I like this one, narrated by an outstanding historian of science, Simon Schaffer.

You might recall that we once wrote a post on an automaton similar to the Writer. Crafted by Henri Maillardet about 25 years after the Writer, it is also still operational, and is in the possession of the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. It was the inspiration for the automaton in the film Hugo (2011). It too is an amazing piece of craftsmanship, but most of the operating mechanism that drives the boy hides inside the writing desk. With Jacquet-Droz’s Writer, all of the gears, cams, and cam followers are inside the boy’s body. This makes him not only an automaton, but an android – a machine in the form of a human. It may be the most awesome android ever built.

I have not seen the Neuchâtel automata in action, but Jessica Rifkin has. Professor Rifkin literally wrote the book on Enlightenment automata, and she recalled, in The Restless Clock (2016), that what she found most unnerving about the experience came before the performance, and involved the Musician. The automaton just sat there while the curator explained what was about to happen, but she was breathing, her breast slowly rising and falling as she waited her turn. That would be unsettling, and provides further indication that Jaquet-Droz was probing the limits of the difference between living beings and machines when he designed and built his androids.

If anyone else visits Neuchâtel before I do, please send photos. And if you find the grave of Pierre Jacquet-Droz, please leave a small wreath on my behalf. An artificial wreath with an aroma of lilacs might be most appropriate.

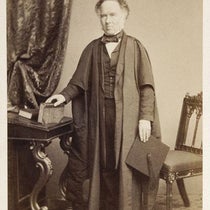

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.