Scientist of the Day - Pietro Bembo

Pietro Bembo, an Italian writer and cleric of the late Renaissance, was born May 20, 1470. He is best remembered for playing a major role in transforming the Tuscan tongue spoken in Florence into a respected literary language, which eventually became the Italian language of today. Bembo was also important is calling attention to the works of Francesco Petrarch, the 14th-century scholar who had to be revived several times before becoming established as the first Italian humanist. There are several other feathers in Bembo's cardinal's hat, not the least of which was having an affair with Lucrezia Borgia and living to tell (or not tell) about it, but we are going to pass over all of this to get directly to the one act, an archaeological act, that justifies his inclusion in a series on scientists. This was his acquisition of what is still known as the Bembine Tablet.

The Bembine Tablet, or Bembine Table, is a physical object, made of bronze and covered in enamel, ornamented by silver wire and inlay, and carved. It appears to be Egyptian, since it is covered with hieroglyphs – even the edges of the tablet are decorated with a procession of hieroglyphic figures. We show a detail of the actual tablet as our first image; you can see an engraving of the entire tablet surface here. The tablet has no known prehistory before 1527, when it was liberated from its original and unknown owner during the sack of Rome, and was subsequently acquired by Bembo. When he died in 1547, the tablet passed to the Gonzaga family of Mantua. In 1630, they lost it to Emperor Ferdinand II when he seized the city, and it then passed from owner to owner (unknown) until Napoleon's troops removed it from Italy in 1797. When Napoleon fell, the tablet returned to Italy, and ended up in the Egyptian Museum (Museo Egizio) of Turin, where it is still on display.

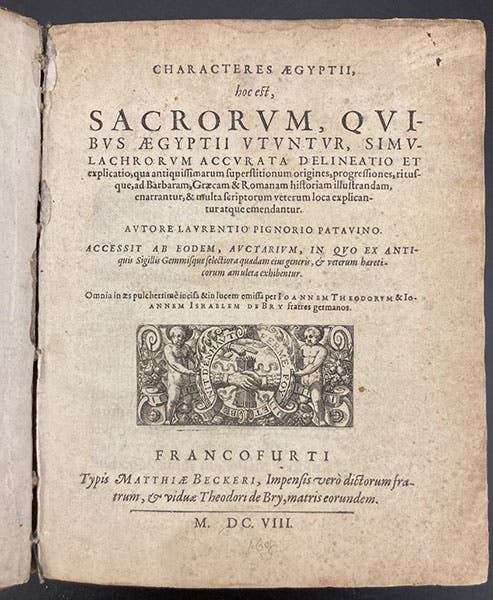

Title page, Characteres Aegyptii, by Lorenzo Pignoria, 1608 (author’s collection)

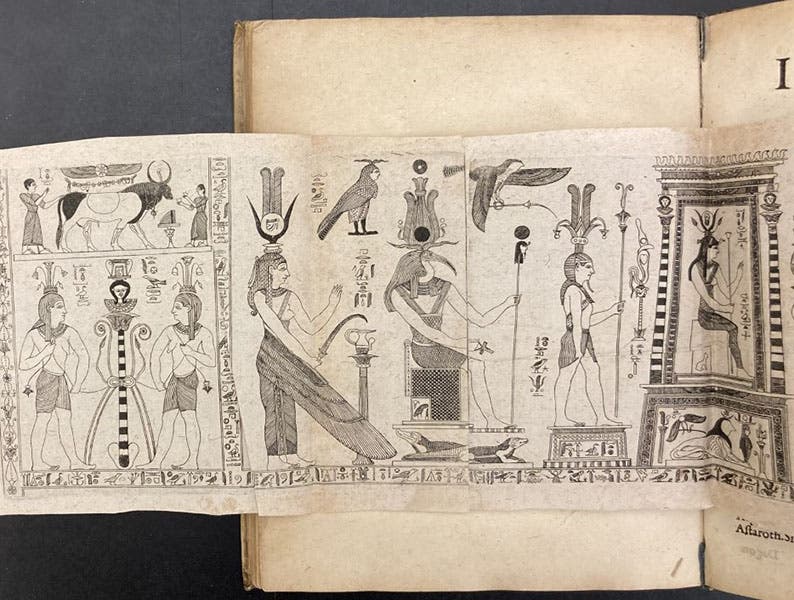

The first appearance of the Bembine Tablet in print was in a book by the scholar Lorenzo Pignoria in 1605, titled (translating from the Latin) On the Most Ancient Bronze Tablet of the Sacred Rites of the Egyptians. I have never seen a copy; I presume it was illustrated, but I do not know how, or how well. But the book was republished in 1608 with a new title, Characteres Aegyptii ... accurata delineatio et explicatio (Egyptian Characters … Accurately Delineated and Explained). I just happen to own a copy of this book, one of my few personal rare books, because when it came on the market in the 1980s, I was unable to persuade the Library that it was in scope for their collections (and it really wasn’t), so I acquired it myself. It was illustrated by the de Bry brothers of Frankfurt, sons of the master engraver Theodor de Bry, and superb engravers themselves. Two engravings show details of the top surface of the tablet; we see one of those here (fourth image).

Detail of part of the surface of the Bembine Tablet, engraving by Johann Theodor and Johann Israel de Bry, in Characteres Aegyptii, by Lorenzo Pignoria, 1608 (author’s collection)

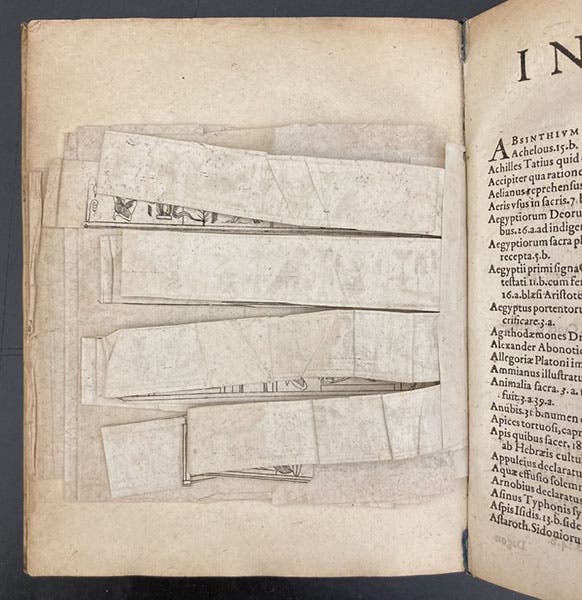

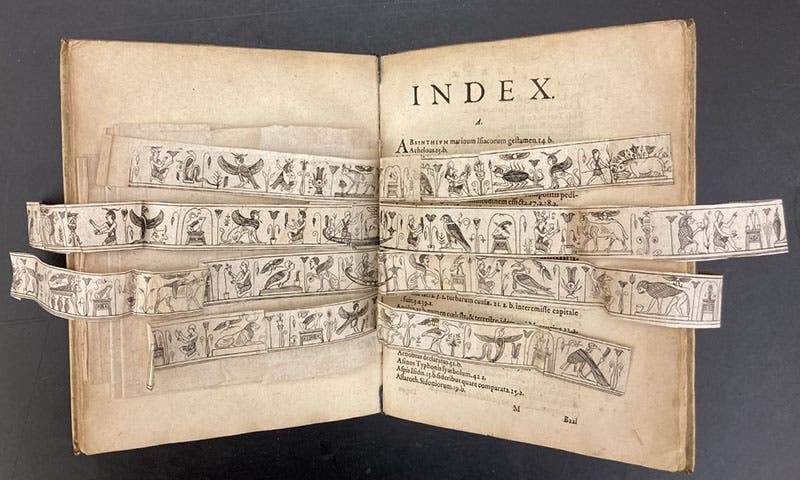

The four tablet edges were also illustrated, in a most intriguing manner. Each of the edges was depicted on a long strip of paper, made up of shorter engraved strips glued together. Then each pieced-together strip was carefully folded and glued in the center to a stub in the gutter of the binding. There were four of these, two longer and two shorter, lined up one below another. It must have taken hours of assembly to put together and mount the edge engravings for just one copy of the book, much less several hundred copies. When I first opened my copy to behold the four sets of folded strips, meticulously mounted and folded, I instantly fell in love with it, and I have never regretted its purchase, even though this is the first time I have ever discussed it in print or reproduced the engravings. We see here the edge engravings folded up (fifth image), and (as best I could manage), unfolded (sixth image).

Four engraved strips of paper, depicting the four edges of the Bembine Tablet, neatly folded, in Characteres Aegyptii, by Lorenzo Pignoria, 1608 (author’s collection)

The four engraved strips depicting the edges of the Bembine Tablet, unfolded, in Characteres Aegyptii, by Lorenzo Pignoria, 1608 (author’s collection)

Pignoria suspected that, although the figures were Egyptian, they did not depict actual Egyptian rituals, and he was right, although it took several more centuries for that to be appreciated. Modern consensus is that the tablet was made in Roman times, in the first century C.E., during a period when the cult of Isis was very popular in Rome. And it was made by craftspeople who could not read hieroglyphics. Many scholars, such as Athanasius Kircher, tried to decipher hieroglyphics using the Bembine Tablet as an aide, but it was futile, since the symbols do not mean anything. But as a first-century Roman artifact, beautifully fashioned of enamel and silver and delicately carved, it is an archaeological treasure, and worthy of as much attention as its much more famous Roman contemporary, the Portland vase in the British Museum.

Well, as you have no doubt realized by now, this is not really a post about Bembo, but about a beautifully crafted book. But that’s okay. Pignoria’s book is about Bembo’s Tablet, and I suspect Bembo would be fine with being remembered for preserving for the world one of the finest art objects of ancient Rome.

We have a printed portrait of Bembo in our collections, in the portrait book of Boissard (1597-99), illustrated, as it happens, by Theodor de Bry. But we could hardly use that when there is a glorious alternative, a painted portrait by the great Titian, with Bembo clad in his bright-red cardinal’s garb. The portrait, showing Bembo at age 70, is in the National Gallery of Art at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.