Scientist of the Day - Reginald John Farrer

Reginald John Farrer, an English traveler and plant collector, died Oct. 17, 1920, at the age of 40. Farrer was born in London, but the Farrer family had long owned an extensive estate in the village of Clapham, North Yorkshire, in the shadow of Ingleborough mountain, in what is called the Dales. Even as a boy, Farrer wandered these hills and collected and observed the alpine plants growing there in the limestone. He attended Oxford, met others with botanical interests, and soon was off to the Alps, where he observed the original alpine plants, sketched them, and brought them back to see if they would thrive in the Yorkshire hills. He cultivated a rock garden on the grounds of the family estate, called Ingleborough Hall. Rock gardens had long been popular in Victorian England, but they tended to be contrived, which is to say, not intended to be natural looking, but rather showy, with great emphasis on large masses of flowers that changed color as you went from plot to plot. Having been to Japan on one of his first trips to the East, Farrer envisioned a garden as a natural rock setting, with the plants poking out here and there, as they did in nature, or in a Japanese garden.

Farrer also liked to write, and he produced 19 books in the brief 20 years of active adult life allotted him. These were books on his travels, with occasional forays into fiction. Early on he wrote My Rock Garden (1907), which went through many editions and proved to be his most popular work. We do not have any editions of this work in our library, for some reason. In fact, we have only one of his books, but it is his most important one, and we will get to it shortly.

In 1914, Farrer embarked on his first extensive plant-gathering expedition, going to Tibet and the province of Kansu (Gansu) in northwest China. He not only collected seeds and herbarium specimens, but he drew and painted alpine plants in place, usually just sketching in the background, and concentrating his attention on the way the plant appeared in its rocky environment. Enough of these paintings survive, in London, Clapham, and Edinburgh, that one can pick and choose one’s favorites, and I chose a sketch of Meconopsis, the Himalayan blue poppy (first image), which happens to be at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh, along with 58 other Farrer sketches, and his portrait. You may scroll through thumbnails of their holdings here.

Farrer's writing takes some getting used to. He wrote, as someone described it, at the top of his voice, full of exclamations and opinions, especially about other rock gardeners who violated what he saw as the proper constraints for rock gardens. So he had as many enemies as fans when it came to garden landscaping. Some of his prose enthusiasm was no doubt a compensation for a birth defect, a cleft lip and palate. He covered the cleft lip with a bushy mustache, but he couldn't do much about his high raspy voice, so in personal interactions, he had a bit of an inferiority complex, a rarity, someone else remarked, for a Yorkshireman. But in his writings, his infirmity disappeared.

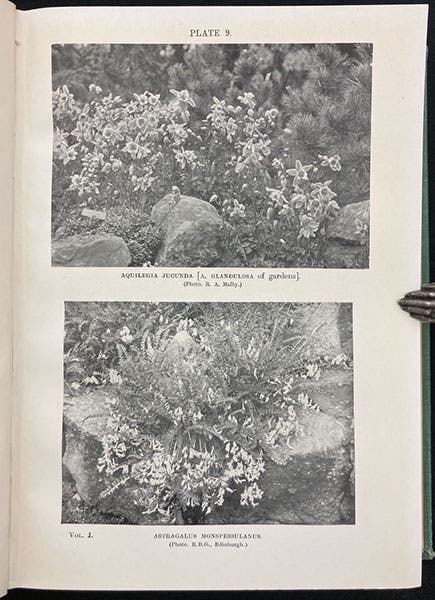

Just before World War I, Farrer completed his major work, a two-volume encyclopedia of rock garden plants, which he called The British Rock Garden. This is a completely different book from the similar sounding My Rock Garden. The publication of the book was delayed by the war, and it did not appear in print until 1919. We have this work in our collections. It is not heavily illustrated, but it does have a modest number of plates with black-and-white photographs of various rock-garden plants. We show here the title page (fifth image), and one of the plates, depicting Aquilegia (columbine) at the top, and Astragalus (vetch) below (sixth image).

While the book was awaiting publication, Farrer made his trip to China, which lasted 2 years (1914-15), and then, in 1919, still before the publication of The British Rock Garden, he headed off again on a trip to northern Burma. On both of his extensive trips, he had a traveling companion, William Purdom on the China trip, and E.H.M. (Euan Hillhouse Methven) Cox on the Burma trip. Cox later wrote a book about the Burma expedition, since Farr could not, having died on this day in 1920, alone in the mountains on the border with China, the cause of death unknown, although often speculated about.

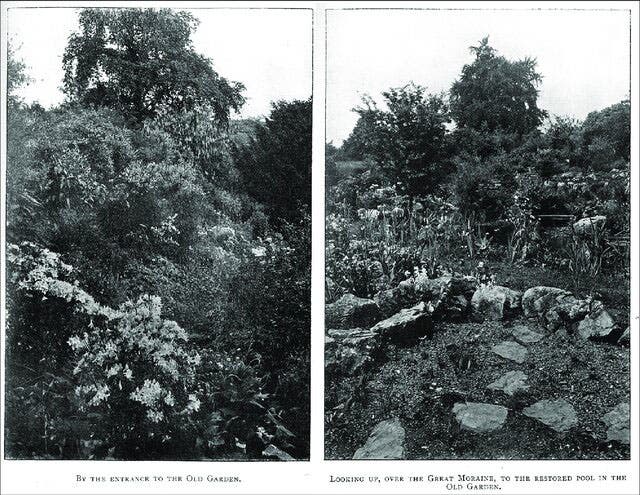

Ingleborough Hall is still there (third image), and so is Farrer’s rock garden. Apparently, there is some interest in restoring it, as a study of the present state of the garden was commissioned in 2016. That study is available online, and we have used two images from it here (third and fourth images). I don’t think the estate and garden are open to the public. But the surrounding hills are, where you can find many of the rhododendron species that Farrer brought back from China.

Many plant species are named after Farrer. We show you one, a lovely Viburnum that is native to China (seventh image). To see more, many more, just key “farreri” into the search box of Wikipedia, or click here, where I have done it for you.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.