Scientist of the Day - Richard Carrington

On Sep. 1, 1859, Charles Darwin wrote a letter to his best friend Joseph Hooker, complaining about his poor health and the onerous task in which he was engaged, correcting the proofs for the last two chapters of his Origin of Species, due to be published in November. Seventeen miles away, at Redhill in Surrey, the astronomer Richard Carrington was preparing to look for spots on the Sun. Carrington’s activities on this day would prove to me much more momentous than Darwin’s.

Carrington was born on May 26, 1826, in Chelsea. After attending Cambridge University, Carrington worked for a while as a professional astronomer at Durham, but he balked at the tedious duties required of that position, and having sufficient means of his own, he set up a private observatory at Redhill, in Surrey, in 1852. At first, he measured the positions of stars, publishing a catalogue of circumpolar stars in 1857 that went down to the 11th magnitude (1st magnitude stars are very bright, the smallest magnitude visible to the naked eyed is 6, so 11th magnitude stars are barely visible, even in a good-sized telescope). We have this publication in our collections. Its title page is the source for our opening woodcut of his observatory (first image).

Then Carrington turned his attention to sunspots. He discovered for himself that sunspot activity is cyclical, going from a minimum of spots to a maximum and back again, in about 11 years. Unbeknownst to Carrington, the 11-year sunspot cycle had already been discovered by two German astronomers, Samuel Schwabe and Rudolf Wolf. But Carrington also observed that sunspots change their latitude during the cycle; a cycle begins with a few spots located at 30 degrees north and south solar latitude, and then the spots slowly drift toward the equator as they increase in number, before the sunspots disappear and then resume at mid-latitude. This was a new discovery, beknownst to no one at the time.

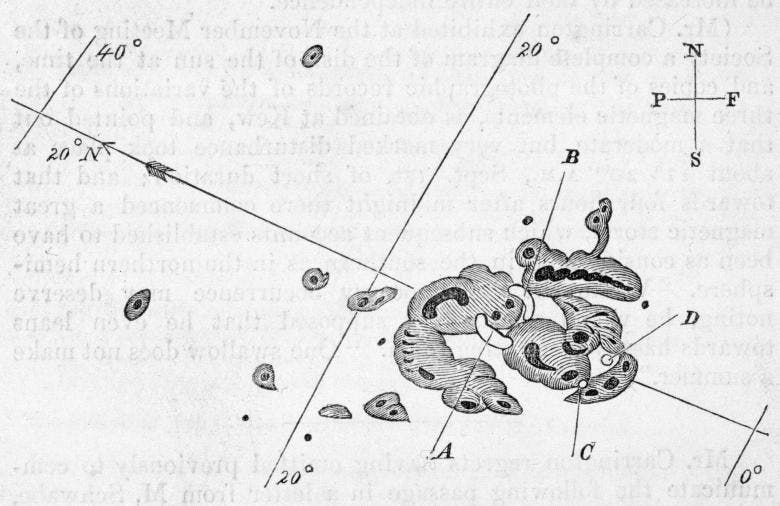

But Carrington is best known for a single observation he made just before noon on Sep. 1, 1859. While observing the Sun, he noticed a pair of intense white dots among the dark sunspots. He carefully made a map of the dots and spots. Within twelve hours of his observation, the earth was struck by what we now know was a severe magnetic storm. Auroras were incredibly intense, so much so that one Colorado resident claimed he could read the newspaper by its light. Telegraph operation became nearly impossible. One pair of operators in New England found they could communicate if they disconnected their batteries and used the electric current induced in the wires by the auroras. What Carrington had observed, and was the first to observe, was a solar flare. By the time his observation was published in October, he was ready to argue that the geomagnetic storm on Earth had been caused by the intense solar activity, the first time that it was realized that solar disturbances could directly affect the Earth. The event was also observed and communicated by another amateur, Richard Hodgson, who probably deserves more credit than he gets.

Our Library, for some reason, lacks the volume of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society that contains Carrington’s brief paper (and that of Hodgson), so we show you the diagram from another source (second image). It is often reproduced. If you can find the letters "A" and "B”, those are the solar flares – all the other markings are sunspots.

The solar storm of 1859 is now referred to as the "Carrington Event." The modern term for a flare of this type and magnitude is a coronal mass ejection (CME). Had the Carrington event occurred in modern times, it would have wreaked havoc on electrical grids and caused widespread power outages, and who knows what the effect would have been on data systems and the internet. We show here a photograph of a similar but less intense CME that occurred in August of 2012, which fortunately missed the Earth (third image).

Carrington published a book on his sunspot observations in 1863, and we have that volume in our collections as well. There is no known portrait of Carrington. His Wikipedia article used to include a portrait, but it turned out to be a portrait of William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, and it was removed (although it lingers on the many sites that crib from Wikipedia). No authentic portrait has been found to replace it.

Carrington died on Nov. 27, 1875, at age 49. He was buried in West Norwood Cemetery in Lambeth, Greater London. Findagrave.com has an entry on Carrington, but they do not include a photo of his gravestone, if there is one. But they do have the photo of Kelvin, masquerading as Carrington.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.