Scientist of the Day - Richard Kirwan

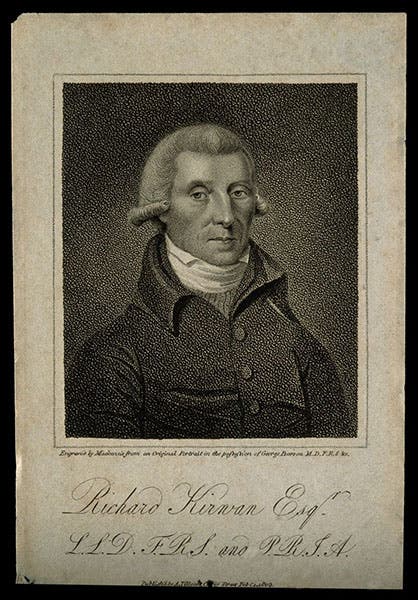

Richard Kirwan, an Irish chemist, mineralogist, and geologist, was born Aug. 1, 1733, in County Galway, Ireland. Chemistry was his first love as a student, but he had to go to France to study, as his family's Catholicism prevented his attending a British university. He returned to Ireland and studied for the bar, which required that he renounce his Catholic faith, and this time he did so. But he soon found himself the sole heir to the fortunes on both sides of the family, and that put an end to his legal career. He moved to London for a few years, and then again for ten years, where he established himself as one of the city's leading chemists and mineralogists, before returning to Ireland in 1787 to help establish the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin. He would publish most of his papers from 1790 on in the proceedings of the Academy, and become president of the Academy in 1799.

I find Kirwan to be a fascinating fellow. He took an active part in two of the leading scientific controversies of the 1780s and 90s: the attempt by Antoine Lavoisier and several other French chemists to replace the phlogiston theory of combustion with the oxygen theory, and the move by James Hutton and John Playfair to overthrow the reigning neptunism of geologists following Abraham Werner, with a new theory of geological process in which the Earth's internal heat and pressure played a much more important role. You might have noticed that these are developments in two different fields, yet Kirwan was a central figure in both. He had the dubious distinction of being on the wrong side in both controversies, yet he was the one that the proponents of Lavoisier, and of Hutton, feared the most, and spent the greatest time trying to refute. We cannot deal with both developments in one post, so we will focus today on Kirwan's defense of the phlogiston theory, and on a later occasion, we will tackle his opposition to Hutton's plutonism.

The phlogiston theory, which went back to the late 17th century, was an attempt to explain what happens when substances burn or form oxides (calcination). Phlogiston was a proposed substance that was given off when an object burned, or when something calcinated (rusted). The phlogiston given off during combustion had to be absorbed by the air, so when the air was saturated with phlogiston, it would no longer support combustion. The phlogiston theory was very useful and accounted for many new phenomena; when nitrogen, which does not support combustion, was discovered in 1772, it was identified as phlogisticated air, whereas oxygen, discovered in 1774, which supported combustion in spades, was dephlogisticated air. Hydrogen gas was thought by Kirwan to be phlogiston itself, since it was highly combustible.

Antoine Lavoisier and his cohorts offered up a new theory of combustion in the 1780s, derived from the discovery of oxygen by Joseph Priestley and others. The oxygen theory of combustion proposed that substances burn or calcinate when they combine with oxygen; combustion is not the release of a substance, phlogiston, but the taking up of an element, oxygen. This explained a recent discovery, that hydrogen burns in oxygen to form water. It also explained why elements gain weight during calcination – they were taking on oxygen; if they were giving off phlogiston, then the weight gain was a problem.

Kirwan thought he could save the phlogiston theory by arguing that, at lower temperatures, oxygen and hydrogen (phlogiston for Kirwan) combined to form fixed air (carbon dioxide), which was absorbed by many substances, producing the weight gain. He said so in a book, An Essay on Phlogiston, and the Constitution of Acids, published in London in 1787. Lavoisier and his colleagues, Claude-Louis Berthollet, Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau, and others, evidently considered this a serious assault on their new chemistry, and the book was immediately translated into French by none other than Marie-Anne Pierette Paulze, Madame Lavoisier, who solicited responsive notes from her husband and his collaborators, which were published along with Kirwan’s translated text in 1788. We have both Kirwan’s original book and the French translation in our collections; neither book is illustrated, so we show here the title page of the French translation and a few pages of the notes by Lavoisier and Berthollet.

Almost the best part of the story is that the French translation was then translated back into English, with all of the notes of the French chemists, in 1789. Kirwan had no part in this – he was now back in Dublin. The translator and editor was William Nicholson, who would later achieve prominence as the founder and editor of the first British chemical journal, Nicholson’s Journal, in 1797. We do not have the 1789 “new edition” of Kirwan’s An Essay on Phlogiston; it would be a nice future acquisition.

Interestingly, Kirwan abandoned the phlogiston theory in 1791, after he was unable to create fixed air (carbon dioxide) from hydrogen and oxygen. That hardly ever happens, where a scientist of age 58 gives up on a theory that he has defended for 20 years, and it draws from us a nod of respect. Kirwan then turned his attention to Hutton’s plutonism, which first appeared in a paper published in 1788. Kirwan would lash out at Hutton’s theory with fervor, and that will be the topic of our next episode in the scientific life of Richard Kirwan.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Antoine Lavoisier’s comments on Richard Kirwan’s chapter on the decomposition and composition of water, Essai sur le phlogistique, et sur la constitution des acides, by Richard Kirwan, [trans. by Madame Lavoisier], 1788 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/936291bd-b854-4aff-aee6-d50d4dfe9e47/kirwan1.jpg?w=534&h=582&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Antoine Lavoisier’s comments on Richard Kirwan’s chapter on the decomposition and composition of water, Essai sur le phlogistique, et sur la constitution des acides, by Richard Kirwan, [trans. by Madame Lavoisier], 1788 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1052059c-9d0e-43ae-b079-9886a7e04742/kirwan1.jpg?w=667&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Title page, Essai sur le phlogistique, et sur la constitution des acides, by Richard Kirwan, [trans. by Madame Lavoisier], 1788 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/c0baa84f-ecc7-4144-bf76-98d81d384a53/kirwan3.jpg?w=391&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Claude-Louis Berthollet’s comments on Kirwan’s chapter on nitric acid, Essai sur le phlogistique, et sur la constitution des acides, by Richard Kirwan, [trans. by Madame Lavoisier], 1788 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/acaaa463-b1af-40f9-8ce9-5cca2c28c472/kirwan4.jpg?w=397&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)